Sexplosion: From Andy Warhol to A Clockwork Orange – How A Generation of Pop Rebels Broke All The Taboos by Robert Hofler

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It all seems a long, long time ago. To anyone under the age of, say, 45, this book may well feel like a dispatch – albeit a fiercely entertaining one – from another solar system. Time rolls on, values evolve. When Ken Russell died in 2011, news bulletins struggled to explain why a scene of two men wrestling in the nude in Women In Love had once seemed like the end of civilisation as we know it.

As befits a senior editor of Variety, Robert Hofler’s focus in Sexplosion: From Andy Warhol To A Clockwork Orange – How A Generation Of Pop Rebels Broke All The Taboos is very much on Hollywood and the smart end of Manhattan, but his chronicle of the cultural watershed of the late Sixties and early Seventies does acknowledge the contribution of the Brits. One of the supporting players is John Trevelyan, Secretary of what was then known as the British Board of Film Censors. A schoolmasterly character, he clearly revelled in his role as tastemaker-in-chief. (Here’s a question for the reader. Can you name his equivalent in today’s British Board of Film Classification? No, I thought not. How the mighty are fallen.) Was Trevelyan a sinister hypocrite, as one director claimed? Or did he work wonders, as the late Russell argued, in getting his colleagues to approve as much controversial material as possible? The latter seems much more plausible, but Hofler leaves readers to make up their own mind.

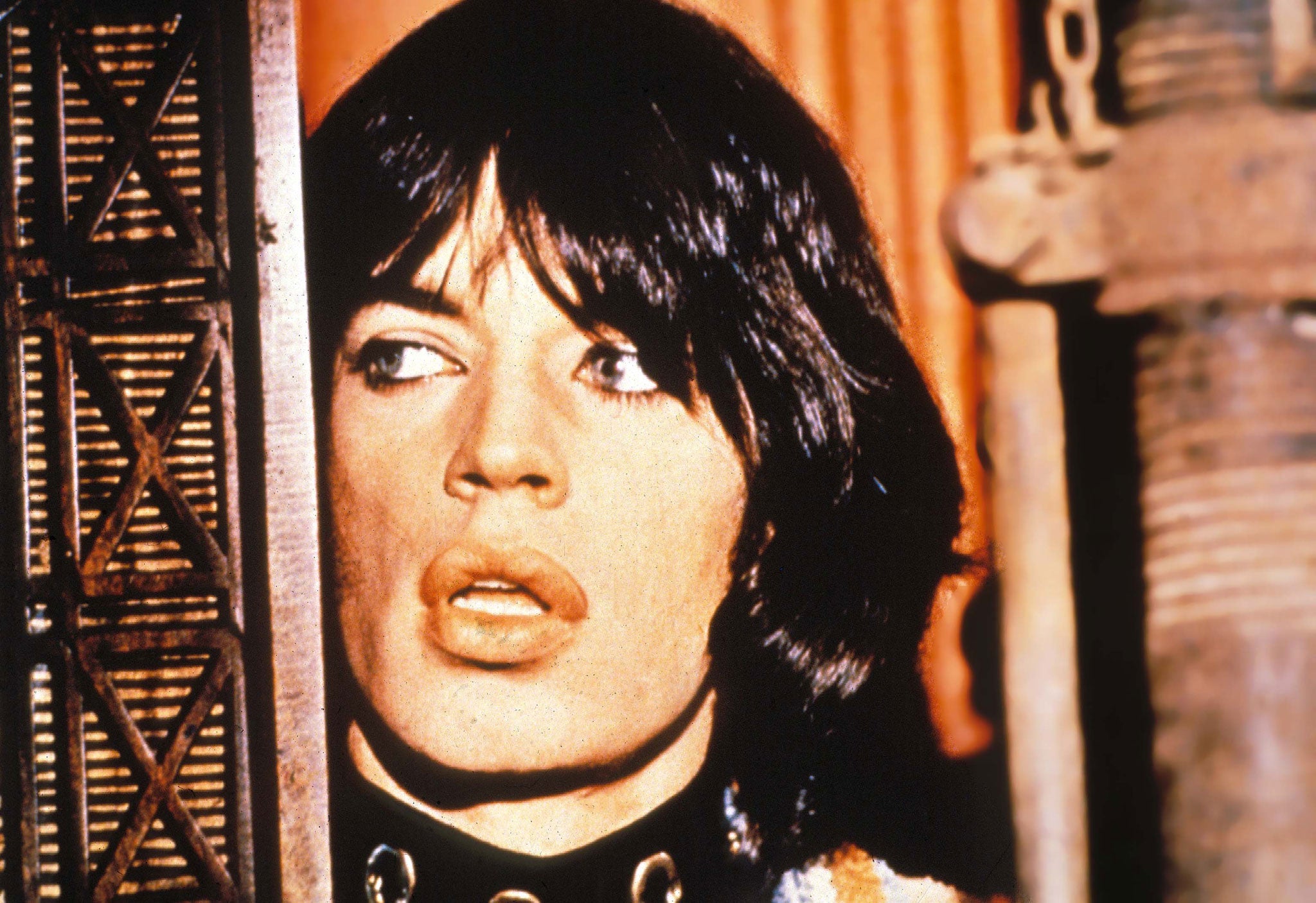

Mick Jagger had a walk-on part too as a participant in that cult film-cum-happening Performance, not to mention the sorry spectacle that was Altamont, the West Coast’s answer to Woodstock which, thanks to the Stones’ hubris, ended in death and mayhem. It’s one thing to toy with nihilism on celluloid; real life tends to be messier. Hofler is clearly on the side of the anti-censorship forces. (You can’t help wincing when he notes that, not long before Midnight Cowboy was made, the Supreme Court had ruled “that homosexuals were indeed ‘psychopathic.’” But he is alive to the inevitable truth that cultural liberation unleashed its share of poseurs and charlatans. Something of that view is articulated by John Updike, who conquered the best-seller lists with Couples, but wondered aloud about the wisdom of turning sex into a form of religion. And Hofler is in no doubt that, at least at first, it was men rather than women who stood to gain most from all the iconoclasm.

But the moralising is done with the lightest of touches. Like Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, Peter Biskind’s study of the New Hollywood, Sexplosion deftly weaves a path through the friendships and collaborations which created common ground between the nude stage revue Oh Calcutta!, Philip Roth’s novel about masturbation, Portnoy’s Complaint, and Gore Vidal’s transsexual extravaganza, Myra Breckinridge. Above all, he amasses one unforgettable vignette after another. Jackie Onassis and her husband roll up in separate cars to watch the sexually explicit Swedish film I Am Curious (Yellow). Marlon Brando frets about his shrivelling manhood on the set of Last Tango in Paris. Princess Margaret, worse the wear for gin, is horrified by the film about a free-spirited bisexual, Sunday Bloody Sunday: “Men in bed kissing!” Hofler captures an era in all its demented glory.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments