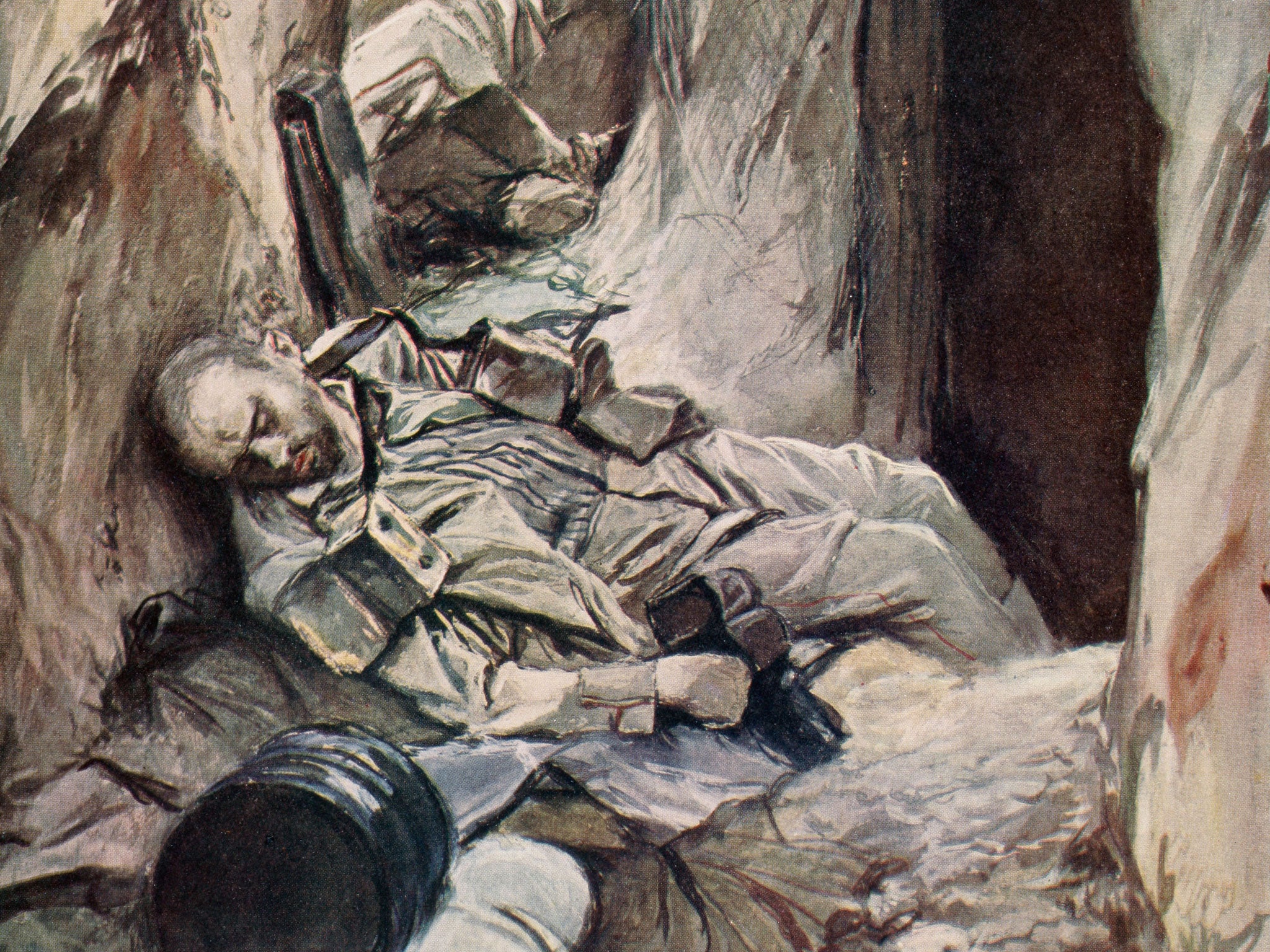

Schlump by Hans Herbert Grimm, book review

The Nazis burned copies of this great anti-war novel, but the manuscript survived through a remarkable act of subterfuge

When German schoolmaster Hans Herbert Grimm's semi-autobiographical novel about the First World War was published anonymously in 1928, it was overshadowed by the success of Erich Maria Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front.

Now, a century after the Great War, Schlump reappears in Jamie Bulloch's excellent new translation and the extraordinary story of its rediscovery probably warrants a novel of its own. Grimm, Volker Weidermann explains in his afterword, concealed his manuscript inside a wall in his home after the Nazis burned copies of Schlump, which they considered "un-German", in 1933. It wasn't found until 2013 when Grimm was finally established as its author.

In 1915, Emil Schulz, a young German who's given the nickname "Schlump" by a policeman, is 17 when, full of visions of heroism, he defies his parents and volunteers for military service. He's charming, attracting girls at home and in occupied France, and pugnacious, hurling a plate at a cavalryman who's contemptuous of his volunteer status, which sparks a mass brawl and leaves the cavalryman with "hot sauerkraut … burning his face and running down his neck."

Initially, Schlump loathes the "joyless farms," "women with black moustaches" and "appalling dialect" of rural France. However, he grows fond of Loffrande, the village where he's billeted, and the "Frenchies" warm to him. "The gruesome melody that droned from the front" can be heard in the distance but, otherwise, Loffrande is idyllic. Villagers get around rationing to cook hearty stews, drink merrily, and soon Schlump has "almost forgotten that he was a soldier".

For a while, Schlump's days of chasing girls, cadging cigarettes and thumbing his nose at fogeyish superiors reads like an unexpectedly successful mix of Kingsley Amis's comic bite and Joseph Roth's Germanic intensity. The latter characteristic comes from the moral vision, which powers Grimm's prose, and the certainty that fate will soon deliver Schlump to somewhere hostile. "Only the fools end up in the trenches, or those who've been in trouble," an officer tells Schlump and yet that's where he's sent.

Humour never disappears from these pages – Schlump consistently "laughed out amidst this hellish turmoil" – and the image which has been making me giggle for days concerns Schlump's bafflement at the way his comrade, Lemke, reacts to coming under fire: "With the same regularity as the machine gun, a serious looking Lemke bowed towards the French, as if trying to introduce himself to the enemy." Schlump simply doesn't realise that Lemke is ducking bullets.

The hell of front-line service is more impactful for the tranquillity that preceded it and the immediacy with which it obliterates Schlump's naivety. An exploding shell "hissed through the air like a thousand cats, some wailing and howling like cursed souls".

Hearing plays a significant part in reading Grimm because, like a poet, he encourages us to listen with our eyes and uses onomatopoeias effectively: "Tak-tak-tak-tak," go the machine guns, while shells "whee-ee" through the air as hot pieces of shrapnel buffet the wet mud ("pff, pff, pff"), and bullets "feeow" about Schlump's ears.

Schlump rarely gets more than two hours sleep, at most he eats one meal a day and, when he does rest, rats crawl over his chest. War is "thrilling and deadening at the same time," but the dirt, boredom and deprivation pale in comparison to the indelible horrors of battle: an infantryman, trapped in barbed wire during shelling, screams "Mother! Mother!", while another is left with his skull lying beside him ("death had neatly placed his brain on top").

Schlump becomes a shrewd observer of the injustices of military hierarchy and a veteran of the Somme crystallises the hypocrisy of generals who orchestrate manoeuvres far from the front: "If we avoid being blown to bits they let us die of hunger."

Twice Schlump is hospitalised and, while recuperating, he registers the domestic impact of the war. Germans are starving, families are torn asunder and Schlump's father, a tailor all his life, must work in a factory because there's "no man in the land who wanted a suit".

Weidermann calls Grimm's novel a "docu-fable" and Schlump's exposure to other peoples' suffering shapes his metaphorical journey from youth to maturity, innocence to experience, romance to realism.

On my first reading, I thought Grimm's set-pieces, where soldiers recount their experiences to Schlump in monologues disguised as dialogue, read like reportage. However, I now see these scenes as fables within the novel's grander fable, a device which lets Grimm expand and contract the focus of his clear, documentarian's lens to capture personal responses to world events.

I remain sceptical of Grimm's depictions of women: any woman aged over about 30 is liable to have a face like "old camembert" or eyes "black as a stove door", while young beauties are idealised and some are infantilised with small breasts and described affectionately as "little".

But Schlump himself is very young, a detail which can be forgotten amid the long war at the heart of this fairly short novel. By the time Germany eventually loses the war, Schlump's faith in humanity and his capacity for love have grown. There's even an indication that one of his flings will endure.

Peace, however, won't last and again I'm reminded of Joseph Roth who said that in 1918 defeated veterans came "home from a small battlefield to a great one". So it proved and, in the 1930s, Grimm joined the Nazi Party because he was, according to his publisher, "anxious to preserve the anonymity of his authorship".

Weidermann also attributes this move to Grimm's desire to preserve his middle-class life in "his beloved Altenburg". Was there another way? It's difficult to know without being in Grimm's impossible position (although one likes to think one would have acted differently) but the post-war communist government of East Germany was unforgiving and banned him from teaching. In 1950, shortly after a meeting with GDR officials, Grimm committed suicide.

Should we be put off reading Schlump by Grimm's affiliation with the Nazis? Roth, a Jew who served in the First World War and went on to write blistering denunciations of National Socialism, might well say, "Yes". However, could WH Auden's idea, that time pardons poets with problematic views "for writing well", apply to Grimm? After all, time, translation and the consecutive tragedies of the German 20th-century are what this exceptional work has travelled through to reach us.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks