Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari, book review: Eloquent history of what makes us human

Welcome wit warms this treatise on human development

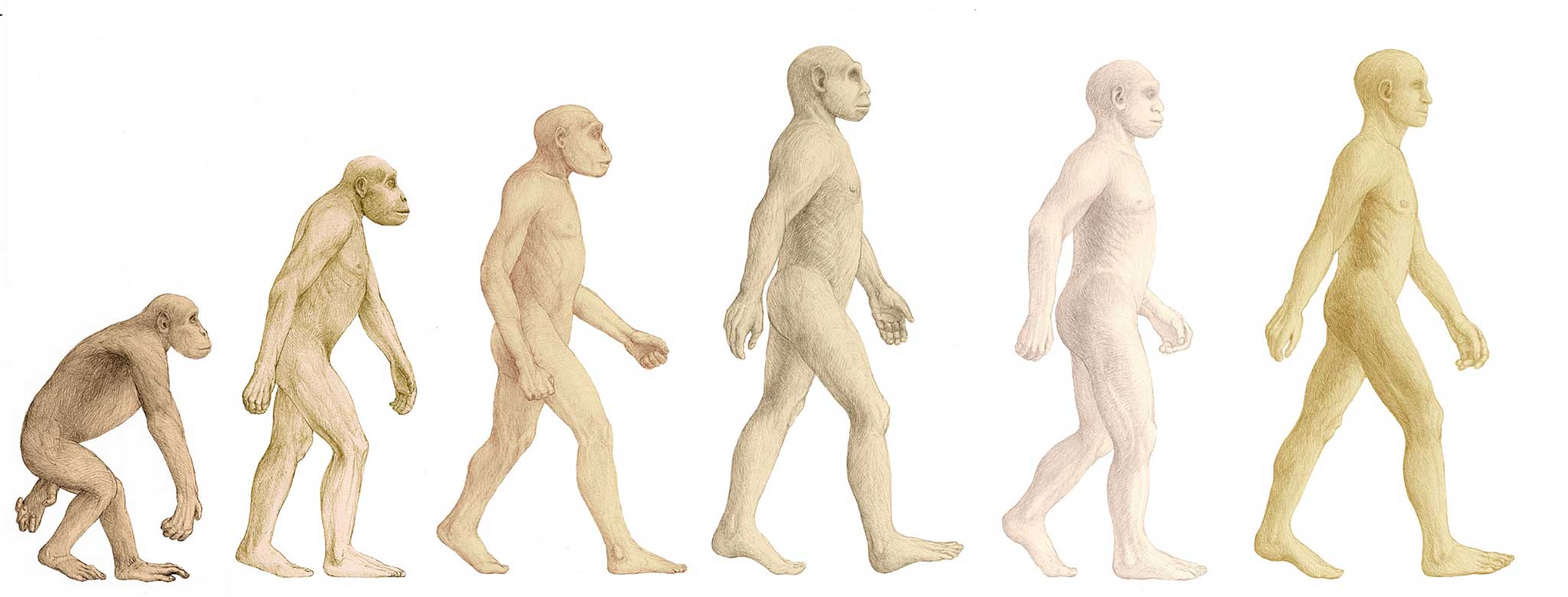

It is an impediment to understanding the human story that the innovations that made us human – a long list including the control of fire, articulate language, the development of agriculture and herding, the working of metals, glass and other materials, abstract reasoning – took place over periods out of kilter with the time span of human generations.

Each generation saw itself as living a similar life to its predecessors, with the occasional addition of a slightly better way of accomplishing one thing or another. The true course of events is only now being uncovered by the sophisticated forensic techniques developed by science, not least the sequencing of ancient DNA and the mapping of human migrations through the DNA profiles of people living today.

As a historian, Yuval Harari (who teaches at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem) belongs to the school founded by Jared Diamond (who endorses the book on the cover), in applying scientific research to every aspect of human history, not just the parts for which no written accounts exist. In truth, Harari uses less science than Diamond. He emphasizes the difficulty of knowing in detail the lives of our remote forebears and is often content to say – of topics that are being urgently investigated by the more forensically inclined – "frankly, we don't know". His ideas are mostly not new, being derived from Diamond, but he has a very trenchant way of putting them over.

Typical is a bravura passage on the domestication of wheat, in which he floats the conceit that wheat domesticated us. What was once an undistinguished grass in a small part of the Middle East now covers a global area eight times the size of England. Humans have to slave to serve the wheat god: " Wheat didn't like rocks and pebbles, so Sapiens broke their backs clearing fields. Wheat didn't like sharing its space..." and so on.

Harari proposes three big revolutions around which his story revolves: the Cognitive Revolution of around 70,000 years ago (articulate language); the Agricultural Revolution of 10,000 years ago; and the Scientific Revolution of 500 years ago. The last is part of history, the second is increasingly well understood, but the first is still shrouded in a mystery that DNA research will probably one day clear up.

Although the book is billed as a short history, it is just as much a philosophical meditation on the human condition. One great overriding argument runs through it: that all human culture is an invention. The rules of football; the concept of a limited liability company; the laws relating to property and marriage; the character, actions and notional edicts of deities – all are examples of what Harari calls Imagined Order. He develops this idea into a magnificent, humane polemic, particularly highlighting the sorrows that accrue from society's justification of its cruel practices as either natural or ordained by God (they are neither).

Not only is Harari eloquent and humane, he is often wonderfully, mordantly funny. Much of what we take to be inherent cultural traditions are of recent adoption: "William Tell never tasted chocolate, and Buddha never spiced up his food with chilli".

Towards the end of the book, the influence of thinkers other than Diamond emerges. He rehearses Steven Pinker's argument that objectively (to judge by mortality statistics) the world is, despite appearances, becoming less violent; passages on individual happiness and how it can be assessed alongside more conventional historical topics smack of Theodore Zeldin, both in style and content.

Inevitably, in a "big picture" account such as this, some portions of the canvas are less hatched in than others. For this reader, these later sections seemed weaker, but in the last chapter the brio returns as Harari considers what humankind – who developed culture to escape the constraints of biology – will became now that it is also a biological creator. Sapiens is a brave and bracing look at a species that is mostly in denial about the long road to now and the crossroads it is rapidly approaching.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks