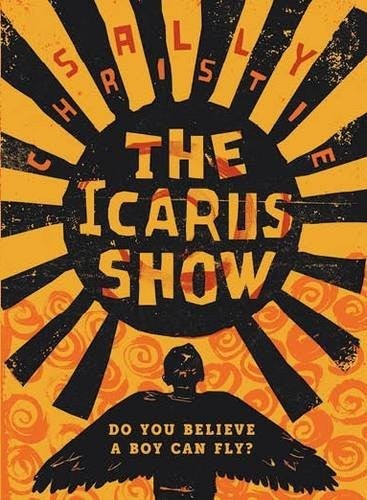

Sally Christie, The Icarus Show: 'How to tackle bullies? You could just rise above them', book review

Set in a modern comprehensive school, its main character Alex Meadows has long decided that the safest way to get by is to be a non-reactor

Bullies in traditional school stories commonly ruled through inflicting physical pain, thereby honing techniques that might come in useful for those who are later recruited into the Colonial Police Service. Today, if modern children’s stories are to be believed, bullies operate more in the psychological sphere.

Their favourite game is to play on fellow-pupils’ dread of being forced into publicly losing their cool. Such is the case in Sally Christie’s pulverising The Icarus Show, her first novel for 20 years and all the more welcome for that.

It is set in a modern comprehensive school, and its main character Alex Meadows has long decided that the safest way to get by is to be a non-reactor. After all, “Reactors get hurt. The ultimate example of a non-reactor was a stone. If you kicked a stone, it ended up just the same, only further down the road.”

This policy ensures that he passively accepts any insults coming his way and is always ready to curry possible favour from Alan Tydman, the school bully. Spending time with such a determinedly unheroic character could have its problems for readers, but contrast is provided by new boy David Marsh.

Like Christopher, the equally mysterious school newcomer in Michael Morpurgo’s novel The War of Jenkins’ Ear, David is a free spirit and aims to stay that way. But standing up to Tydman and his gang of enforcers only gains him pariah status. Alex, who lives next door to him, also avoids any contact lest it prove socially contagious.

Yet David, or “Bogsy” as he has now been christened, has his own way of fighting back. Unsigned notes accompanied by feathers start appearing in pupils’ bags. The bullies, previously in general control of everything going on outside the classroom, come to feel uneasily disoriented while never quite losing their long-standing power. The otherwise silent David is also hard at work on a secret project in the garden shed that abuts on to Alex’s own place of refuge. Unable to stop himself, Alex determines to find out what’s going on.

He is helped by his best and only friend Maisie, an elderly lady who used to live next door but has now been relocated to a care home. She senses that something dangerous might be about to happen and urges Alex towards greater understanding. Gradually the two boys, both outcasts in their own eyes, become closer.

But Alex still remains guiltily in thrall to the school tormentors, and when his new friend’s project is partially revealed he can only watch the bullies taking their brutal vengeance. Driven to desperation, David makes his last move. Will a modern-day Icarus fare any better than his ancient Greek counterpart? Read this fine novel and find out.

Christie is the daughter of Philippa Pearce, whose novel Tom’s Midnight Garden is an uncontested classic in children’s literature. Like her mother, she writes beautifully, making the most out of short sentences and plain language. Her 264 pages here are ample to achieve what she sets out to do at a time when sprawling lengths and lax editing have become something of a pattern in other children’s and young adult fiction. Christie also avoids retreating into fantasy or historicism, preferring instead to focus on the here and now.

The picture she provides is not complete. Parents remain puzzlingly off-stage and there is barely any mention of that other digital world inhabited by today’s children. But this also means that her story runs less risk of quickly dating as modern technology continues to re-invent itself on a yearly, if not monthly, basis.

Any television programme that focused on episodes of bullying leading to the possibility of a suicide attempt would these days always be followed by a list of contact points for viewers who might have felt affected by what they had just seen and would like further advice.

Children’s publishers should surely start thinking about providing something similar with contemporary novels for young people that also focus on serious personal problems. A genuinely happy school story or rite of passage novel is now rare indeed, and if present trends continue there will be many more tales describing different types of misery in the years to come.

Young readers reportedly seem to relish this sort of fiction but there should also be more consideration of how some of them may have been reacting to a troubling text at the time or afterwards.

Useful addresses or phone numbers could easily be included at the end of any book before it is time to move on, possibly leaving some important questions still unanswered. So come on David Fickling and your mates in children’s publishing – why not get your act together along these lines for the future?

The Icarus Show, by Sally Christie. David Fickling £12.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks