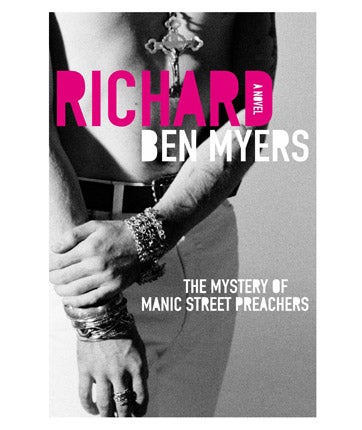

Richard, By Ben Myers

A curiously blunt stab at a rock icon

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It's now 15 years since Richey Edwards, lyricist, "Minister for Propaganda" and non-functioning guitarist for Manic Street Preachers, disappeared from the Embassy Hotel in London on the morning he was supposed to leave for America to promote the band's third album, The Holy Bible.

His presumed suicide (his car was found near the Severn Bridge, a notorious suicide spot) cemented a cult status already blossoming thanks to Edwards' outré look, punk attitude and personal problems. He suffered from anorexia, and self-harmed, and spoke frankly about these subjects.

Ben Myers's novelisation of his life starts in the hotel, and then moves in two contrary directions: first, down to the car park and out on that last journey home to Wales, but also right back to his childhood, in Blackwood, outside Cardiff. From there Myers runs through Edwards's and the band's career. The shift between the two sections gives the book a certain propulsion, but there's no escaping the fact that the writing is, considering its subject, bizarrely insipid.

Obviously, there are dangers in representing a human mind set on suicide, but Myers plays it far too safe, retreating to angsty clichés ("It feels like a thousand Sundays have been distilled down into archetypal Sunday; lonely, listless and oppressive. No hope for tomorrow. No sun in the sky.") He provides Edwards with an italicised alter ego to goad him onto self-destruction, but their dialogue is far from convincing. "Go on, then. Stop all this bullshit attention-seeking and prove it to me. Prove it to yourself. Maybe I will. You won't." The story only really grabs in the last pages, when it leaves the likely facts for pure supposition.

The sections treating the band's career seem like a structural mistake. If we assume they're not actual flashbacks, then as impositions from above they only dilute the psychodrama of Edwards's last days. They skim lightly, knowingly, over acres of more-or-less known pop-cultural history, giving just enough detail for anyone not sufficiently up on the band. True fans will end up skipping, especially if they have read Simon Price's band biography, Everything.

Myers gives Price a special credit in a bibliography that also runs to the likes of Yukio Mishima, Albert Camus and Guy Debord – all inspirations for Edwards himself. In the end, it's this sense of literary ambition that damns the book. You can't imagine Richey giving it the time of day.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments