Review: "Roth Unbound: A Writer and His Books", By Claudia Roth Pierpont

A study of a feted author that reflects on his life through the rich imagination of his novels

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

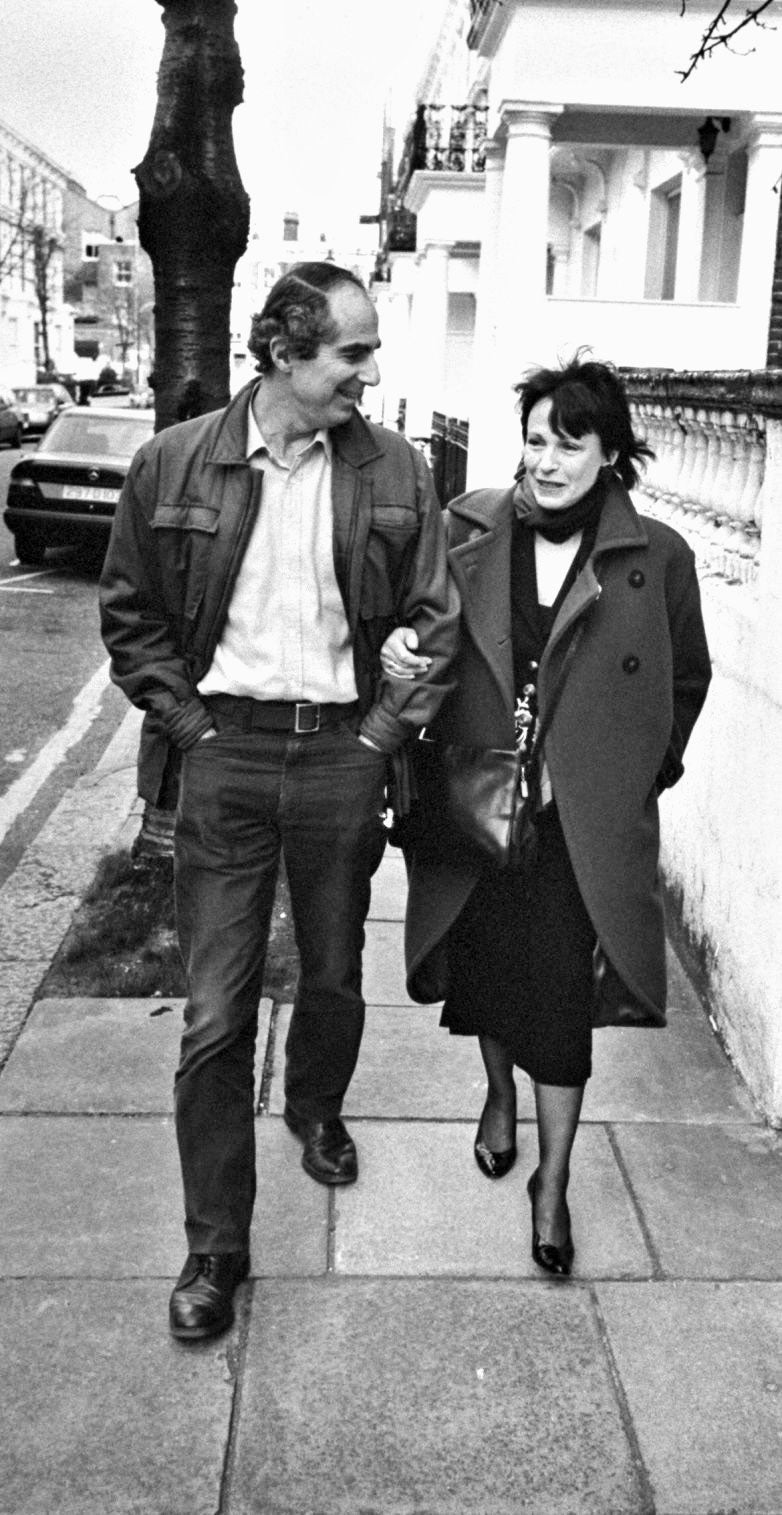

Your support makes all the difference.The curse of the novelist is the question ‘Is it autobiographical?’ Is writing down of the events of one’s own life considered to be more authentic than the exercise of the imagination? Philip Roth must have been plagued more than any other writer with this dumbest of demands. For he writes out of his native Newark, sends his characters to his own high school, makes novelists his narrators, and calls one of his characters Philip Roth. After his second wife, the actress Claire Bloom, wrote a tell-all memoir of their marriage, he wrote an answering novel, in which an actress writes a memoir of her failed marriage to a radio star.

Sooner or later there will be a biography. James Atlas has already crawled all over Saul Bellow and Delmore Schwartz and we are bound to hear the laments of Roth’s many ex-girlfriends and perhaps the children of his first wife, as well as friends and editors. Yet a new book, Roth Unbound: A Writer and His Books, by Claudia Roth Pierpont (no relation, literary Roths are legion – Joseph, Henry, Philip) binds the books to the man not by mining them for nuggets of autobiographical information but by talking to Roth himself about what he put into them, by which she doesn’t mean the facts, but the territory of imagination and self that creates fiction.

Pierpont met Roth in 2002. A couple of years later she received a letter from him responding to a New Yorker article she had written. Roth, it turns out, has a habit of writing to the authors of writing he admires. This impulse led fortuitously to a series of meetings and eventually the idea for a book which began after he had completed Nemesis and announced his retirement. It has grown out of conversations with him and research in his personal files in the attic of his Connecticut house. Unlike a biographer, she has not interviewed other sources. Like a critic, she has made her own judgements about the work. What emerges is his charm – he has certainly charmed her. “He loves to listen: he’s as funny as you might think from his books, but he makes the people around him feel funny too – he may be the easiest laugher I’ve ever met.”

Roth Unbound is a chronological survey beginning with the attempts to silence him by a prominent New York rabbi in 1959, after the publication of his first collection of short stories depicting, the rabbi complained, “such conceptions of Jews as ultimately led to the murder of six million in our time.” Jewish America in those days was still touchy. There had been no writer quite like Roth before, who wrote out of the growing disconnection between immigrant gratitude and the expectations of those born to be, and feel them selves to be, Americans, not special cases. A writer who had no objection to airing the dirty linen of his people because everyone has soiled underwear, and to be part of everyone is the desire. The attacks left him in a state of shock, and this is before Portnoy’s Complaint. It is salutary to be reminded that one of the greatest living writers has been assaulted with almost every book he has written.

Pierpont excavates Roth’s disastrous first marriage in the Fifties to an apparently mentally unstable woman. We can draw such conclusions as we wish from his portrayal of women in his work. Pierpont defends him against accusations of misogyny (levelled by me, among others). Roth, throwing up his hands in bewilderment, says he loves women, and there have been no shortage of girlfriends before, during and after his two marriages. He is open about the women (and men) who inspired his characters. What Pierpont has achieved is to defeat speculation. Whatever we think we know, turns out to be wrong. Which is, of course, one of the great themes of his masterwork, American Pastoral.

I don’t know what Roth thinks of creative writing courses. He has taught, but he teaches literature already written. On page 146, he reveals how his novels come into being: not through a plan, a theme or a message, but a groping forward. “The first draft is really a floor under my feet,” he says. “What I want to do is to get the story down and know what happens... The book really comes to life in the rewriting... What it’s about is none of your business... By the third draft I have good picture of what my concerns are.” This may be one of the most important counters to creative writing theory I’ve read, for its describes writing as an intuitive process. Roth’s friend, the Israeli novelist, Aharon Appelfeld, told me he thought that writers were stupid people because they don’t know what they are doing.

Pierpont locates, correctly in my view, the highest peaks of his achievement in two not-quite-consecutive novels, Sabbath’s Theater and American Pastoral. In the former he laid aside post-modern tricks, the character as mask, the constant dialectic which is the essence of Talmudic disputation, and told a story.

Roth, sitting on a white sofa in his elegant Connecticut living room, explains to Pierpont that he could not stand to have Mickey Sabbath in the house, that he was sick to death of his cynicism and nihilism by the time he had finished with him. It was relief to turn to [American Pastoral’s] Swede Lvov, a good man. As far as America is concerned, he reveals himself as a patriot. The study of American society in American Pastoral, almost an historical novel, comes from his understanding of consciousness. If you neglect it, he says, you write popular fiction; consciousness without the gravity of experience leads to “the failed experiment” of Virginia Woolf where it so dominates the novel that “it ceases to move through time the way a novel needs to.”

Roth’s consciousness, moving through time, from the young Jewish boy in the fifties recently released from national service, trying to write, to the exhausting, difficult (for him) novellas of his seventies are the history of post-war America and a charting of the history of the male psyche with all its wayward desires and impulses. If Roth does not, and I still believe he doesn’t, understand women, my God, does he understand men.

John Updike, part friend, part rival, neither of them easy with the other, compared him at one point to Bach, meaning that same repetition of, and revolution around, themes. Bach was a mathematical composer, Roth is a roarer, a boiler igniting into life.Life is what it’s all about. I let out a shriek of rage when I heard on the radio that Saul Bellow had died. That Roth is living makes life worth living. Then we’ll have the books. Nothing else to know.

Roth Unbound: A Writer and His Books By Claudia Roth Pierpont (Jonathan cape, £25) Order at the discounted price of £20 inc. p&p from independent.co.uk/bookshop or call 0843 0600 030

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments