Posthumous Cantos by Ezra Pound; edited by Massimo Bacigalupo, book review

Bacigalupo addresses Pound's culpability with what we might call a light touch

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.During the second world war, Massimo Bacigalupo's grandfather was a pharmacist in Rapallo, and Ezra Pound one of his customers. This personal connection was carried on by Bacigalupo, now a professor of American literature at the University of Genoa, who as a young man "contracted a debt with Olga Rudge and Dorothy and Ezra Pound, who put up with [his] youthful impertinence".

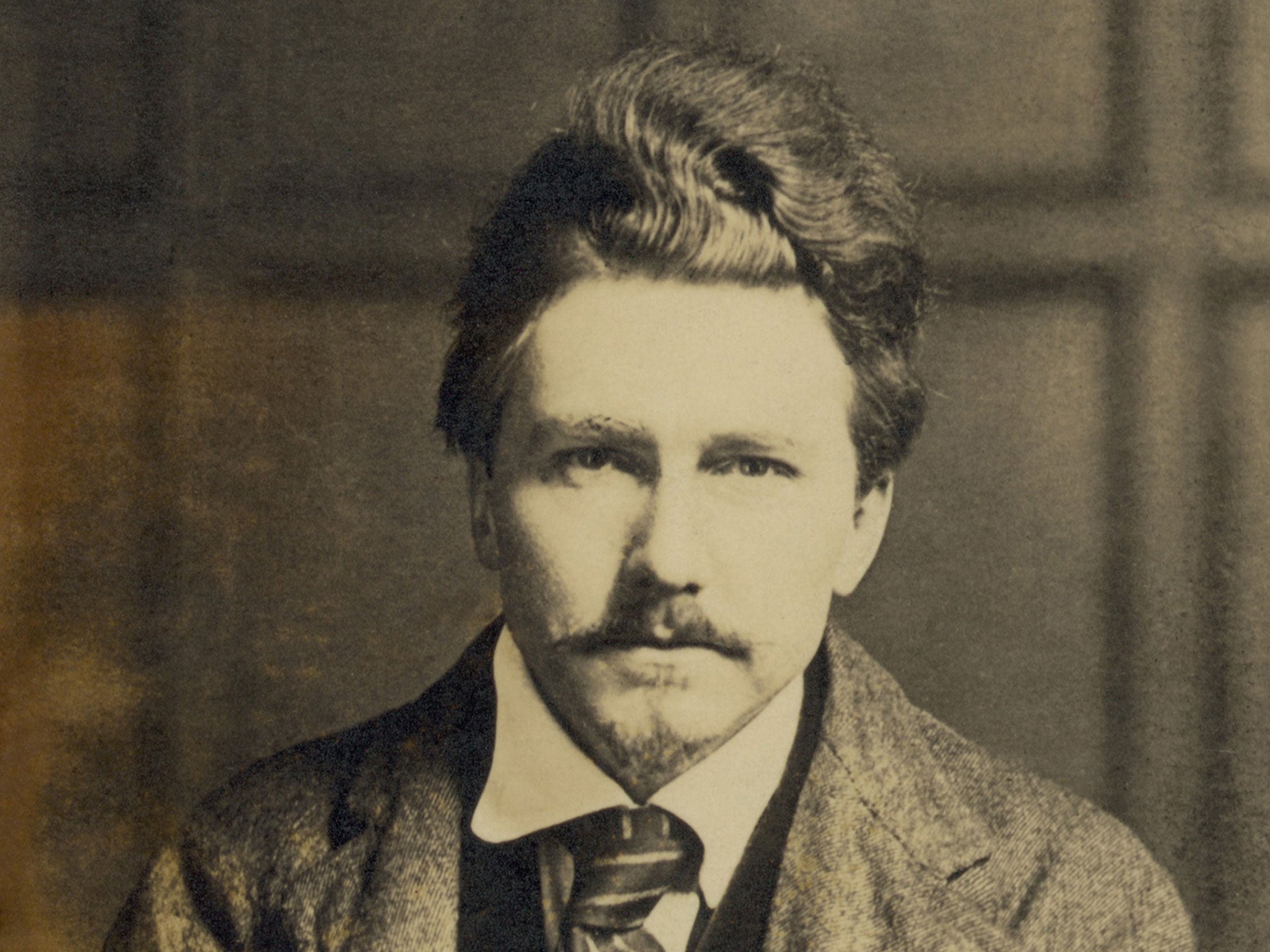

It's against this background that his edition of Pound's Posthumous Cantos must be read. No contemporary study can ignore the poet's notorious collaboration with Italian fascism: not merely because it raises questions about whether an artist's work has a moral existence separable from the artist's own but because the Cantos' project is precisely to close any such gap. Pound planned them as "a history both of the world and of himself", as Bacigalupo puts it. In his well-organised supporting materials, which include a chronology of the poet's life and extensive notes on the texts themselves, this editor addresses Pound's culpability with what we might call a light touch: "Pound did not grasp at first the enormity of events, or what his collaboration with the Italian state radio would cost him."

What to make of this inseparable work and life? Of Pound's seductive energy, man-of-the-world abbreviations, intellectual shorthands, and characteristic piled-high allusions? "sold 7 ways cross-wise. betrayer /& hyper-betrayed /& Edda floated around in the waters /along with the other nurses /ready for anything 'Tranne nella casa del re'", reads a characteristic passage from the Pisan notebooks.

It might have been better to call these "Uncollected Cantos". They are gleanings from Pound's abandoned drafts and from his backlist of poems published only in periodicals. Yet Pound's prolix, reiterative composition processes mean that the material is genuinely interesting, and a real addition to his canon. Bacigalupo has based his edition on one he first published in Italy in 2002. Now he has also translated Pound's unpublished Italian verse. The drafts for Cantos 72-3, and later drafts for mystical, quasi-mediaeval verse, written in 1944-5, are composed in stylised, often archaic Italian. Their very technique expresses the nostalgia that is so often the flip side of fascism.

For the Cantos do succeed in closing the gap between the artist and his work. Their layered quotations, so often anachronistically juxtaposed, are a ceaseless dispersal of authority, a continual delegation of responsibility for truth telling. They show us moral relativism in action, as when he quotes Rudolf Hess: "O grass my uncle, that are nowhere out of place".

This feels not so much modernist as post-modern. But Pound was no philosopher. The impatient brilliance of his best effects may have been nothing more than a desire to keep the verse moving: something we see in the long snaky columns on the page. But such impatience can be morally slapdash. That it does "not grasp at first the enormity" of its actions is neither alibi nor excuse.

Carcanet, £14.99. Order at £13.49 inc. p&p from the Independent Bookshop

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments