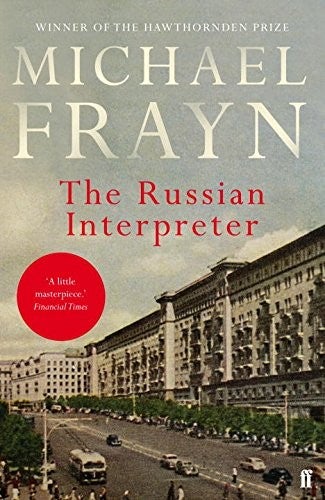

Paperbacks: From The Russian Interpreter to All Day Long

Michael Frayn was himself a student and Russian interpreter in Moscow in the 1950s, and this novel conveys the atmosphere of that time: seedy, cold, grumbling, paranoid

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Russian Interpreter, by Michael Frayn.

Paul Manning is a student in Moscow in the Cold War years, working on a thesis unmemorably titled “The Experience of De-Centralisation in the Administration of Public Utilities”.

He regards it as a terrible burden, a sick, ailing child that he has to nurse; “[B]ut perhaps when it had grown up and become a PhD it might keep him in his old age”. Meanwhile, Manning fights battles with the university bureaucracy, goes to restaurants and drinks vodka, and walks the Moscow streets with his Russian friend Katya, listening to her talk about philosophy, religion, and politics.

He becomes friends with Proctor-Gould, a fussy, eccentric English businessman who speaks no Russian. Manning agrees to act as his translator and is soon interpreting between Proctor-Gould and his Russian girlfriend Raya, which is painful because Manning desperately fancies her himself.

Raya is an enigmatic character; beautiful, unconventional, carefree, a kleptomaniac. She moves in with Proctor-Gould and steals his tins of Nescafé, as well as his books. But what exactly is her game? Manning soon gets drawn into a world of subterfuge and espionage, without for a moment meaning to.

He finds himself an object of interest to the security forces and is followed through the streets.

Michael Frayn was himself a student and Russian interpreter in Moscow in the 1950s, and this novel conveys the atmosphere of that time: seedy, cold, grumbling, paranoid. Yet this is a funny novel.

Frayn focuses on the absurdities of this bleak world and makes comedy of it, just as Isherwood did for 1930s Berlin.

Manning is a first-rate comic protagonist, observant yet innocent, rather like one of Evelyn Waugh’s put-upon heroes. A short novel, but a highly enjoyable one, with characters that jump off the page. It’s a great pity that Michael Powell, who was going to make a film of it, never did.

Faber & Faber £8.99

Weathering, by Lucy Wood

“Arse over elbow and a mouthful of river”, begins this novel, and we are plunged into an extended description of a woman, Pearl, struggling and flailing around in the water, her body reduced to grey dust, swept along by the current.

Cut, then, to Pearl’s daughter Ada and grand-daughter Pepper, who have moved into the old cottage in the sodden valley where Ada grew up, now that Pearl is dead.

Ada had been estranged from her mother for 13 years; sorting out the house brings back a flood of memories, while six-year-old Pepper, “lucid and morbid”, soaks up her new surroundings, and makes private, perceptive observations to herself.

They don’t intend to stay permanently; yet gradually find themselves settling in, forging connections with old and new friends, as Pearl’s ashes continue their journey towards the sea. The novel is heavy with atmosphere and lyrical descriptions.

Very fine prose, but too careful, the sentences too obviously polished; for me a little too redolent of the creative writing class.

Bloomsbury £8.99

Swallow This, by Joanna Blythman

An eye-opening exposé of the food industry, Swallow This makes you realise just how much supermarket food is processed. Not just the ready-meals but the “artisan” sourdough loaves, the “traditional” vintage cheddar cheese, the probiotic drinks, and bottles of cooking oil.

There are chapters on the industrial scale of food production, on a visit to a food industry trade fair (the only selling point of new products is that they save supermarkets money), the practice of “clean labelling” (making ingredients sound more natural than they are), and on the uses of starch, water, oil, sugar, and colourings in food.

Let’s all try to eat more healthily in the new year; but be warned, the supermarkets aren’t making it easy for us.

Fourth Estate £8.99

The Poet’s Tale by Paul Strohm

Paul Strohm focuses on one year of Chaucer’s life in this vivid piece of historical re-creation. In 1386, Chaucer was a customs official in London – a delicate job which meant being seen to enforce the law while not damaging the profits of powerful men who made fortunes from the wool trade.

His accommodation was a rent-free chamber at Aldgate, under which royal processions, drovers, traders, carts, rebels and convicts passed in an unending stream.

In 1386, he lost this post for political reasons and retreated to Kent where he began The Canterbury Tales.

It seems a wonder that from such a turbulent, hierarchical, and violent society Chaucer’s humane and civilised poetry emerged; and this book made me keen to revisit it.

Profile Books £9.99

All Day Long by Joanna Biggs

Subtitled “A Portrait of Britain at Work”, this is a cross-section of jobs that British people are doing on any given day.

Joanna Biggs has interviewed them: a prostitute, a rabbi, a fishmonger, a shoemaker, a nurse, a scientist, a crofter, a CEO, and an intern, to name a few. It’s a thought-provoking glimpse of a day in the life of a modern society, and Biggs’s sympathetic approach encourages people to open up. It’s full of entertaining observations.

I enjoyed learning from Thomas Eaton, a quiz question writer, that on The Weakest Link they had to avoid questions involving the words “apocalypse”, “Antarctica” and “Rusedski”, because Anne Robinson couldn’t pronounce them. A first-rate piece of social reportage.

Serpent’s Tail £8.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments