Paperback review: From Yes Please, by Amy Poehler to The Moor: A Journey into the English Wilderness, by William Atkins

Aslo The People’s Republic of Amnesia by Louisa Lim, Noontide Toll by Romesh Gunesekera and The Other Child by Lucy Atkins

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Moor: A Journey into the English Wilderness - By William Atkins - Faber £9.99

We’re living through a golden age of bookish, perambulatory nature writing: I think of recent works by Olivia Laing, Philip Hoare, Robert Macfarlane. And now we have William Atkins’s excellent The Moor. How it failed to win any major awards is beyond me. Perhaps, like its subject, it is rather too mysterious and elusive – or too bloody creepy – to win over your average literary prize panel.

The premise is simple: Atkins walks over England’s moors, from Exmoor to Alston, describing the landscapes and wildlife he sees, and weaving in the stories of those who went before – such as Henry Williamson, author of Tarka the Otter, for whom the blasted moors of the South-west were reminiscent of the battlefields of northern Europe, and Emily Brontë, whose Yorkshire Moors were like “a sea … stretching into infinity”.

The pace of the book is slow, deliberate. But that seems only appropriate. As Atkins explains, moorland is often treacherous; a mis-step can leave you knee-deep in peaty bog. And the mind, too, can take wrong turns in such places. We learn of Sylvia Plath’s visit to Haworth with her husband Ted Hughes, who recognised later how “the empty horror of the moor” reflected something of her inner life. Atkins suggests how, as with expanses of ocean or desert, moorland can have sinister effects. The eye slides over the horizon in search of particularity. Thoughts run away with themselves.

Yet for all the trudging pace and the unsettling themes, the book is a pleasure to read, and that’s thanks to Atkins’s superb prose. His writing is a tour-de-force of noticing: He picks out the “gnatty haze” above the heather; the movement of a starling murmuration, like “a reel of film slipping off its spool”. Even after 400 pages of this meditation on the moor you’re left wanting, well, more.

The People’s Republic of Amnesia - by Louisa Lim - Oxford University Press £10.99

Louisa Lim’s book explores the legacy of the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989, which China’s rulers have sought to expunge from the collective memory. In this they have been largely successful; but Lim finds and interviews those still haunted by what happened – from the artist Chen Guang, a soldier who participated in the brutal crackdown on the student protests and who now paints to assuage his guilt, to the so-called Tiananmen Mothers who bravely campaign on behalf of the victims.

This is an impressive work of investigative history, and Lim makes unsettling discoveries, such as the silver watches given to the soldiers of 1989 as souvenirs to celebrate their “Quelling of the Turmoil”. Reading this, I felt the same sort of revulsion as when watching Joshua Oppenheimer’s recent documentaries about the Indonesian genocide; it’s that sense of looking on helplessly as history is retold by the victors, and warped in the retelling.

Noontide Toll - by Romesh Gunesekera - Granta £8.99

Vasantha is a van driver for hire. As he ferries passengers around Sri Lanka he encounters aid workers, young soldiers grappling with war guilt, tourists. Each chapter describes a different journey, and so Gunesekera’s book comes to resemble a collection of short stories, linked together by Vasantha’s shrewd, genial voice. As a driver, his biggest fear is falling asleep at the wheel – and that means he’s attuned to the soporific tendencies of others, those “sleepy grey heads” who want to forget about the country’s past. In contrast, Vasantha vows never to “give up on the stories that make us who we are”, and his narration provides Gunesekera with the perfect vehicle for acute observations on Sri Lanka’s tragic recent history.

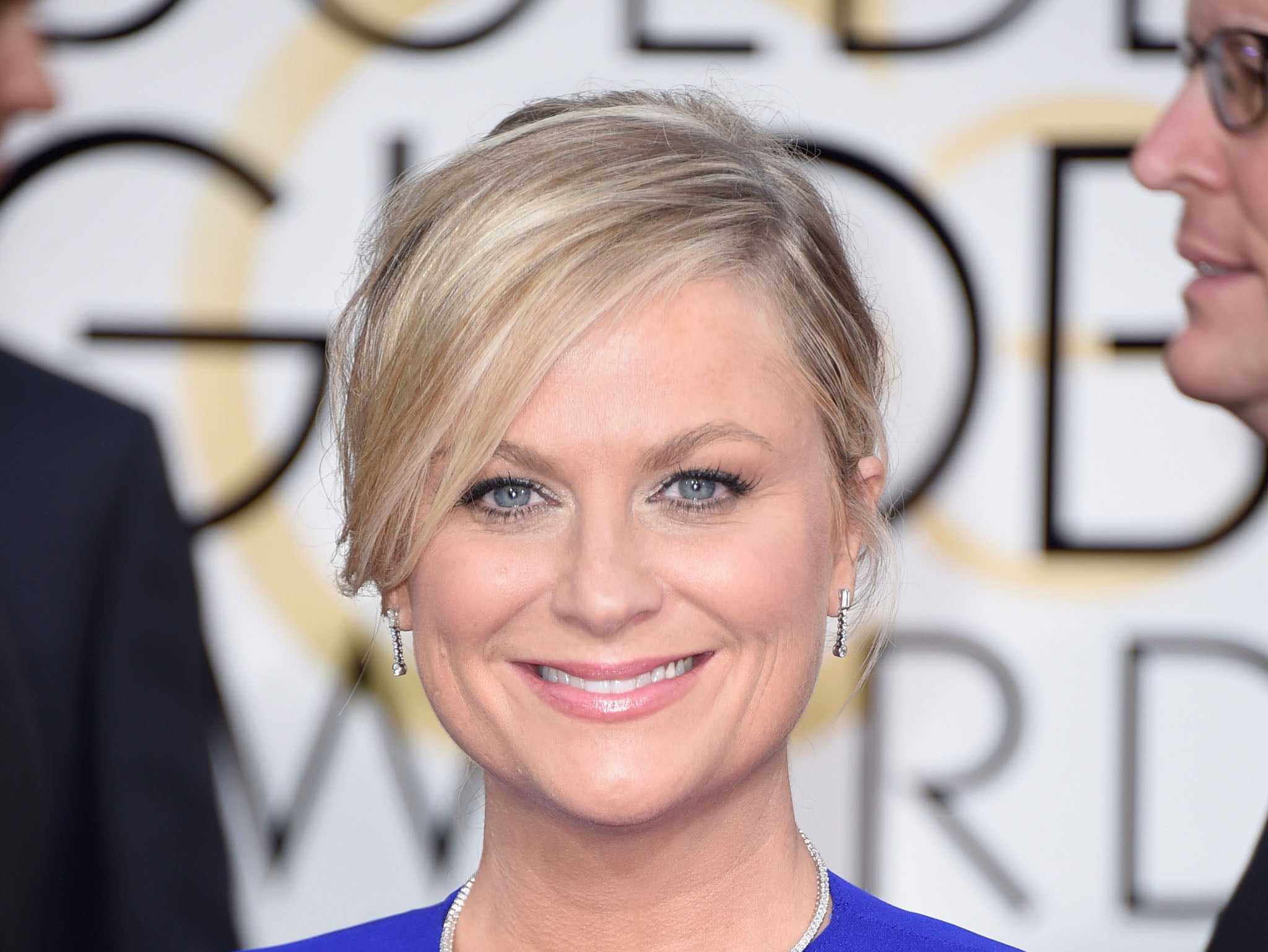

Yes Please - by Amy Poehler - Picador £9.99

Your average celebrity autobiography is a predictable affair: the star joins the dots to inform fans of how he or she became rich and famous. Amy Poehler’s book, thankfully, bucks the trend. A Golden Globe-winning actress and writer, best known for her appearances on Saturday Night Live and Parks and Recreation, Poehler revisits her hungry years doing improv comedy in tiny theatres, and delivers name-dropping anecdotes from her time in Hollywood (“Matthew McConaughey wore a sarong …”; “I made a drink for James Gandolfini”). But the focus is on her lingering fears and insecurities, and other intimate things, such as her experience of her body during pregnancy. It’s clever and touching, and, needless to say, very funny.

The Other Child - by Lucy Atkins - Quercus £7.99

When single mother Tess meets paediatric surgeon Greg – late forties, dashing, American – she quickly falls in love. She also falls pregnant, and Greg doesn’t seem overjoyed by the news. When he gets a new job in a Boston hospital, the whole family relocates to the US. There, secrets from Greg’s past come to light and tensions and jealousies simmer to the surface. Lucy Atkins does characterisation very well: her characters speak as real people speak, and behave as real people behave. But there’s an annoying tendency here to recap the plot every few chapters – this is perhaps necessary, given the narrative’s many twists and turns – and the revelations at the end arrive mostly via Tess’s email inbox, which saps the drama a bit.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments