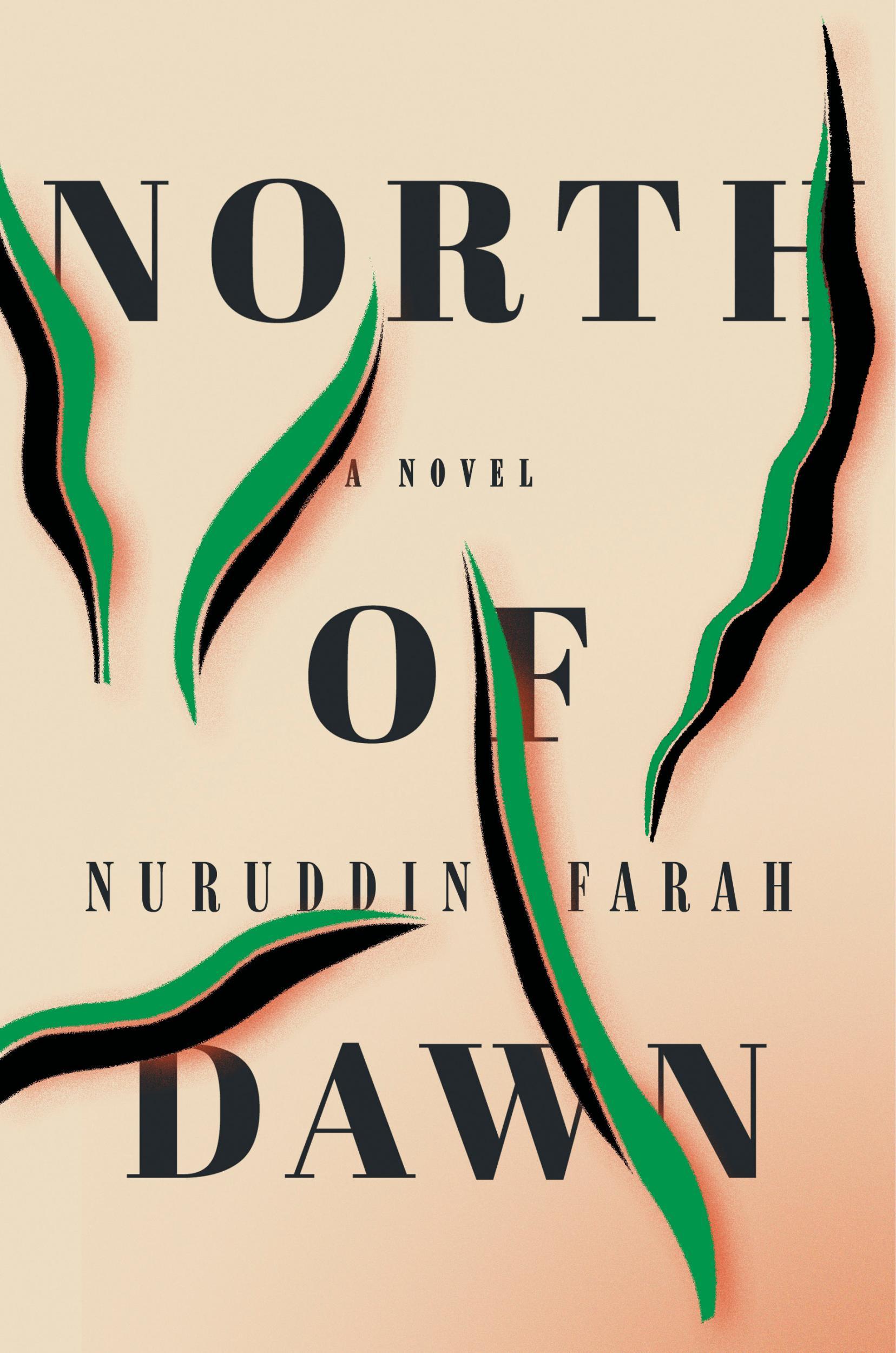

North of Dawn by Nuruddin Farah, review: The Somali novelist channels the pain of his sister's death in a terror attack

This novel offers a rare perspective, exploring the conflicted grief of the family of a suicide bomber

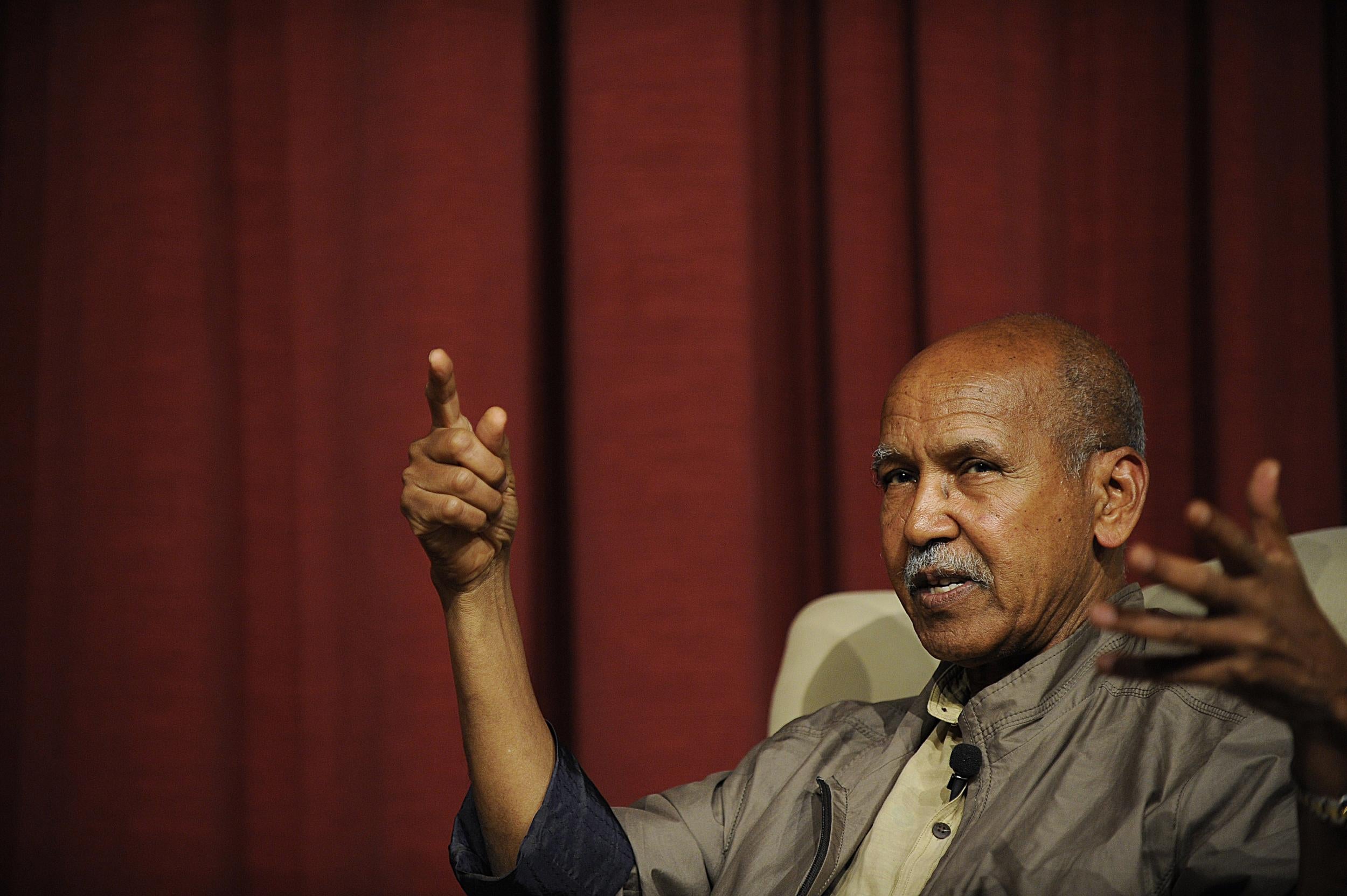

When Nuruddin Farah writes fiction about the ravages of terrorism, the details may be imaginary but the scars are real. The celebrated Somali novelist, a frequent contender for the Nobel Prize in Literature, lost his sister Basra Farah Hassan in 2014. A nutritionist working for Unicef, she was murdered, along with at least 20 others, when the Taliban bombed a restaurant in Kabul.

Farah’s new book, North of Dawn, places its characters far from flying shrapnel but deep in conflicted grief. Like his previous novel, Hiding in Plain Sight, it’s concerned with difficult questions of forgiveness and recovery in the aftermath of violence. The story opens in Oslo, when a Somali diplomat named Mugdi gets word that his only son has blown himself up at the airport in Mogadishu. Mugdi and his wife, Gacalo, suspected their son was radicalised, but news of his death makes it impossible to ignore the truth any longer: They are the parents of a suicide bomber.

Shocked and disgusted, Mugdi wants nothing to do with the memory of his late son. “How can I mourn a son who caused the death of so many innocent people?” he asks. “I explode into rage every time I remember what he did.” But his wife refuses to relinquish her love for the young man, and she’s determined to keep their parental connection alive by inviting their son’s widow and her two children to Oslo. That invitation, sent on the wings of affection and duty, ensnares Gacalo and Mugdi in a complicated kindness that will alter the rest of their lives.

North of Dawn is a story we rarely hear, a tale concerning the terrorist’s family that takes place in the long shadow of grief, shame and twisted loyalty. It’s also a story pulsing with the adrenaline of our era: a toxic mix of zealotry and xenophobia.

It’s not hard to imagine that Farah, who currently lives in South Africa, has infused the protagonist of this novel with his own dismay. Mugdi is a Somali who “detests Somalia’s dysfunction”. He’s a foreign-born resident who fears his host country’s growing intolerance. He’s a spiritual man who has lost his faith in organised religion, though “the ringing of the muezzin stirs memories within him”.

As the novel opens, Mugdi is thrust into the awkward role of welcoming a daughter-in-law poisoned by the same radicalism that turned his son into a killer. She arrives from a refugee camp in a state of terrified bewilderment, fully cloaked, unwilling to speak to him – or any man – directly. Even before they’ve left the Oslo airport, we can see the clash of secular and religious values that will confound this awkward new family. When Mugdi asks her to fasten her seat belt, she announces: “We’ll die on the day that Allah has ordained for us to die, whether we wear this thing or not.” The test of wills has just begun.

North of Dawn is bracingly honest about the difficulties of assimilation, the way hospitality curdles into condescension and gratitude sours into resentment. Mugdi and his wife are extraordinarily generous towards their daughter-in-law, a young woman named Waliya, but Mugdi expects her to reciprocate by going to language classes, finding a job and becoming a productive member of Western society. Waliya, for her part, remains unwilling to do anything that might contaminate her. Alarmed by the permissive culture of Norway, she’s intensely alienated from her new home and determined to cling to her conservative practice of Islam ever more fiercely.

But for Farah, Muslim radicalism is not a problem in isolation. It’s merely one side of the coin of intolerance that’s gaining currency in liberal democracies. “We are caught,” a friend tells Mugdi, “between a small group of Nazi-inspired vigilantes and a small group of radical jihadis claiming to belong to a purer strain of Islam.” His wife agrees: “We must all beware of provocateurs, no matter their allegiances, who are enemies to the nation at large and of peace everywhere.”

This is such a timely, necessary argument, but I wish it were expressed more gracefully in these pages. North of Dawn suffers from a ramshackle quality one might expect from an exciting but not quite finished draft. There are strange gaps in the plot, and the prose sometimes slips into antique cliches. Confronted by an aggressive woman at his front door, Mugdi suspects “that she has cased the joint”. Another character “moves like greased lightning and is at the cafe huffing and puffing”. And Farah’s characters sometimes speak in weirdly artificial ways. A teenage girl says to her boyfriend, “Nothing would give me more joy than to come with you and to make their acquaintance” – a remark that would sound more natural in a Regency romance.

More irritating, these characters often feel compelled to turn away from each other and look out directly at the reader. With preternatural eloquence, Mugdi’s 17-year-old grandson declaims: “Somalis pay lip service to the faith while we live a life of lies. This is why the dissonance in our hearts continues to flourish, why there is no letup in the usual struggles within our minds, why the strife in our land rages on unabated.”

If Farah wants to make this powerful and beautifully phrased observation, he would do better to place it in an essay instead of cramming it in the mouth of a boy who would rather be playing soccer with his buddies. The story Farah shows us through these characters’ derailed lives is more illuminating than anything they can explain to us.

‘North of Dawn’ is out now on Prentice Hall Press, £19.99

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks