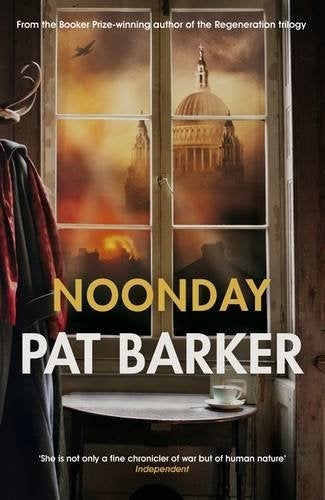

Noonday, by Pat Barker - book review: Fine art shines through London’s darkest hours

Hamish Hamilton - £18.99

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The two World Wars were defining communal traumas for the 20th century. And they have inspired towering artistic works, although with delays in their birth between different disciplines. Most of the greatest poetry and fine art has elements of reportage, appearing during each war or soon after, while literature has frequently been more retrospective.

Pat Barker has drawn on both approaches, incorporating real creative individuals from wartime periods into her fiction, lending it resonances from the dramatic intensity of their lives and works, while also benefiting from the longer view afforded by history itself.

This strategy has been complemented by her focus upon social and psychological issues that mainstream culture had previously largely ignored. Her first book, Union Street, dates from 1982 and is a feminist classic on working-class women which is still widely read. But she is most famous for the Regeneration trilogy of the 1990s, which used the experiences of Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon to explore the male psyche and its descent into darkness during the First World War. The trilogy’s final volume, The Ghost Road, won the Booker Prize in 1995.

Noonday is the conclusion of another wartime series, the Life Class trilogy, which can be seen as an extended coda to the earlier work, this time examining war from the perspective of fine artists. Its main characters are Paul Tarrant, Kit Neville, and Elinor Brooke, who all met at the Slade School of Fine Art as the First World War broke out and who are now in middle age. Previous volumes – Life Class and Toby’s Room – were set around that war, but this one deals with the Second World War. Straddling two cataclysmic conflicts in the same series is a bold move and is not entirely successful for Barker.

In Noonday she deals with the Blitz, that horrifying period when the Home Front transmogrified into the frontline. Yet the novel’s hard-hitting opening deals with tragedy unrelated to warfare, as Brooke’s mother slowly dies in her country home, her strained breathing dominating the household.

The narrative then switches to London, where Brooke and Neville are volunteer ambulance drivers and Tarrant is an air-raid warden. The trio attempt to keep calm and carry on as they tackle carnage by night and pursue culture by day.

Barker’s writing is versatile. She describes with graceful ease the way façades are blown from buildings, turning private space to public: “On the first floor, a green brocade armchair cocked an elegant cabriole leg over the abyss.” Elsewhere, she gives unflinchingly direct descriptions of gore and mutilation. However, for Barker prose is foremost a tool for clarity rather than a vehicle for style, so that clichés and other infelicities can encroach: “The raids came thick and fast ....”

A centrepiece of Noonday is a real incident, the bombing of an East End school in which hundreds of locals had taken shelter. Some of them are known to Tarrant and a spiritual medium, Bertha Mason, latches on to his distress. Spiritualism is a recurring feature in Barker’s fiction and here it becomes a connecting thread between the two wars, as desperate Londoners search for their loved ones in the afterlife, vulnerable to chicanery.

The portrait of Mason is the strongest part of the novel, unforgettable both for a persuasive account of her macabre inner life and its evocation of her sordid and lawless existence, “a grotesque Persephone, claiming to speak for millions of the mouthless dead”.

Elsewhere, Barker’s characterisation is problematic. The Life Class trilogy does not use real-life creative artists as main players in the way the Regeneration trilogy does, instead offering them as composites and in cameos, and this may partly explain why this series lacks the other’s depth and texture.

This weakness is accentuated in Noonday by a thematic deficit. While Life Class addressed the role of art in war, and Toby’s Room confronted the disfigurement and deformity that it causes, both literal and metaphorical, Noonday falls back upon a plot around infidelity that can seem mechanical.

And what of the history itself? Barker’s treatment of the Blitz is not wholly faithful. It airs the sexual escapism prevalent in the blackout, but misses the startlingly widespread looting and crime. We did not all pull together back then and this is a surprising omission by Barker, normally a reliable chronicler of unpalatable historical truth.

Nevertheless she delivers a virtuoso rendition of the bombing, as huge swathes of London blaze away with the brightest of bright lights ever, pyres for tens of thousands of residents, none of whom know, as daylight fades, whether they will hang on through another night of onslaught from high explosives. Barker shows us how the city’s finest moment was indubitably also its most terrifying, with luminous and unsparing insight.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments