No Need for Geniuses: Revolutionary Science in the Age of the Guillotine by Steve Jones, book review

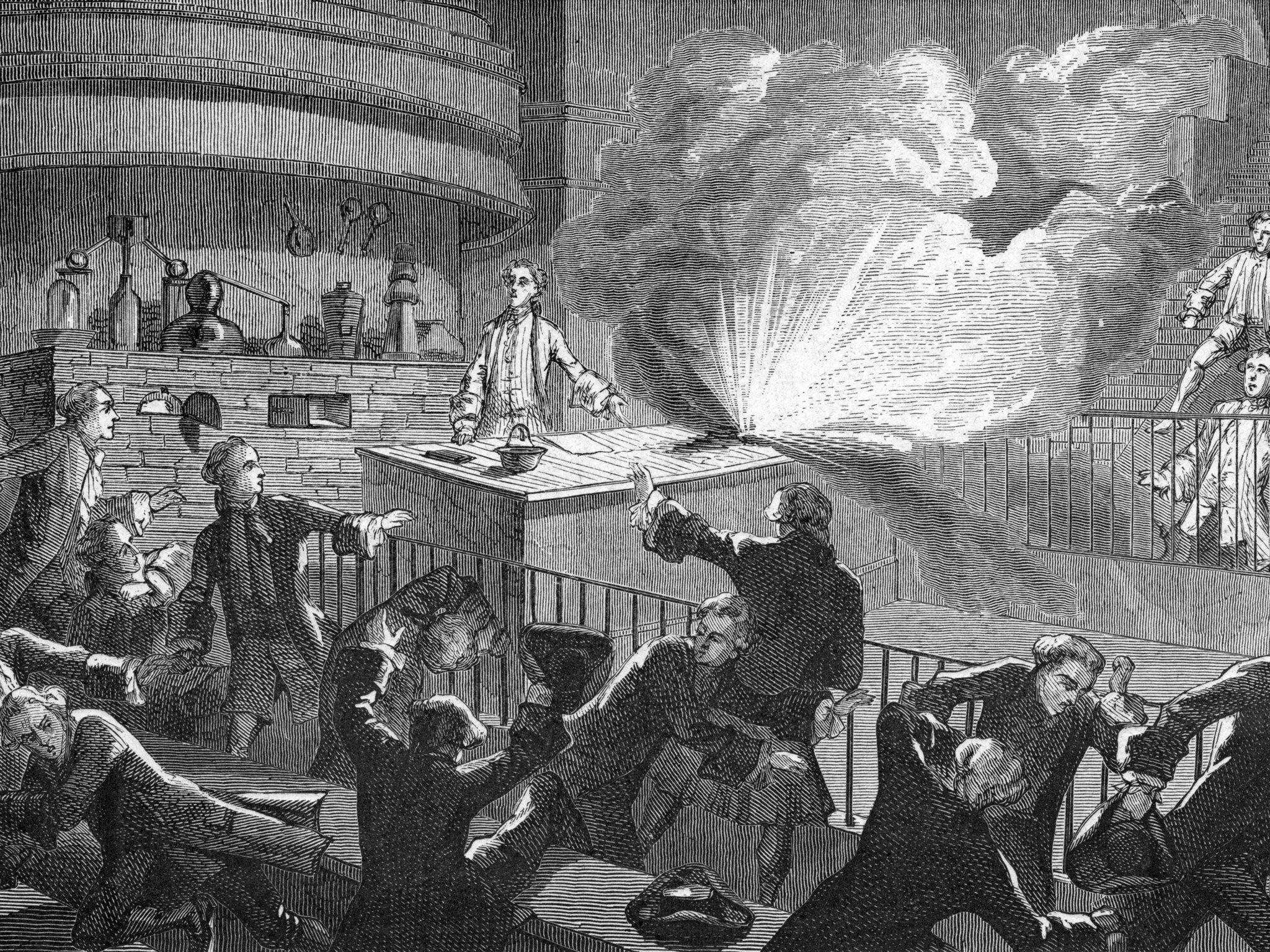

Scientists were among the first to be targeted in revolutionary France

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Zhou Enlai, the first Premier of the People's Republic of China, might have felt it was too early to judge the French Revolution but I think the rest of us are now permitted to voice an opinion. Not only did the Revolution and the following Napoleonic period have a lasting effect on the law (the Code Napoléon) and civil liberties (the emancipation of many of Europe's Jews), but much of modern science and technology began then and there.

The world system of weights and measures, based on the kilogram, metre and second, has lasted to this day; modern chemistry began with Antoine Lavoisier's first list of truly elementary substances; modern cartography began at that time; the unit of electrical current is named after André-Marie Ampère.

But even more than that, Steve Jones shows just how much the scientists, radicals and intellectuals were intertwined: Marat studied medicine at St Andrews, Scotland; Laclos (Les Liaisons Dangereuses) invented the modern artillery shell; Robespierre's first case as a lawyer was an action concerning the new-fangled lightning conductors.

The French Revolution was in part stirred, intellectually at least, by the enormous leaps in science at the time. Surely, the philosophers reasoned, if we have obtained certain knowledge of the pure elementary substances – oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen etc – perfect human knowledge and perfect human beings must follow.

It is, of course, notorious that the Revolution devoured its children; the scientists were among the first to be consumed. Despite being crazed radicals, when it came to science, the Jacobins soon turned to the traditional conservative argument, formulated in England by men such as Samuel Johnson and Edmund Burke, that science was contrary to human morality: "What do the diverse hypotheses by which certain philosophes explain the phenomena of nature matter to legislators" (Robespierre).

Hence Jones's title, words believed to have been uttered when an unsuccessful plea was made to save the most distinguished scientist of all, Lavoisier, from the guillotine. Tyrants have always come to the same conclusion: Hitler had no need of scientific geniuses – many of them were Jewish. Stalin could tolerate no science that contradicted the revealed truth of dialectical materialism. Jones takes the discoveries that were made over 200 years ago and brings them up to the present day.

Apart from a distinctly off-piste, almost 40-page, excursion on the Tour de France, these updates earn their keep. The most telling topic is the element nitrogen, around which Jones weaves a tour de force in half the pages he devotes to the Tour de France. This supposedly inert element, which makes up 78 per cent of the atmosphere, is revealed to be an exemplar of science's ambiguousness. Lavoisier knew that nitrogen was the key to both the fertility of the soil and to gunpowder, and set about improving both. At least two billion people on the planet would starve but for the trick of capturing atmospheric nitrogen to make fertiliser. On the debit side, nitrogen is the basis of all non-nuclear explosives which, since the French Revolution, have killed about 200 million people.

Jones brings all his rationalist scorn to bear on the absurdities human beings employ to torment themselves and more often each other. Jones long ago perfected a style that goes way beyond the cover blurb ("a master story teller"): he strings together narratives of bizarre chains of grotesque unlikeliness which nevertheless happen to be true. The story of gunpowder involves the revelation that colonial Britain used to acquire saltpetre for gunpowder from India, the ultimate source being human excrement. Moving on to the issue of artificial fertiliser for the soil, Jones observes: "Britain, the proud harvester of Indian evacuations, was reluctant to appeal to the rear needs of its own citizens to improve the nation's farms."

Jones is a genius who can spin seamless moralities and lugubrious commentaries on human vanity, greed and ugliness while informing us about life on our planet in the clearest terms.

Little, Brown, £25. Order at £21 inc. p&p from the Independent Bookshop

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments