No Enemies, No Hatred: Selected Essays and Poems, By Liu Xiaobo, edited by Perry Link, Tienchi Martin-Liao and Liu Xia<br />June Fourth Elegies, By Liu Xiaobo, trans. Jeffrey Yang

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

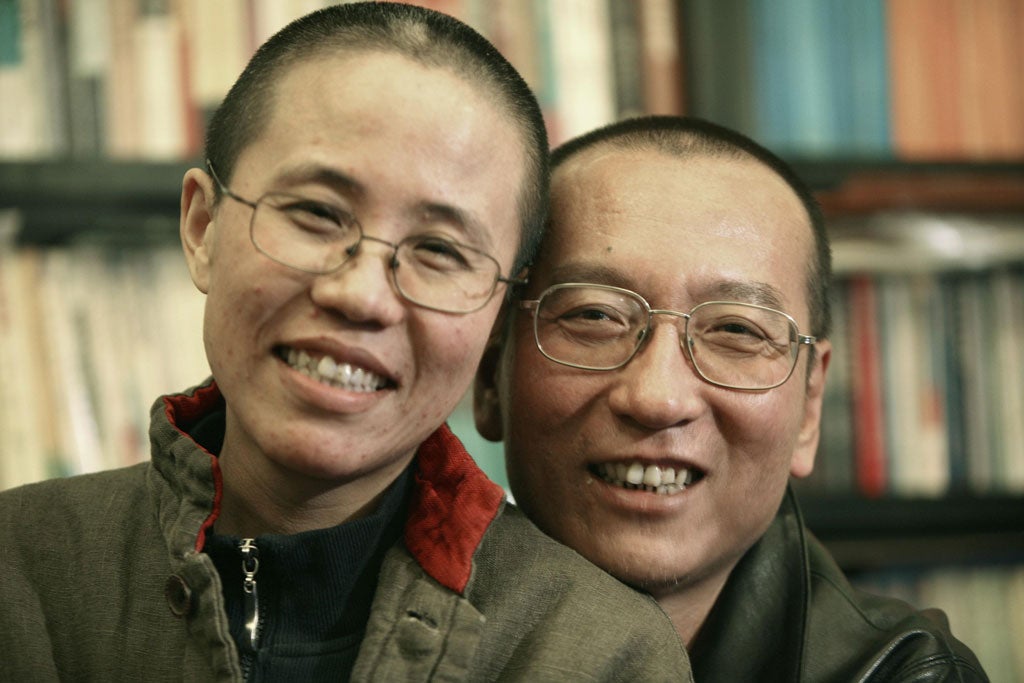

Your support makes all the difference.When Liu Xiaobo, the Chinese poet and activist, was told by his wife that he had been awarded the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize, he wept. The prize, he said, would be dedicated to the many who had fallen during the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre.

Liu, who is 56, never got the chance to make any such public declaration at the ceremony, held in Oslo. The Laureate languished in a state prison, where he continues to serve an 11-year-sentence for "incitement to subvert state power". His wife Liu Xia was - and remains – under strict house arrest. Friends, fellow-dissidents, and writers were either arrested or intimidated into staying at home. In an act that largely backfired, China attempted to bully diplomats into boycotting the event.

Liu became one of just five recipients in the prize's 100-plus year history who did not attend the ceremony. As the first Chinese citizen living in China to win the Nobel Prize, the author is heralded worldwide for his preachings on non-violent reform. His role as a key organiser behind the online democracy manifesto Charter 08 was cited as evidence at his trial. To the Party, he is a dangerous dissident and national headache.

The abiding image of Liu Xiaobo remains that of the Nobel Prize medal sitting on a vacant chair. The words "empty chair" (swiftly blocked on the web) have became synonymous in China with one man's struggle against a formidable authoritarian regime. And by forbidding Liu to collect his prize, the government has transformed him from an activist of relative obscurity to perhaps the most globally recognised emblem for human rights in China today.

No Enemies, No Hatred marks the inaugural English-language collection of Liu's work. This month also sees the publication of June Fourth Elegies, which has brought together Liu's poetry in a bilingual Chinese-English edition for the first time. Both are extraordinary bodies of work. Both demonstrate the breadth - and intellectual and emotional potency - of a powerful writer and political advocate.

Tragically, Liu is most likely unaware of the publication of either book from his position behind bars. Both Link and Yang told The Independent that they have been unable to contact Liu or his wife, who is under constant surveillance. But he would surely delight at the books' historic timing.

This weekend, China is the Market Focus country for the London Book Fair. Exiled and dissident authors have predictably been left off the invite list as China pushes its cultural influence abroad. While outrage at the state-approved author line-up has led to Bei Ling, head of the Independent Chinese PEN Centre, to protest to the media, Liu's two collections provide a timely compensation. Crucially, both are sore reminders that while the Fair celebrates Chinese literature, many of the country's most outspoken writers remain locked up.

Examples are myriad. Since December last year, China has doled out increasingly harsh sentences to at least three well-known writers and activists. In January, Yu Jie, a prominent author and a close friend of Liu's, fled to the US. In a press conference in Washington DC, the 38-year-old - who is in the process of writing Liu's biography - claimed that in the days leading up to the 2010 Nobel Prize ceremony he had been ferociously beaten by plain clothes officers. Since then he and his family had lived in an "endless black hole".

Liu's own story begins in 1989 when the author - then in America - travelled back to Beijing to join the students protesting at Tiananmen Square. It was, as Liu stated in the opening line of his "Final Statement" at his most recent trial, the "major turning point" of his life. Both new collections feature - with searing immediacy – Liu's pain as a survivor.

June Fourth Elegies deals the most directly with 1989. The collection contains a forward by the Dalai Lama, followed by an "Author's Introduction: From the Tremors of a Tomb", written on the eve of the millennium. But what really speaks are the 20 elegies, all beautifully translated by the Chinese-American poet and publisher Yang.

Each elegy is an offering to the dead, penned on every consecutive anniversary of 4 June. It is a macabre ritual that Liu maintained for 22 years, until his arrest in December 2009. Meticulously recorded under each poem's title is the location of its genesis. The span ranges from a bar in Beijing to before dawn at a re-education labour camp in Dalian. This creates a palpable sense of place and time passing. Yet what sticks out is how little has changed. In an essay in No Enemies, No Hatred, Liu deplores the lack of progress, the spilled blood which has "resulted in almost no advance within this cold-blooded nation of ours".

Above all, Liu laments the many millions in China who have ignored the state's murder in return for the Party's promises of growing material comfort. Freedom, he scoffs, is "a brand-name tie", "The ease with which money/ forgives bayonets".

One memorable line calls up images of the trademark sardonic smile mass-produced in celebrity artist Yue Minjun's paintings: "Everyone's smile is so pure/ flashing a Renminbi lustre". Yue's self-portraits have made him rich; yet in his 1989-inspired oil painting "Execution", the four men grinning in their underpants on death row smile down on a conspicuously shallow, empty world.

But if Liu's poems contain anger, they can also contain tenderness for a vision of a different world. An abiding image is of a young girl crushed like an insect. Liu mourns for "a different spring", in which he imagines the girl walking across the city square hand in hand with her boyfriend. This quiet activism - of altered lives imagined, and altered outcomes for the dead - is far more powerful than chest-beating militancy.

No Enemies, No Hatred contains a handful of Liu's poems combined with his academic essays and speeches, and documents (including the evidence used against him). The volume - which is the work of 13 translators - is a wonderful introduction to Liu's work. Liu writes with ease and persuasiveness on subjects ranging from land grabs of farmland by corrupt officials, to child slavery, to Confucius.

He has a knack for nailing contemporary China. Liu describes the country's numbed social sympathies: "No one cares for an old man who falls down sick in the street; no one tries to rescue a peasant girl who slips and falls into the river". Such observations - although written years earlier in 2004 – will resonate with anyone living in China. Last year saw the Yueyue scandal, in which a toddler was run over twice and then ignored by 18 passers-by as she lay dying on a public street.

Binding this – and both books – together is continual, self-abasing guilt. From Qincheng Prison Liu "betrayed the blood of the departed" by writing a confession. It plagues his conscience. "What have I ever done for the massacre victims?" he asks.

It is this penetrating sense of helplessness - at his own abilities to enact change, his elite status as one of the better-known activists, and about China's future - that leaves the deepest impression. This, on some level, is combatted by Liu's deep love for his wife Liu Xia, which shines through in poems dedicated to her included in both books. "Abandon the imagined martyrs/ I long to lie at your feet," he implores. In the original Chinese version of June Fourth Elegies, printed in Hong Kong, Liu Xia included her own artwork: one plate featured a disquieting black-and-white photograph of a bound doll sitting before an open book. Such an image reminds one why – at least for now – Liu will not stop.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments