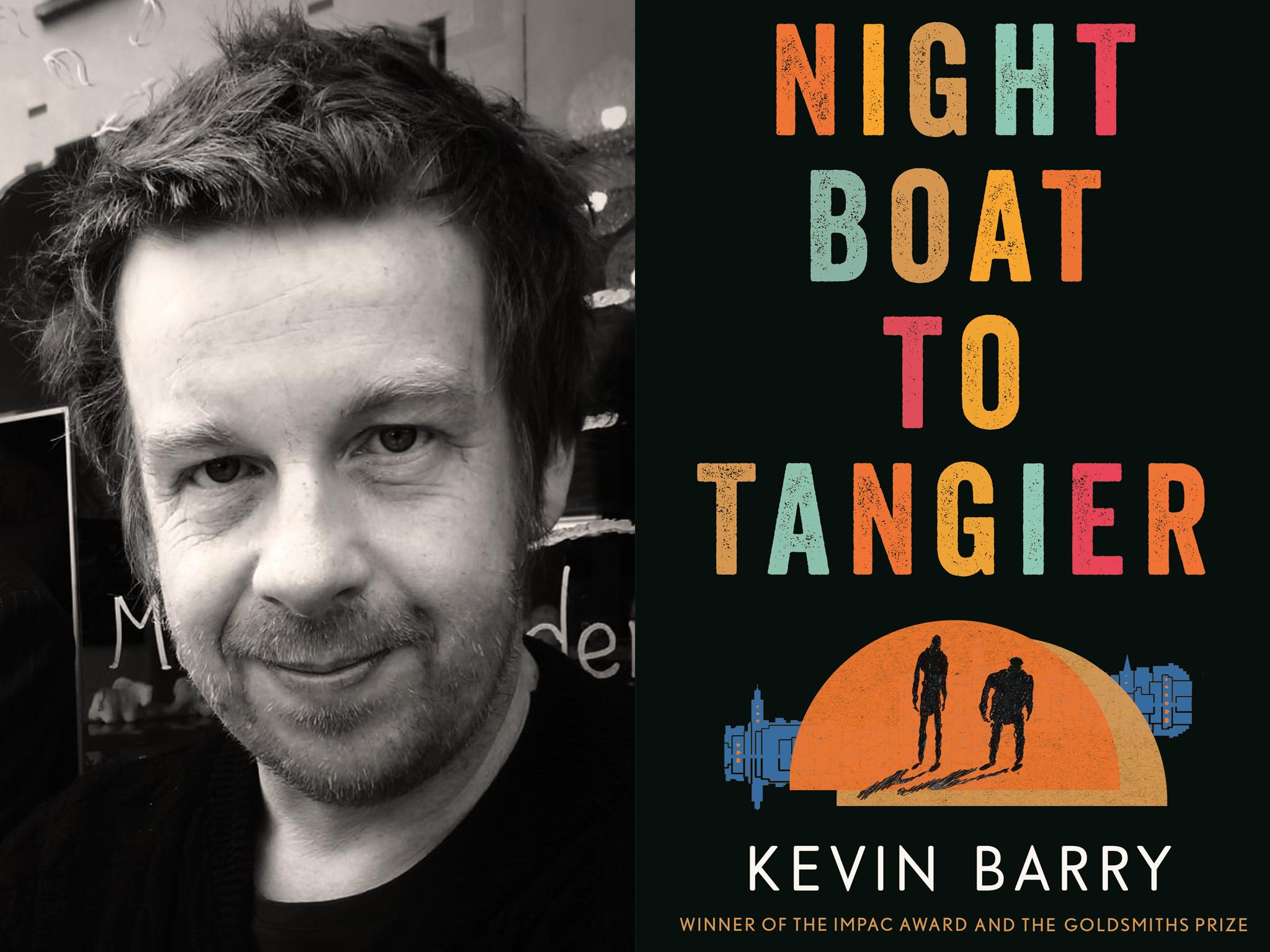

Night Boat to Tangier by Kevin Barry, book review: Captures male friendship with rare brilliance

As two Irish gangsters sit in the port of Algeciras waiting for a 23-year old named Dilly, their vaudevillian patter reminds you of Didi and Gogo in Beckett’s ‘Waiting for Godot’

Two ageing, fading Irish gangsters sit in the port of Algeciras, watching and waiting for 23-year-old named Dilly, who they believe to be heading by ferry from Spain to Morocco. Actually, scrap that – there’s nothing faded about Maurice Hearne and Charlie Redman. They are painted in vivid colour by Kevin Barry, a writer who captures male friendship – how it can be cut with rivalry and fear, but run with real love – with rare brilliance.

And Maurice and Charlie are a right pair, a double act, partners in crime. Keepers and destroyers of each other’s hearts and memories. They still dress nattily. One has a limp; the other is missing an eye.

As the night passes in this liminal place – this grotty, dicey, waiting place, “a place in which time passes almost audibly” – the pair discuss their pasts, in blackly comic chat which passes from banal to loaded on an almost line-by-line basis. They reminisce, but they also menace: any poor young crusty with dreadlocks who passes through Algeciras is liable to be interrogated by the men about whether or not they’ve seen Dilly – Maurice’s lost daughter, it transpires.

The pair’s vaudevillian patter, dancing back and forth with an irrepressibly buoyant Irish rhythm, reminds you of Didi and Gogo in Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, while their gleefully ominous threats of violence bristle off the page in a way that recalls Harold Pinter or Martin McDonagh.

But Barry – whose last novel, the gloriously strange Beatlebone, won the Goldsmiths Prize – doesn’t just traffic in nifty dialogue and gratuitous nastiness (although there are startlingly abrupt revelations in Night Boat). This story has heart too: in flashes back throughout Maurice’s life, we see how he got into smuggling hash from Morocco, laundering his profits through property in Ireland, living in Spain and – most importantly – his drink-sodden and heroin-raddled love affair with Dilly’s ma, Cynthia (“breakfast from the bottle and elevenses off the mirror”).

Barry’s own twisting, inviting authorial voice seems to lean on our shoulder, to guide us through: “It is a tremendously Hibernian dilemma – a broken family, lost love, all the melancholy rest of it – and a Hibernian easement for it is suggested: f**k it, we’ll go for an old drink.”

Within this generously spaced novel of restless short paragraphs, such sections at times skate and scurry through the years, rather than digging deep. But there is also a gorgeous wooziness, and soft-boiled vulnerability, to some of Maurice’s memories, as well as the acute, sour sharpness of lust and jealousy, paranoia and self-loathing. And the more you find out about Maurice, the more you find out too just how intertwined he is with Charlie Redmond.

Barry’s descriptions are often startlingly good. He slides words and images across one another, to create some new, precise image: Maurice and Charlie’s smiles are “high and piratical; their jauntiness has a cutlass edge”. Perfect.

There’s a fair amount of anthropomorphising the elements to reflect characters emotional states: when Maurice recalls falling in love with Cynthia, he recalls the static on her hair, how “even the air was excitable around her”. When it all goes wrong, there are “hysterical sunsets”, and the sea’s “moans” prove she’s cheating on him. Occasionally such imagery is overwrought or overstretched (“a cold white moon speaks highly of the coming winter” doesn’t quite convince, for instance) but in general, it’s a fair price to pay.

And although Spain springs to life, it is Ireland that most strongly casts a spell: “Its smiling speaking rocks. Its haunted field. Its sea memory.” Indeed, the novel is gently woven through with a kind of magic. Maurice comes to believe he’s struck by “bad luck” for building new houses on an old fairy fort. Dilly embraces white magic to deal with her grief, while one of Maurice’s other old flames tried to cast evil spells on him. All this is met with scepticism – the book doesn’t cloy with stereotyped Irish folklore, thank god – but it does lend a shivery undercurrent. Or at least, a sense of how, in hard times, we inevitably seek explanations beyond our own human fallibility, and solutions beyond our own human limitations.

'Night Boat to Tangier' by Kevin Barry is published by Canongate, £14.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks