Munnu: A boy from Kashmir by Malik Sajad, book review: A habitat under threat

The oppressed are depicted as endangered deer in this remarkable graphic novel

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A remarkable and important graphic novel, Munnu offers an alternative history of Indian administered Kashmir, specifically Srinagar, drawing on the author's life to tell the story of Munnu as he grows up to become Sajad.

Militarisation and resistance is much more than the backdrop of Munnu's life; it weaves into every aspect of his existence. Art is a source of pleasure for young Munnu; he teaches himself to draw the chinar leaf and the "curves of the paisley". But there is little chance of retaining innocence under occupation, "sketching the photos of unrecognisable, disfigured people from the newspapers," Munnu tells us. The first image that he masters – gaining popularity among his friends – is an AK-47.

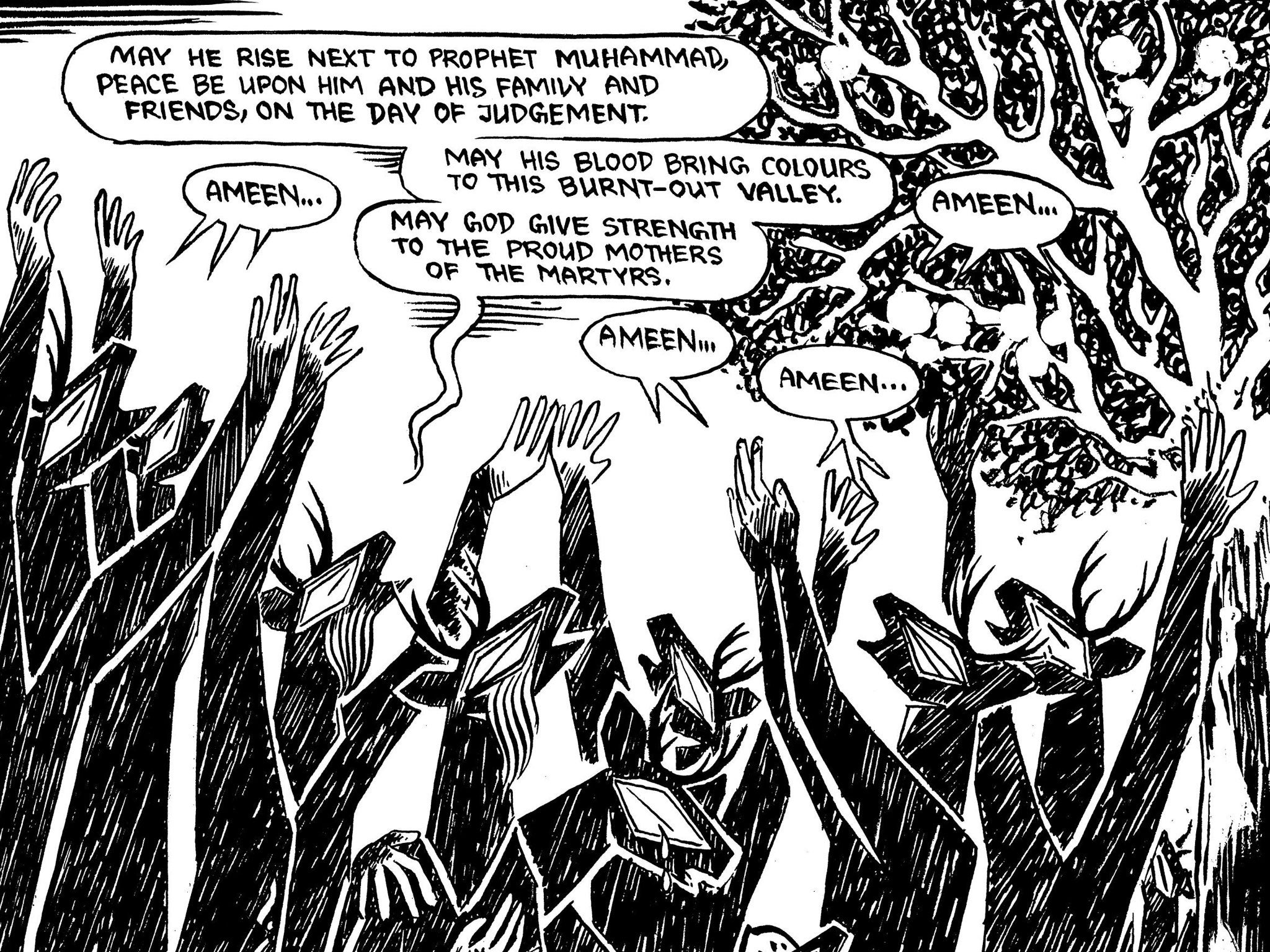

Like the author, Munnu becomes a political cartoonist, using art to "criticise, express, expose, to seek revenge". The author brings his experience to Munnu in fruitful ways; a nuanced reflection of the politics of life under occupation, though the novel does take the side of the Kashmiris who deal with daily brutality and restriction. These Kashmiris are represented as deer, while everyone else is human. It seems an odd decision initially; we struggle to distinguish between characters. Sajad's father is a woodcut printer, and there is the impression in the novel of woodblock printing. As deer, they are not individualised and appear expressionless when they gather in schools, protests, identification parades and crackdowns.

We find out later that these are hangul deer (the Kashmir stag) which are now endangered, since their habitat is being destroyed by the army. And while they might be generic visually, each of the characters is strong and three-dimensional. We are struck most of all by the love between them, especially Munnu's relationship with his family. The author refuses to represent Kashmiris as victims. Flicking through someone else's graphic novel, Munno observes: "The characters in this book look like they're born to suffer… they look like they're crying." The use of deer evokes Spiegelman's Maus, which represented the dehumanisation of Jews by the Nazis in the form of mice. Munnu sets out to contribute to the burgeoning field of graphic novels about "conflict zones", to tell the world about Kashmir. Yet this is not without internal struggle with the way that the "world" needs you to represent yourself. When it is suggested that he should use the word intifada in the title of his book, to connect to better-known struggles, the narrator's instinct is to resist; theirs is a specific situation, not a generic "struggle".

While seeking to communicate with the "world", Munnu does not erase the role of this "world" in creating Kashmir. "You mean British people don't know that the British government sold each Kashmiri for 2.5rs?" says the narrator (Colonial Britain sold Kashmir to ally Maharaja Gulab Singh).

We are struck by the aggression of "brother", a Kashmiri journalist who lives in Delhi and seems to have internalised an elite way of being. Ruthless and insensitive, he teaches Munnu how to conduct a "professional" interview. There is the arrogance and entitlement of an American artist, Paisley, who lands in Kashmir to make a film and treats Munnu as a tour guide. It is testimony to the skill of this debut work – penned by a 25-year-old – that, while Munnu seems uncritical of these characters, we see their ugly side.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments