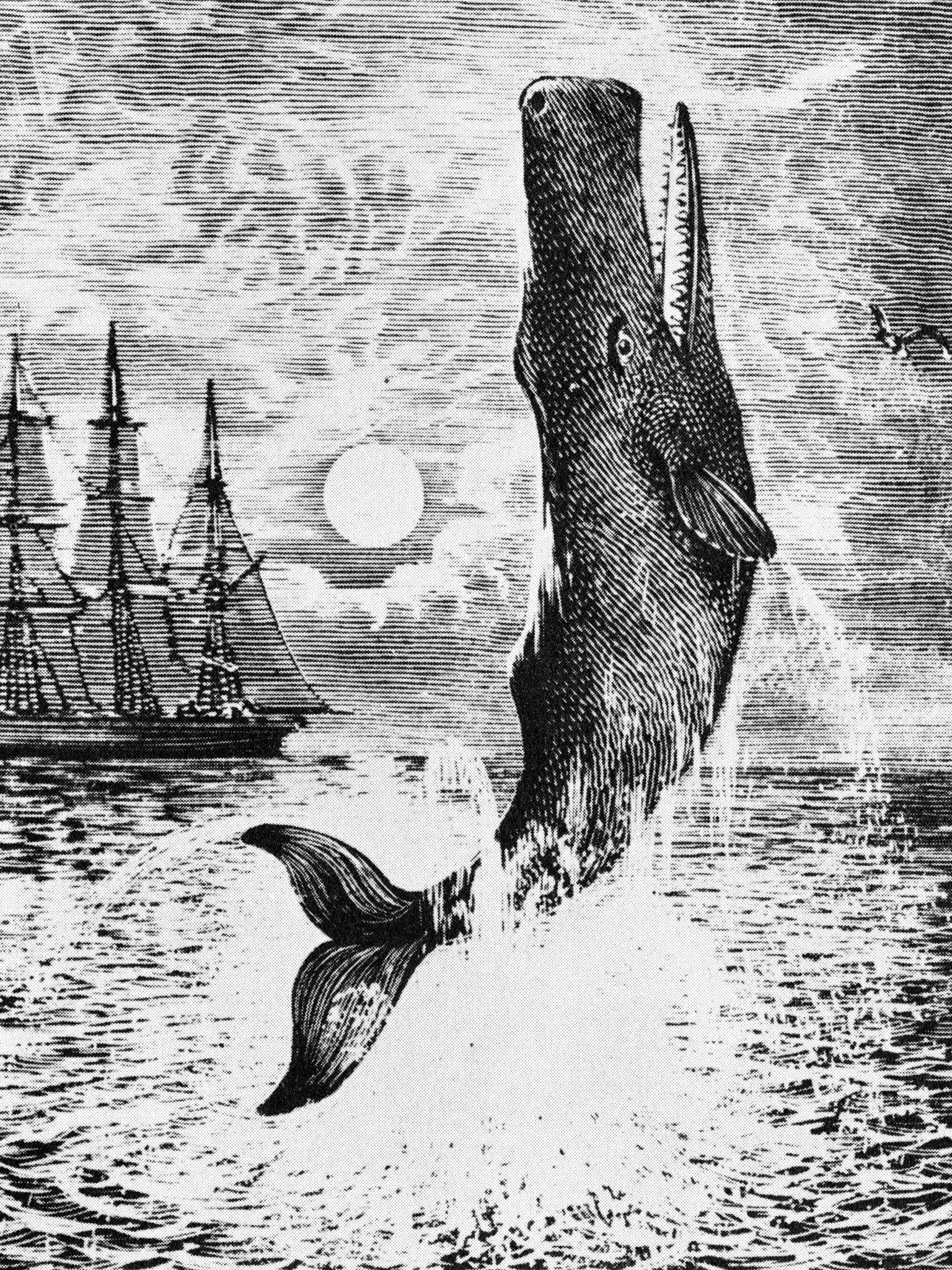

Moby Dick by Herman Melville, book of a lifetime: A playful, experimental novel

In writing a high tragedy about a whaling voyage, Melville is emulating and paying tribute to Shakespeare and the larger literary tradition, but he's also revising and Americanising it

"A whale-ship was my Yale College and my Harvard." That's Ishmael, the narrator, speaking, but it could easily be Herman Melville himself. Melville left school at 12 and never attended college. He was 29, and had already published two successful travel books, before he read Shakespeare or Milton. When you read this great, bamboozling novel it is helpful to remember that it is the work of late-blooming autodidact, suddenly desperate to get in on the literary action.

I'm no autodidact myself (for my sins, I've spent almost all my adult life in or around university English departments), but I imagine that one of the advantages of being one is that it doesn't feel very traditional or fixed – it feels new, and it feels like something that can be altered and played around with. Moby Dick is a playful, experimental novel (which is why, having been neglected on publication, it was championed and made famous in the era of modernism) it's also deeply democratic in its themes and its methods.

In Chapter 26, Melville invokes the muse-like Spirit of Equality to justify his decision to ascribe high qualities and tragic grace to the "meanest mariners and renegades and castaways". In writing a high tragedy about a whaling voyage Melville is emulating and paying tribute to Shakespeare and the larger literary tradition, but he's also revising and Americanising it at the same time. (In Shakespeare, of course, the workers are mainly there for comic relief).

There is an autodidactic bolshiness to that revisionist move which is still impressive and which gives this great novel much of its energy and grandeur. But now, 124 years after his death, Melville has himself become part of the literary canon. A fixture. And reading Moby Dick can sometimes feel a bit dutiful, like climbing the spiral staircase of some great American monument. Time then, perhaps, to revise the reviser. That is what I've done, or tried to do, in my new novel The North Water. Revising Moby Dick may seem like the height of authorial hubris, but then hubris is what Moby Dick is all about – the hubris of Ahab, and also the hubris of Melville. To alter and reimagine it is, in that sense, only to follow its remarkable lead.

Ian McGuire's 'The North Water' is published by Scribner

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks