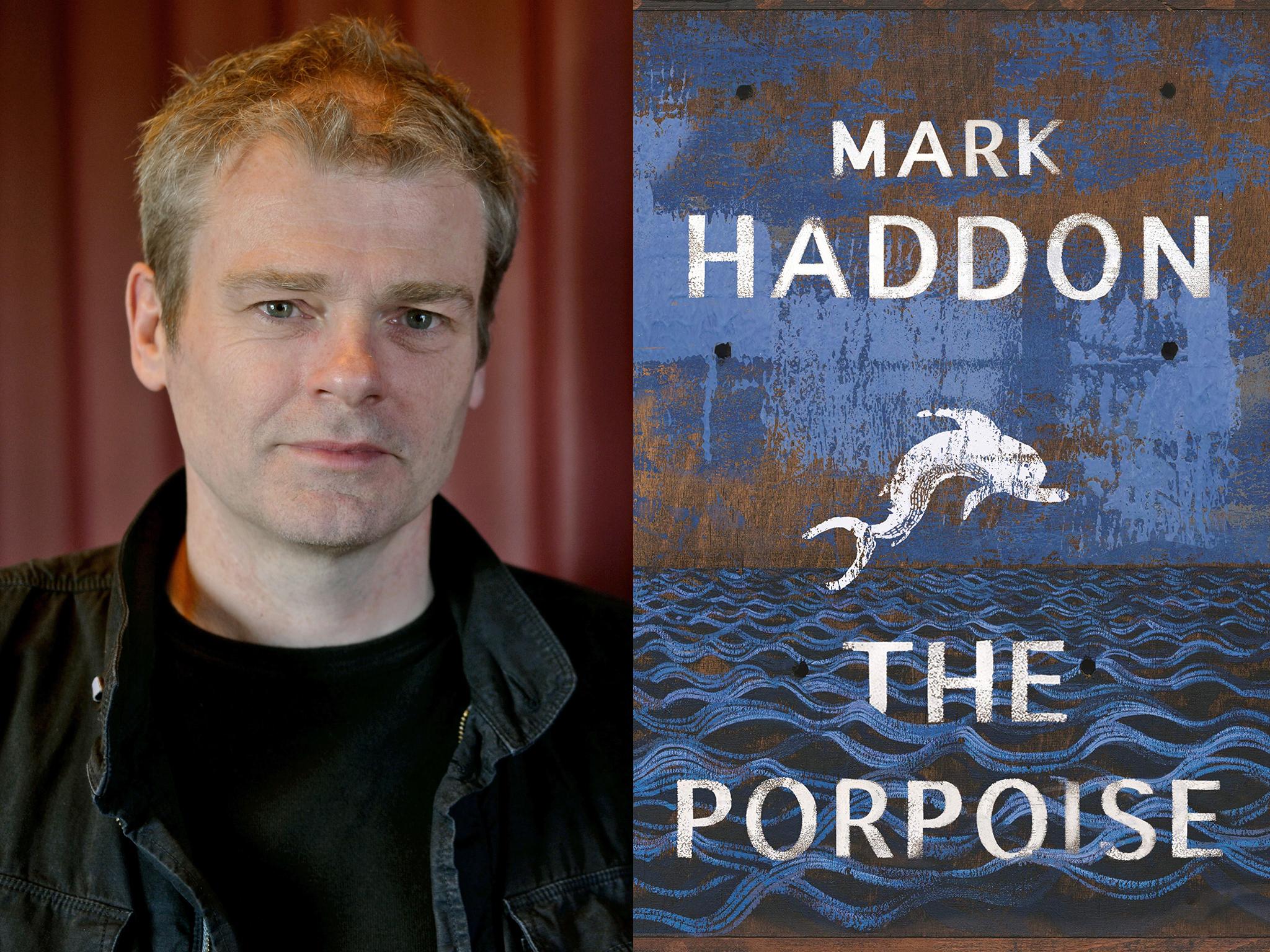

Mark Haddon’s The Porpoise, review: ‘A glittering tapestry of a novel’

Haddon’s latest book powerfully reworks Shakespeare’s play ‘Pericles’, about the King of Antioch and his incestuous relationship with his daughter, propelling it into the modern day

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.William Shakespeare’s Pericles is not one of his most-loved, or even performed, plays, and in any case was probably only half written by him (the first part is thought to have been composed by George Wilkins, a minor figure who was, to say the least, rather unpleasant). But it has now been the inspiration for not only Ali Smith’s Spring last month but now also Mark Haddon’s The Porpoise.

Haddon’s glittering tapestry of a novel skilfully redeploys the structures of Pericles’ source material. In the play, the King of Antioch is having an incestuous relationship with his daughter; this is transmuted into Philippe, a fabulously wealthy aristocrat who, having lost his wife in a terrifying plane accident (which begins the book in hair-raising style), fixates upon the daughter, Angelica, literally torn from her mother and the wreckage. This first part is handled beautifully, the tension and horror of Philippe’s abuse set starkly against the comfort and security of their international milieu. Angelica becomes a kind of fairy tale princess, imprisoned by an ogre, growing up in isolation that only uber-wealth can afford.

Rescue appears to come in the form of Darius, a handsome, apparently effete art dealer’s son, who comes out of curiosity on the pretext of selling some rare prints. Angelica immediately falls for him, but the results are catastrophic.

Here the book takes an intriguing turn, as Angelica, cut off from all aid, begins to elaborate a fantasy world of her own, in order to provide a psychological escape from her abuser. The book is in part about trapped women – Angelica’s mother; Angelica herself, within the gilded walls of her father’s mansion; Chloe, a princess, thought dead, cast into the sea, as well as her daughter Marina, whose life is under threat from an adopted mother. There’s also an intriguing couple of chapters about George Wilkins, in which he is made to face up to all the women he’s injured during his life.

Darius becomes Pericles, Prince of Tyre, and Angelica invests his narrative with the resonances of myth, but also with vivid sensory information. Sails creak, spices scent the air, as Pericles must escape the assassins sent on his trail, before undergoing many travails. Quite how much of the story reflects the level of Angelica’s reality is left unclear: in her own world, she first stops speaking, refusing her father’s advances, then stops eating. Her fate becomes intertwined with all the many women in her stories: abused, beaten, yet providing fantasies of escape and power. One of the central myths of the book is that of Diana and Actaeon, in which Actaeon is cruelly punished for catching sight of the goddess bathing: the chaste huntress looms large, giving power to women everywhere.

The sea is the strongest metaphor in the novel, surging and changing, providing life and death, and becoming an agent of the marvellous. Shakespeare’s late romances are all about those coincidences and supernatural effects which can seem, on stage and on the page, ridiculous. They do, however, indicate the agency of divine providence.

In The Porpoise, Haddon gives voice to a character who, in Shakespeare, receives no more than a passing mention, and in doing so, shows the transcendent power of stories to heal and restore.

The Porpoise by Mark Haddon is published by Chatto and Windus, £18.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments