Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

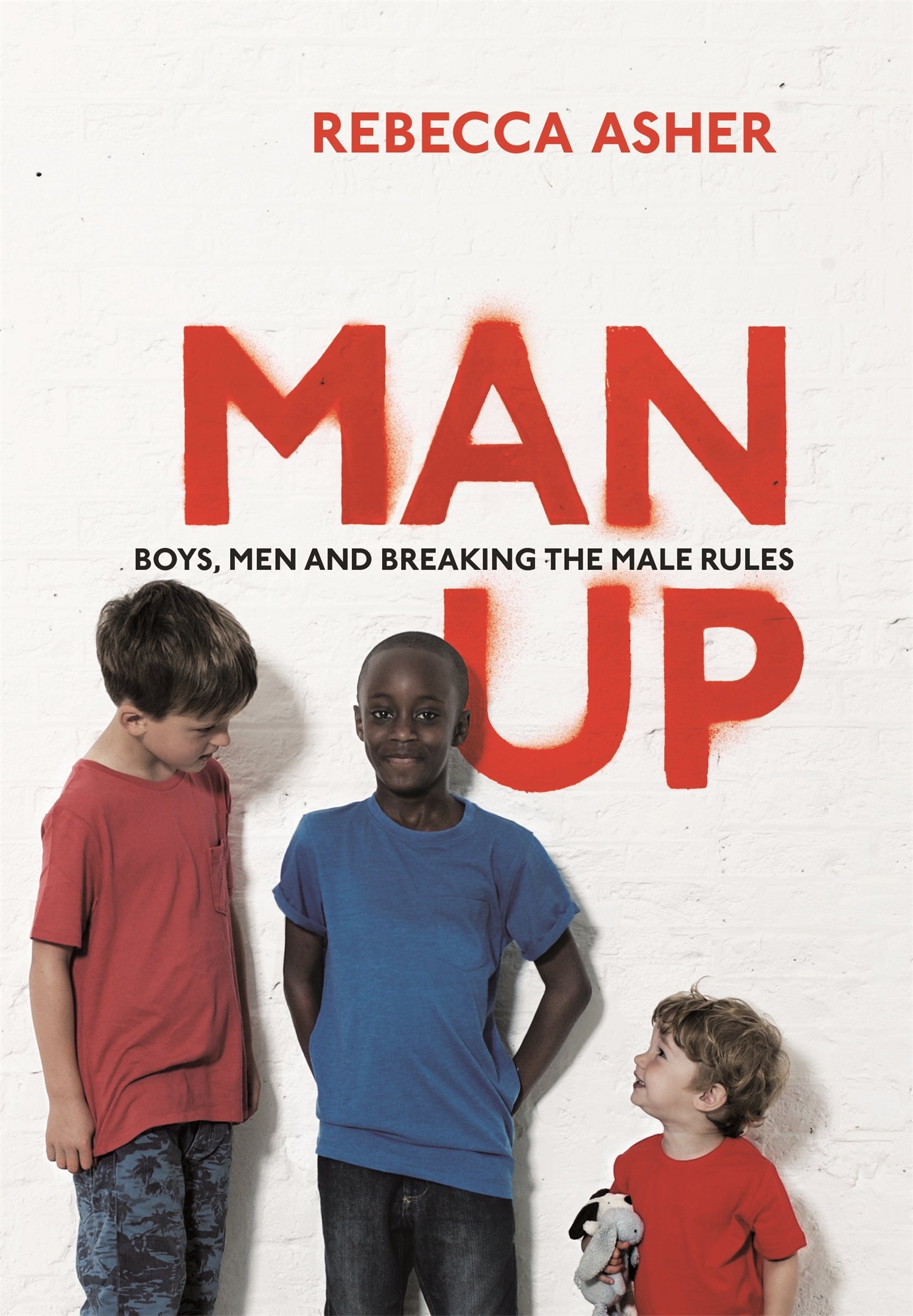

Your support makes all the difference.At the beginning of this study of 21st-century men and boys, Rebecca Asher writes: “I am entering choppy waters, as a woman commenting on the state of men.” But, as Asher demonstrates, the way we raise boys and treat men affects everybody, so it’s timely and necessary for her to explore whether contemporary Britain really is witnessing a crisis of masculinity. Asher’s conclusions – that sex education should be statutory in schools, that fathers should be closely involved in raising their children and gender stereotypes should be overturned – sound like common sense. What’s shocking is that society perpetuates “poisonous concepts of masculinity and femininity” which restrict us all.

It’s two decades since I stood in the playground, amid the daily barrage of insults, posturing, fighting, but I still know exactly what a man in his twenties means when he tells Asher school was “a culture of conform or die.” Gendering, though, begins earlier with children’s clothes, toys and stories reinforcing the traditional roles to which boys and girls should aspire. We’re obsessed, Asher believes, with “biological differences between the sexes” and some parents she interviews lazily say their sons are “less complicated” than their daughters. This plays into a “feedback loop of gendered behaviour and expectations”, at the heart of which lies the idea that boys suppress their feelings.

Across the social spectrum, the effects are devastating. Asher interviews young gang members, many of whom are excluded from school and destined for prison. She rails against “myths about boys’ inbuilt reading aversion”, examines the rise of misogyny on university campuses and loneliness among older men. She exposes the agendas of men’s rights activists for what they are – anti-feminist, stupid, fearful – by emphasising “the central role that domineering, aggressive masculinity plays in violence.” Her book is populated by thoughtful interviewees, many of whom are trying to change things: the “Let Toys be Toys” pressure group, the charities Carney’s Community, which works with disadvantaged youths, and CALM, which aims to reduce the alarming number of male suicides, are doing important work.

Increased paternity leave, Asher claims, would free fathers to forge stronger bonds with their children and let mothers pursue their careers, although her view of the more generous Scandinavian systems sounds a little rose-tinted. “Workplace jostling” is blamed for men’s reluctance to request more leave but it’s odd that Asher doesn’t identify our wider fixation on competitiveness as a factor here. Nevertheless, the message is consistent: “Women will not be free of patriarchal oppression until men stop oppressing women, and men will not stop oppressing women until they themselves are free from patriarchy.”

Sometimes, wide-ranging, statistics-packed books like this one run the risk of reducing individuals to types and numbers. As a married, childless, self-employed, male feminist, who enjoys reading, cries often and was once excluded from school, I’m not always certain how Asher’s discussions apply to me. But that, in a way, is her point: we should all be free to be ourselves and, rather than redefining masculinity, we will be happier if we abandon the concept altogether.

Harvill Secker, £14.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments