Magna Carta, The True Story Behind the Charter by David Starkey, book review

Starkey shows Magna Carta's resonance, but fails when it comes to the modern day

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Like most children of the 1960s, I learned a certain version of Magna Carta. History back then was little more than a roll call of kings and queens – good, bad and indifferent – and the most cartoonishly bad of the lot was King John, who appeared to spend all his days thinking of new ways to terrorise everyone.

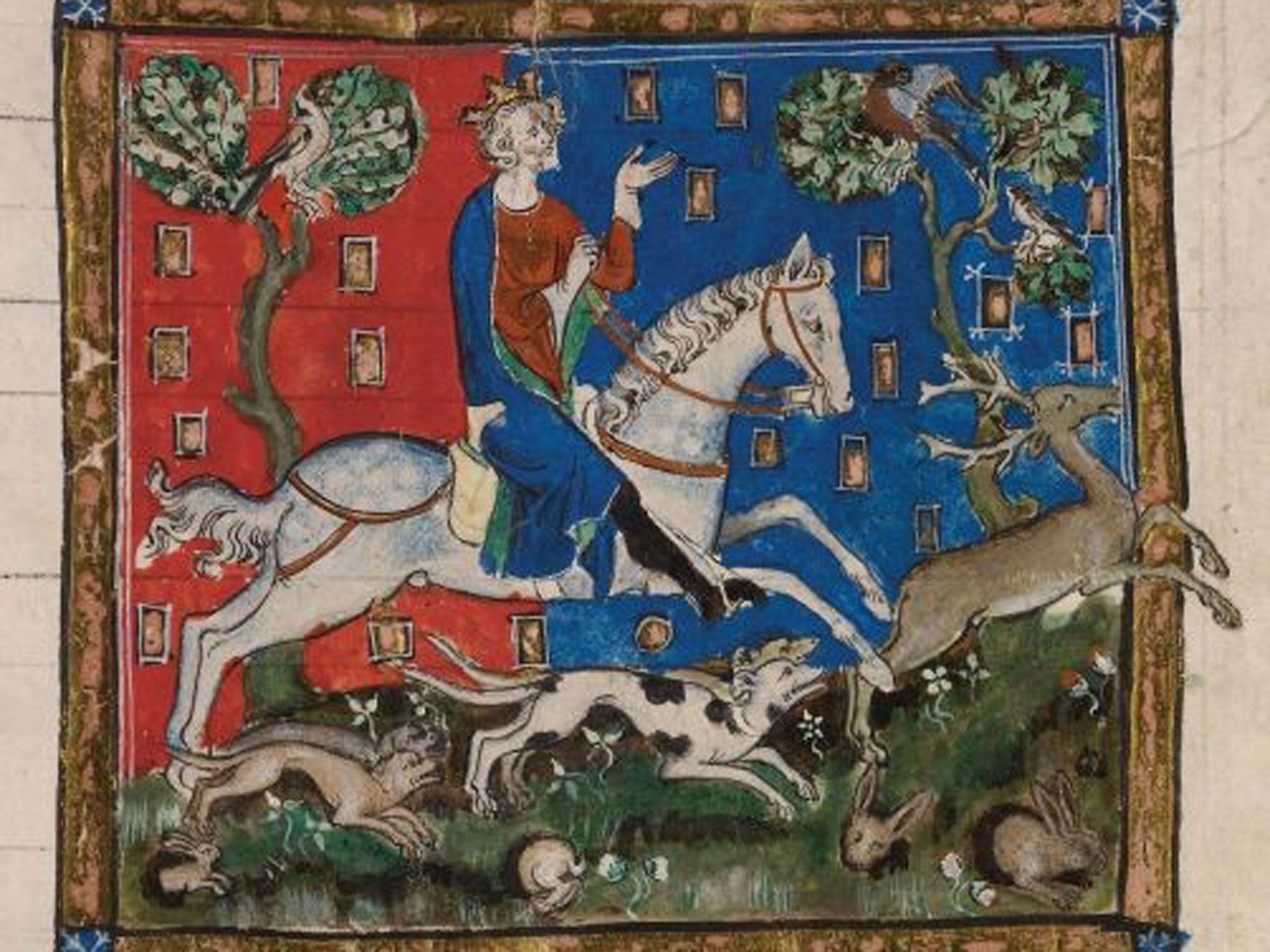

As a result, the barons under William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, dragged John off to an evocatively named place called Runnymede and made him sign up to a Great Charter of liberties. In a nutshell, he had to agree to lay off the Church and the City of London, let people be tried by their peers and stop grabbing people's property. England became free and everyone said hooray and went home.

I am grateful to Dr Starkey for reminding me that while hurtling through this complex subject en route to the Battle of Crecy, my harassed teachers actually got the Magna Carta right more or less. It is easy to laugh at the more arcane bits of an 800-year-old treaty, especially at those clauses about cleaning fish weirs in the Medway, repairing bridges and what to do with Welsh prisoners.

Most of the 61 chapters, which Dr Starkey helpfully includes at the back, are of little interest now to anyone except medievalists. But the barons were practical men of their time, not constitutional lawyers, and the political implications of some of their demands still sound extraordinarily forward-looking. These are the clauses, as Dr Starkey says, which "resonate through the ages".

If England after 1215 moved off in one direction, towards the idea of government operating by law while tsarist Russia and indeed France went off in another direction entirely, towards government by decree, it is partly because Magna Carta established or at least confirmed some enduring ideas about the just limits of executive power.

As a historian of the right, Starkey is keen to ram home a couple of Conservative-ish points about the events of those tumultuous years, unfavourably comparing the more radical document put forward to John in 2015 with the what he sees as the more truly English, consensual version that was re-issued under John's son. Whether or not one accept his interpretation, he is right to assert that the first Magna Carta might well have sunk without trace had it not been toned down to the point where the crown could live with its provisions.

Dr Starkey is far less persuasive when he argues at the end of the book that, at a time when the British state appears to be fragmenting, we could do with another William Marshal. In what sense? The problem in 1215 was the over-concentration of power in the hands of one man.

The problem today is that no one seems to know any longer where power actually lies. We do not know whether it is to be found in our own parliament and courts, in Brussels, in multi-national corporations, or perhaps even in such phenomena as Google. It is this development – the dispersal of authority in so many different directions – that underpins the complaint that voting has become almost pointless because the result won't make a difference. How a new charter of liberties will solve any of that, I fail to see.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments