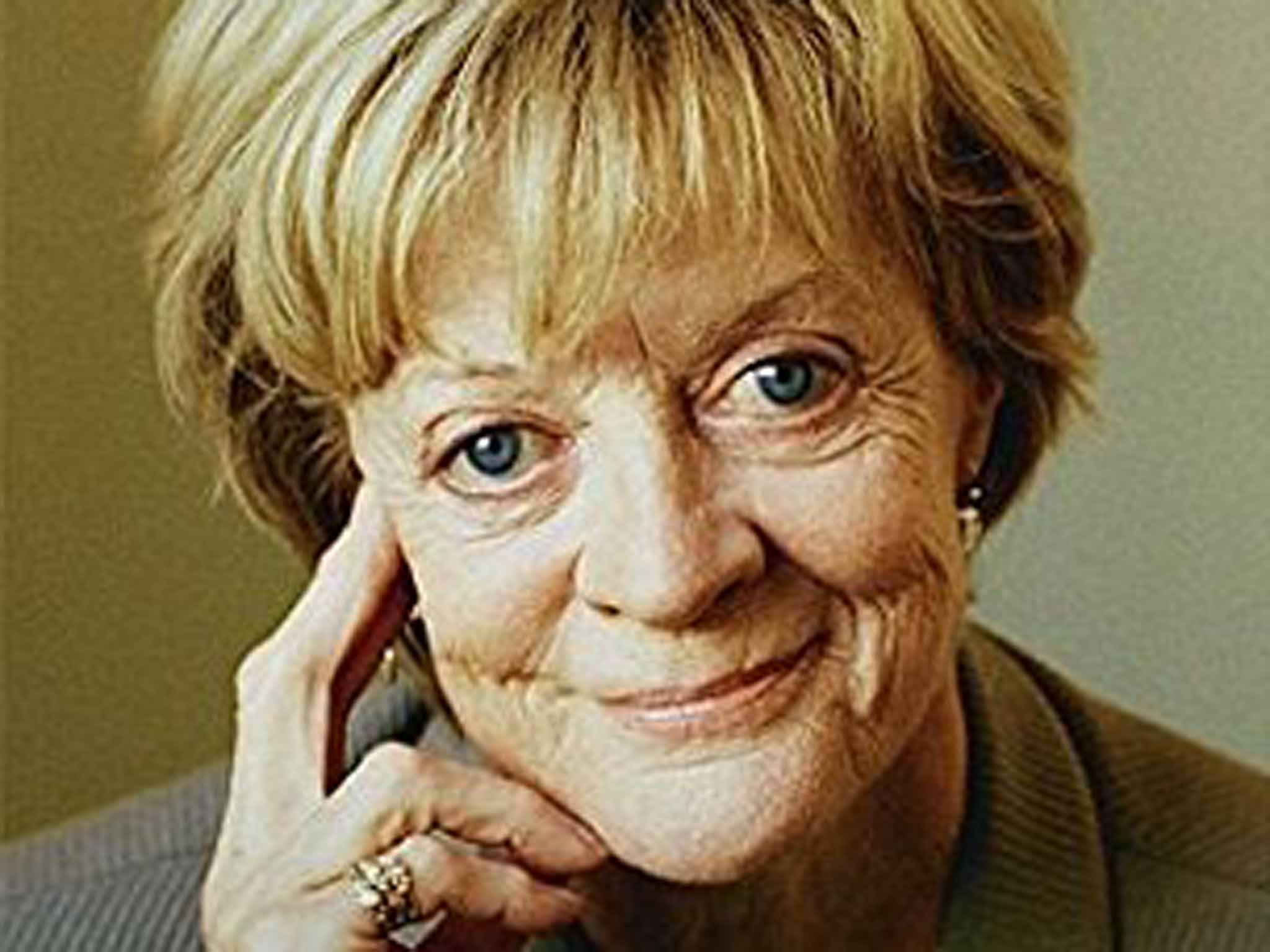

Maggie Smith: A Biography, by Michael Coveney: The facts are all here, yet she remains an enigmatic figure

Dame Maggie, the dowager of discretion

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In his epilogue, Michael Coveney reveals that when he first proposed a biography to the famously publicity-averse Dame Maggie Smith, she seemed horrified by the idea, exclaiming: “Ooh, how absolutely ghastly. How absolutely awful. I can't think of anything worse… Ooh, but there's nothing to write about… I haven't done anything. I don't know what it is I do.”

That said, during a subsequent conversation she invited him backstage after a Broadway matinee performance of Peter Shaffer's Lettice and Lovage. At that meeting, while still appearing resistant to the idea of the book, she gave him the telephone number of her then husband Beverley Cross, who she would “warn”' to expect a call. When Coveney, a critic, spoke to Cross, the latter was encouraging.

All this took place in the early Nineties in preparation for a previous edition of this book, but it remains one of the sprightliest and most revelatory passages, since, suddenly, Smith is not being reported at a second-hand distance but is there on the telephone and in a dressing room. Generally she seems to have treated Coveney as one might expect her Downton Abbey character, the Dowager Countess of Grantham, to respond to the clamour of a more intrusive age: as something to be kept at arm's length and endured rather than encouraged.

Most of the information here seems sourced at one remove – from siblings, colleagues, husbands (she was married to the actor Robert Stephens before Cross), her two sons by Stephens (the actors Toby Stephens and Chris Larkin) and an archive of memorabilia built by her adoring father.

The facts are all here, yet Smith remains an enigmatic figure. There is none of the blistering revelation and insight into the near past that we have come to expect from the best contemporary memoirs and biographies. Instead, this should be regarded as a critical appreciation. Coveney seems more interested in recounting the roles Smith played and their reception than in writing about her private life.

There are hints that Smith, who was born in Ilford, Essex, to aspirational lower-middle-class parents but raised in Oxford, where her father worked as a university lab technician, had a remote relationship with her dour Scottish mother. There are also suggestions that at times she regretted her career meant long stretches away from her sons. But these are small conjectures in what is a solid and admiring portrait of a beloved actor's craft and career. Whatever it is that Smith does, or why, remains something of a mystery.

Weidenfeld & Nicolson £20. Order for £16.50 (free p&p) from the Independent Bookshop: 08430 600 030

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments