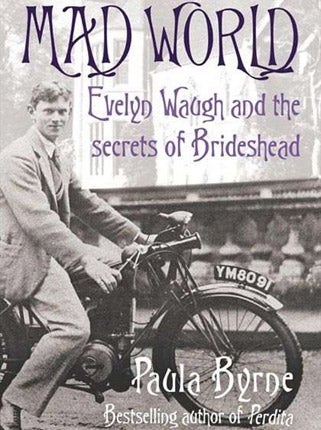

Mad World, By Paula Byrne

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Might we have revisited Brideshead Revisited too much? The past six years have seen a miscast Hollywood adaptation, Michael Johnston's unloved sequel Brideshead Regained, plus Jane Mulvagh's Madresfield, a 500-page investigation into links between the novel and Evelyn Waugh's association with an unstable family of idiosyncratic aristocrats, the Lygons, and their seat, "Madders".

Paula Byrne's Mad World is a decent, well-researched read. But it tackles precisely the same topic as Mulvagh's. We are promised new revelations as to Waugh's sexual friendships with young men at Oxford, particularly one of the putative models for Sebastian Flyte: Hugh Lygon. He exhibited the requisite childlike grace and beauty, took rooms with Waugh and drank himself to death in Flyte-like manner. Still, two gay relationships at Oxford are well documented, and adding Lygon on the say-so of notorious gossip A L Rowse may not be wise.

Byrne has trawled all possible archives assiduously. There's just not much to add to fuller portraits of Waugh's set in Martin Stannard's and Selena Hastings's lives. Given her debt to these, as well as Christopher Sykes, Waugh's first biographer, it is rather cheeky of Byrne to argue that literary biography needs liberating from "the shackles of comprehensiveness".

Waugh himself offered thumbnail, if discreet sketches of some Lygons in the 1964 memoir, A Little Learning. He wrote of a fountain's inscription in the Madresfield garden: "That day is wasted on which one has not laughed." Mary Lygon had retorted: "Well, you and I have never wasted a day, have we?"

I wonder, though, whether Waugh would now be laughing at the way his last, flawed masterpiece is progressively eclipsing the earlier comic fiction. Published in 1945, and "appalling" to its author by 1950, Brideshead was heavily rewritten, and prefaced by Waugh in 1959 as "infused with a kind of gluttony, for food and wine", for past splendours and "ornamental language " which now "with a full stomach, I find distasteful."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments