Juliet the Maniac by Juliet Escoria, review: A startlingly honest tale of mental illness and addiction

Dubbed ‘The Bell Jar’ for the modern age, this autobiographical novel about a teenager’s road to recovery from bioplar disorder and drugs, cements Escoria’s status as one of the most powerful voices in independent literature

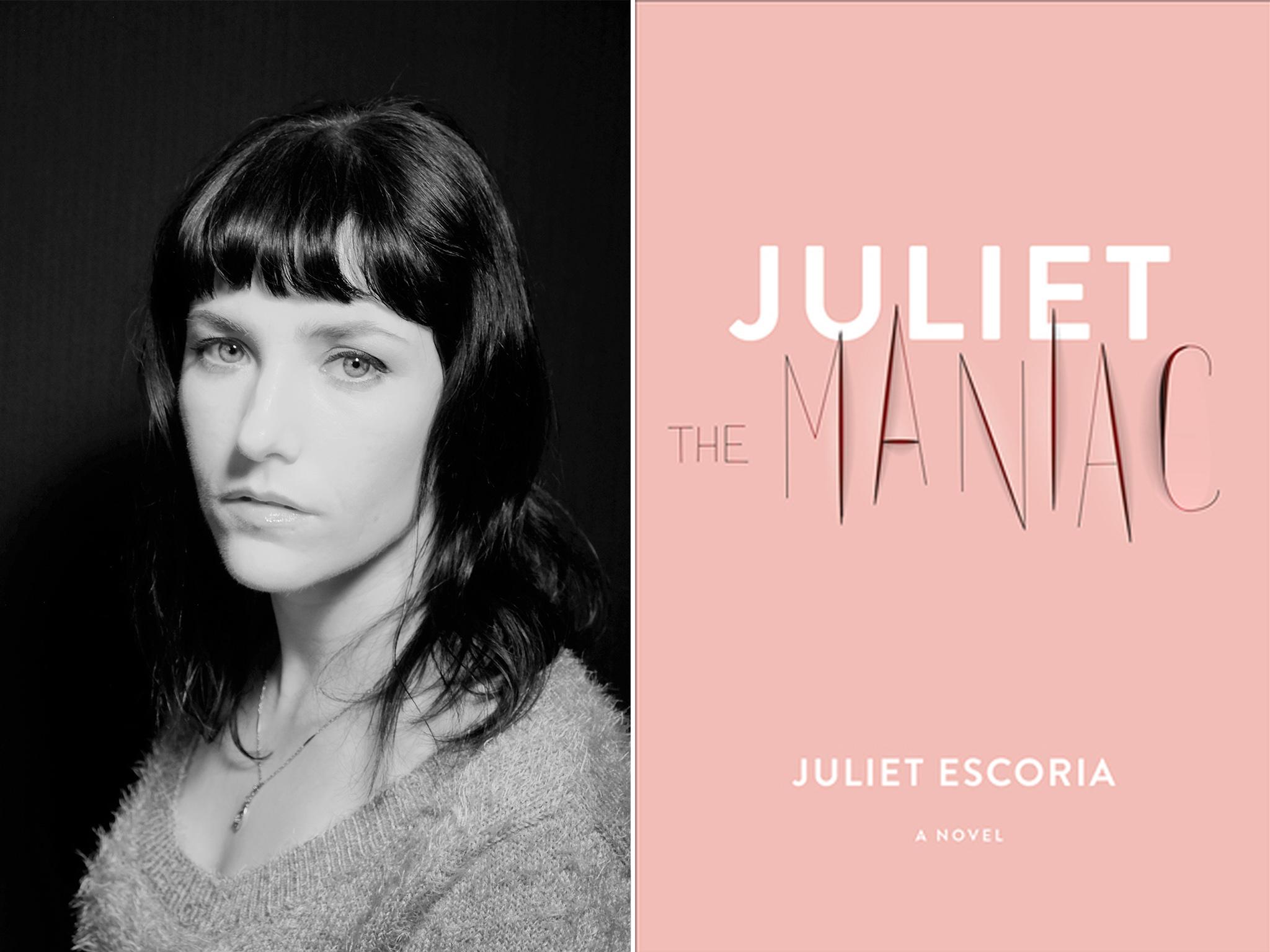

When Juliet Escoria published her first story collection, Black Cloud, in 2014, her writing was deemed “brutal”, “honest”, and “incredibly real”. Her poetry collection Witch Hunt, which followed in 2016, further demonstrated her knack for finding beauty in darkness. With Juliet the Maniac, a startlingly honest tale of mental illness and addiction that has been described as an “autobiographical novel”, Escoria cements her status as one of the most powerful voices in independent literature.

Juliet (Escoria’s fictionalized self) begins her story “the year the rock star shot himself” (presumably 1994, the year of Kurt Cobain’s death). She’s a gifted student living in California, attending honours classes that she sometimes leaves “blanketed in gold: perfect, shining, chosen” after receiving a professor’s praise. Soon, though, symptoms of her bipolar disorder begin to take over her mind. She can’t sleep. She can’t sit in class. She hears voices. There’s “something invading [her] brain and body”, “something sick inside of [her]”, a “plague of bad thoughts” that tells her she wants to die. Juliet does drugs, too, and becomes increasingly knowledgeable in the many ways one can get high.

What follows is a detailed, at times painfully real account of Juliet’s road to recovery – which is, of course, a sinuous one. Juliet’s voice is direct, unforgiving, and honest like perhaps only teenagers can be. Those qualities combine to make us feel Juliet’s isolation as she tries to get a grasp on her mind, makes empty promises to herself that she will catch up on the homework she can no longer do, and tries to tell the adults around her (her parents, a therapist) about her symptoms. After a first suicide attempt, Juliet is transferred to another school, hoping for a new beginning – but things are rarely so simple in the realm of chronic mental health issues.

Perhaps surprisingly (because the novel is built on traditionally “dark” themes), hope, or at least the determination to stoically make it to another day, is one of the driving forces behind Juliet’s narrative. Sure, it takes a while until we finally find her on what seems like a solid path to recovery (and even then, we are reminded that things are usually more complicated than they seem). But even when all Juliet can muster is resignation (as opposed to a voracious appetite for life), there is a strength in her behaviour – a reminder that sometimes, resignation can be good enough, in that it serves as a bridge to the next day. Juliet’s older self gives her perspective on occasion in beautiful “letters from the future”, providing both some reassurance as to Juliet’s destiny and an opportunity to appreciate Escoria’s talent for voices.

Juliet’s story unfolds with the Nineties as its ever-present backdrop, as the novel does for that decade what The Bell Jar and Go Ask Alice (both of which are name-checked in Escoria’s book) did for the Fifties and the Sixties respectively. There’s hemp chokers and dark brown lipstick, cargo pants and loud music on MTV. Juliet the Maniac is also, at its core, a coming-of-age novel, one that perhaps fully blossoms as its narrator experiences certain rites of passage (first love, first heartbreak, first complicated friendship). Sex is, refreshingly, treated as a kind of afterthought, with a simplicity rarely found in coming-of-age works – “My first credit card had way more of an impact in my life than losing my virginity,” says Juliet.

Escoria fully embraces the beautiful flourishes that sometimes come from the teenage mind (“The fireworks were small and far away but they were beautiful, because it turns out society is something that looks best from a distance,” Juliet muses to herself), yet her simple words and unforgiving observations mean the novel never comes close to glamourising mental health issues. Escoria’s prose cohabits with patient logs and evaluations, reminding us that while Juliet’s journey unfolds for us in beautiful words, it can also be told in the short, descriptive phrases of medical charts. Juliet’s medications are listed in full and we are privy to her prescription changes as her team tries – and sometimes fails – to figure out what treatment plan will give her the best chance at recovery.

Juliet the Maniac has justifiably been compared to Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar. It also calls to mind, structurally and tonally, the movie Beautiful Boy (itself adapted from two memoirs), in which Timothée Chalamet plays the young drug addict Nic Sheff. Both works portray the unrelenting self-destructiveness that comes with addiction (Juliet’s drive to get high is such that it often seems like second nature). Both works take us on the meandering road to sobriety, from someone’s teenage years to their adult age, from the deepest existential despair to the most dazzling flashes of hope – and both have an unnerving (but necessary) way of teaching us that as far as mental health and addiction are concerned, nothing is ever to be taken granted.

Juliet the Maniac is published by Melville House, £12.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks