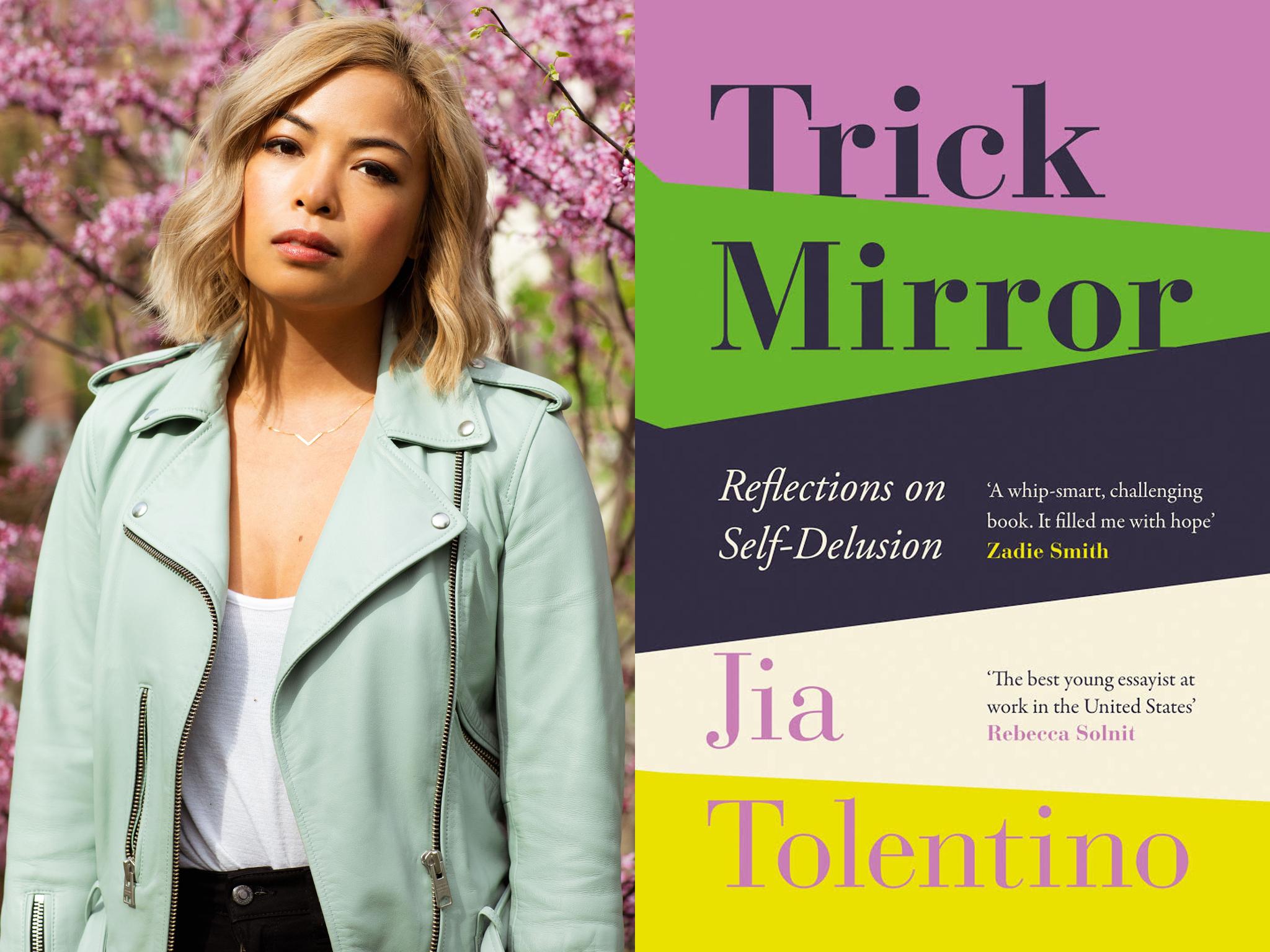

Trick Mirror by Jia Tolentino, review: A profound survival guide for an increasingly isolating world

Jia Tolentino’s collection of essays speaks like no other to the millennial condition, writes Adam White

Jia Tolentino has spent the past decade as our foremost expert on how to exist in the 21st century. Her work, as a staff writer for The New Yorker, often doubles as a kind of existential survival guide, regularly driven by how odd it is for a generation to have to navigate a world increasingly lived online, where toxicity, capitalist horror and self-loathing has long bled into our everyday existences.

In her best work, she uses the rise of the internet to chart our collective anxieties. During Trick Mirror, her first collection of essays, she writes about her earliest memories of the digital world, the Angelfire web page she filled with choppy HTML flourishes and Dawson’s Creek references. She then explores how it all became corrupted, the endless possibilities of the internet growing harsher and meaner, until it felt like we had become at the mercy of an online world that had shaped our real-world personalities for the worse. “Where we had once been free to be ourselves online,” she writes, “we were now chained to ourselves online.”

Those deep dives into internet culture provide the collection with many of its most profound moments. Morphing mere trivia into quietly devastating blows, she talks of how the architecture of the internet has led to its worst impulses. That the default username for 4Chan members is “Anonymous” could only have given way to trolling and hatred, she reckons. And that we shouldn’t be surprised by how important identity has become on the internet when so much of the foundations of social media revolves around profile pages and self-written biographies.

She also guiltily uses her own history in journalism to explore how things went so awry, particularly positive-seeming movements that unknowingly left far more insidious problems in their wake. The anti-Photoshop crusades that propelled to notoriety the late-Noughties feminist site Jezebel, Tolentino’s one-time home, unknowingly spawned an expectation that women should strive for a “natural” beauty which “requires almost no intervention”. In another essay, she reflects on the rise of think pieces that celebrate “difficult women”, stories that have reframed the likes of Kim Kardashian, Lena Dunham or Caitlyn Jenner as feminist icons importantly disrupting the status quo. Not that they shouldn’t be idolised, she argues, but that it’s had an unexpected trickle-down effect wherein more politically dangerous individuals like Ivanka Trump have undergone similar reframing by mere proxy of being a woman in power. “Feminists have worked so hard, with such good intentions, to justify female difficulty that the concept has ballooned to something all-encompassing,” Tolentino writes. “A blanket defence, an automatic celebration, a tarp of self-delusion that can cover up any sin.”

Many of the essays in Trick Mirror end up diverging in wildly different directions. Reality TV Me begins as a nostalgic road trip into Tolentino’s appearance on a forgotten reality series in her teens, before becoming a stirring exploration of mental illness, adolescence and presentation of self. Always Be Optimising, arguably the strongest essay here, is outwardly about the cult of athleisure wear, its odd relationship with class and its hypersexual undercurrent (“Athleisure can be viewed as a sort of late-capitalist fetishwear,” she writes). But it also delicately unfurls as it goes, roping in discussion of female beauty, the psychology of the chopped salad, Tolentino’s time in the Peace Corps and the history of the Barre Method.

It’s in these moments where Tolentino’s background is most apparent – in her work, she represents the language of the internet, its dizzying distractions and its abundance of information, thoughts spiralling into other thoughts. And it’s only through her authorial control that Trick Mirror is all so endlessly captivating, themes gliding into one another rather than messily piling up. It’s a risky format that doesn’t always work – an essay in which she tracks her own life through the literary heroines she grew up with never truly coalesces – but is always nonetheless rewarding. Only some, as is the case with any collection of essays, are more rewarding than others.

At the end of each of her essays here, Tolentino struggles to discern any real answers. In some cases, she’s almost fatalistic, acknowledging the likelihood of social and economic collapse, or the pointlessness of speculating about things that are, whether we acknowledge them or not, here already. But there is something deeply comforting about the fact that for every ponderous and neurotic question we ask ourselves about the internet or capitalism or how to live and breathe in 2019, somewhere out there is Tolentino, if far more eloquent and thoughtful than we could ever be, asking them too.

‘Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion’ by Jia Tolentino is published by 4th Estate, £14.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks