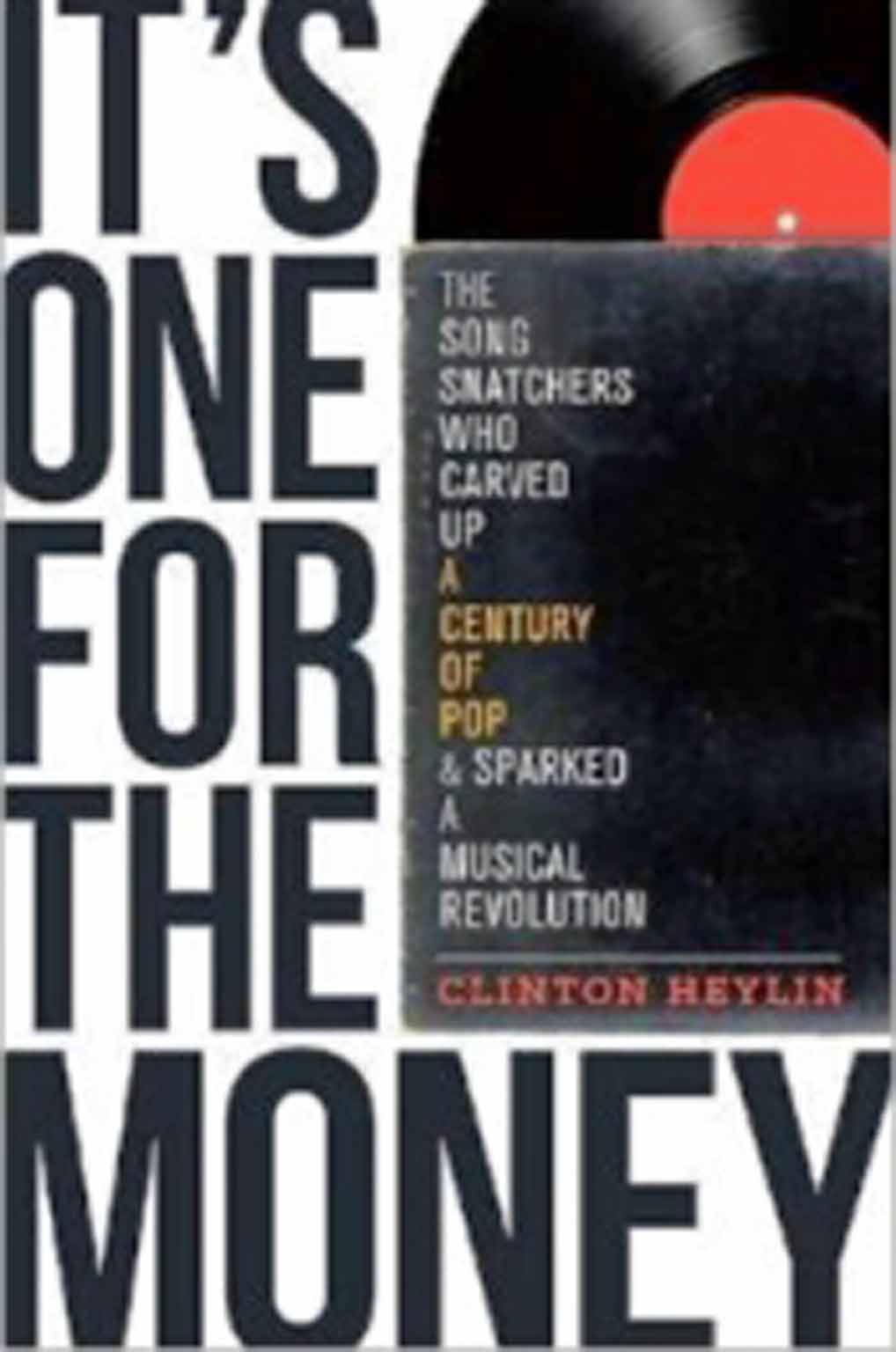

It's One for the Money: The Song Snatchers Who Carved Up a Century of Pop & Sparked a Musical Revolution by Clinton Heylin - book review

An eye-popping look at rock's robbers has got it covered

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.We've all heard of the higher-profile musical plagiarism cases – "My Sweet Lord" and its "unconscious" appropriation of the Chiffons' "He's So Fine" is probably the best-known example. But George Harrison is only one member of popular music's light-fingered legions. Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan, Jimmy Page, John Lennon, Paul Simon – the larcenous list is truly extensive.

Since the very beginning of the story of pop and rock, when the music of black America was being refined and packaged, written down and recorded for the first time, thievery was more than a mere blight on the creative and business process: it was central to how the system operated. Vast numbers of traditional songs were snatched up in a mad land-grab that continued until the likes of Dylan and Page a few decades ago.

WC Handy, the so-called "father of the blues", set the template with his wildly cavalier approach to ownership and publishing rights: Jelly Roll Morton, for one, was incensed. Of the tunes Handy claimed as his own, he wrote: "I had heard them when I was knee-high to a duck." To which Handy gave an honest and revealing answer: "If he is as good as he says he is, he should have copyrighted and published his music."

That approach has served many well down the years, like the Animals' keyboard player who attached a "Traditional arr. Alan Price" credit to "House of the Rising Sun", and Paul Simon, who was taught "Scarborough Fair" by Martin Carthy and pulled off the same trick. Then there have been the more blatant steals, Led Zeppelin's Page being perhaps rock music's most shameless robber baron.

The book is fabulously well researched, unearthing such curios as Glen Matlock's debt to ABBA. The Sex Pistols' first bassist based his killer riff for the band's third single, "Pretty Vacant", on the Swedish popmeisters' "SOS", he confesses, delivering what in some ways is the book's key line: "That's what songwriting is all about. Everything's nicked from something else."

Heylin talks to ex-band members who made crucial but unrewarded contributions, like Bill Wyman, who claims to have come up with the riff for "Jumping Jack Flash". Then there are the copyright kings, like Mick Jagger who know that if they change a single line, a song becomes half theirs.

It's a story well told, in eye-popping detail, and it doesn't need perking up with Heylin's relentlessly waggish tone. For all its myriad delights, popular music, one can only conclude, is a deeply grubby business.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments