I Met Lucky People: The Story of the Romani Gypsies by Yaron Matras, book review

The Romani face a lot of prejudice about their way of life, but is it so different from our own?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

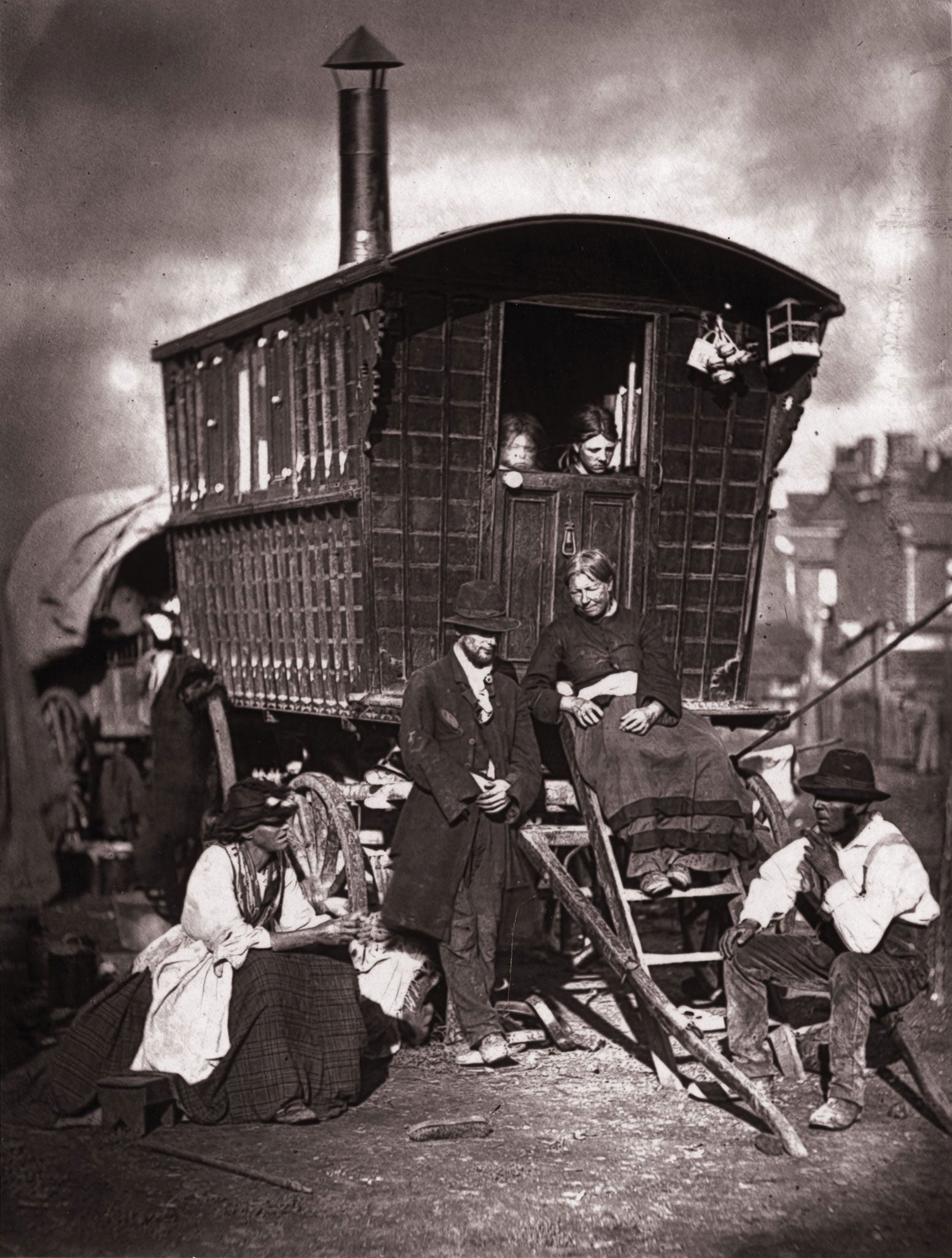

Your support makes all the difference.Who are the romani people? They are, Yaron Matras writes, a nation like no other, without territory, sovereignty or institutions, and with no tradition of agriculture or ownership of land. Yet they are also a model of cultural tolerance and flexibility who “are the only nation in Europe and western Asia that has never declared war on another nation and that has never tried to subjugate others into adopting its ways”. We have a lot to learn from them.

Romani history is unseen and unrecognised. Matras synthesises what facts we have to create a visible, compelling record. I Met Lucky People explores Romani society, customs, language, identity – and history. Their history possesses a merciless quality. “I travelled long roads and I met lucky people” is the first line of the song “Gelem, Gelem”, now the Romani national anthem written by a survivor of three concentration camps during World War Two.

The genocide of the Roms under the Nazis is usually invisible – because of the Romani fear of the dead, and the shame of the brutalised survivors. Humiliation continued after the war. Although investigations took place, no criminal charges were brought against any of those suspected of the genocide of Gypsies.

Yet knowing more about the Roma is “not a guarantee for tolerance, nor is it a prerequisite for affection” – although the Roma have found friends in the European Parliament, The World Bank and the Open Society Institute.

Knowledge of their culture can find itself at odds with the double-bind of Gypsy romanticisation. The exotic image of Gypsies – apparent superpowers, ability to tell fortunes – has not only been foisted upon the Roma but sometimes self-cultivated to maintain invisibility within a hostile and, at times, lethal majority culture. Matras has little time for the exotic, nor for the fiction and fantasy that “have dominated the depiction of Gypsies in the arts and literatures for many centuries”. Academic study, he claims, is the best answer to prejudice. I’d argue that the imaginations of Romani artists such as Delaine Le Bas, and dramatists such as Dan Allum of the Romani Theatre Company, are equally essential to addressing that challenge.

Matras detects small, significant enlightenments both within the Roma community and in Gadje (non-Roma) cultures. Some of these are local events with larger implications. Since 2010, for example, Manchester Roma immigrants worked successfully with schools, police, academics and charities. Their ‘Roma Strategy’ project is an example that dealt with realities, not Gadje bigotry or Roma self-romancing. School attendance of Romani children outstripped that of non-Romani children.

Matras raises fascinating questions. Can one become Romani by adoption or choice? Are we all Gypsies? He believes that “in embracing global, transnational and cosmopolitan attitudes, we are becoming in some ways more like the Roms, while the Roms are adopting some of our ways”. Romani identity has assumed “a new twist”. It is rarely a matter of heredity (the Nazi death-camps having obliterated thousands of family lines), but of the narratives we shape and share. Matras believes that negotiating a Romani identity is now as much about being free to pick who we are, and what blend of customs and values we call our own. As citizens of the world, there is fresh force in the Angloromani phrase: “We are all one: all who are with us are ourselves”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments