I Call Myself a Feminist and Letter to a Young Generation: 'From zinging truth to giddy faith' - book reviews

'Fourth-wave feminism has galvanised an internet-savvy, internationally-interacting, next-generation of young women'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

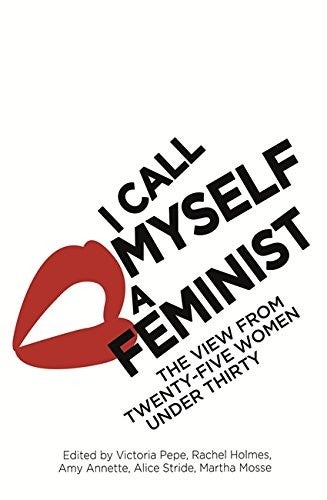

Your support makes all the difference.In 2013, Fifty Shades of Feminism provided a platform for a multitude of feminist voices. I Call Myself a Feminist halves the number – and slashes the age range, to offer “the view from twenty-five women under thirty” (alongside lots of inspirational quotes from feminists from Mary Wollstonecraft to Tina Fey). It’s a sound endeavour: fourth-wave feminism has galvanised an internet-savvy, internationally-interacting, next-generation of young women. That they deserve a platform is irrefutable.

This book, however, is a decidedly mixed bag. The term intersectionality is flashed like a membership pass so often, it’s no surprise to find a careful diversity of backgrounds here. There are (at least) three writers who can put Cambridge University in their biog, and familiar surnames – Emily Benn, Laura Pankhurst, Martha Mosse – but the collection also features a Danish stand-up comic, a Turkish former asylum seeker, and a Canadian academic, plus several writers whose work explicitly tackles race as well as gender.

There are many chapters here that enlighten, cheer, or rightly anger. Some have real style and swagger – see Sofie Hagen, Caroline Kent, or Amy Annette – but the best are often those that refract wider social questions through the prism of personal experience. Actress Jade Anouka’s role in an all-female Shakespeare production, Naomi Mitchison’s perspective on being a woman and an engineer, and solicitor Rosie Brighouse’s passionate defence of the Human Rights Act all zing thanks to their truthfulness and specificity. Abigail Matson-Phippard’s essay on consent is also superb, calmly tackling a subject on which contemporary feminism can be shrilly dogmatic, with grace, nuance, and wisdom.

But there’s an overall uncertainty of who the intended audience is, and the tone can be wobbly. Some essays strive for high-mindedness, with po-faced mini-lectures on the basics of intersectionality or gender non-conformity, as if you have to prove you can use the term “cis-male” correctly before being allowed an opinion. The other pull is towards a snappy, unabashedly youthful voice, replicating the total overshare and CAPITALS FOR EMPHASIS of a whip-smart blog post.

In their introduction, the editors swerve between suggesting that feminism is exhausting and hip. The very term “feminist” is “too inclusive and broad”, and yet still rejected by many “who refuse to identify with it”. These contradictions are real, but not effectively unpacked here. And in arguing that the book must be “all-inclusive”, they compare this to “the crap holiday you went on when you were 18 … from which you came back with [a] new-found talent for ‘tactical vomiting’” – an effortful attempt to bring the lolz, that potentially turns off the sort of diverse groups they profess to attract ….

If you’re even vaguely engaged with contemporary debates around feminism, a lot of this book will read as wearyingly simplistic – a broad-sweep at over-exposed targets. However – and at the risk of sounding patronising myself – I would thrust it at any young teenagers dipping first toes into the feminist water. Helene Cixous it may not be (thank Christ), but I Call Myself a Feminist provides a lively and heartfelt introduction to many of the flash points of feminism, and manages to be both relatable and inspirational.

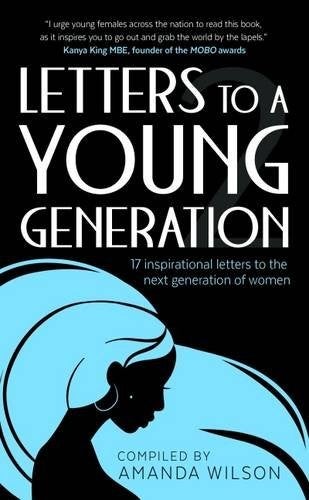

I’d be hard-pressed to recommend Letters to a Young Generation to anyone. This slim book of letters from successful black British women to imagined young black female readers is stuffed with vapid self-help clichés: “Be in control of your own destiny!” “Go rock the world in your heels!” “YOU ARE BEAUTIFUL, AMAZING & WONDERFUL … RIGHT HERE, RIGHT NOW!!!”

It deals in platitudes and dream-peddling for a generation who’ve already been raised on The X-Factor, The Apprentice and motivational memes on Facebook. Despite the gendered focus, feminism isn’t mentioned, and racism usually only as a personal obstacle to overcome; there’s no wider discussion of changing society, consciousness raising, or structural reasons for struggle. Letters to a Young Generation is single-minded and brutally individualistic: almost every contribution is about achieving your dream job, being successful, even ditching friends that hold you back.

Such aspirations may be partly due to a contributor list heavily skewed towards business and entrepreneurship, alongside the odd celeb such as Ms Dynamite and Sinitta. Yes, many teenage girls do need a great big injection of self-esteem, and there are many flashes of sound advice in here, but the overall tone is one of giddy blind-faith in everyone being special and magical and able to achieve anything they put their mind to.

It’s a message that the book’s copy-editors might have taken more notice of – this may be full of work-hard and aim-high rhetoric, but there's plenty of rogue punctuation. My advice to a younger generation? It’s never OK to use three exclamations marks.

I Call Myself a Feminist, Edited by Victoria Pepe, Rachel Holmes, Amy Annette, Alica Stride and Martha Mosse, Virago, £13.99

Letter to a Young Generation, Compiled by Amanda Wilson, 9:10 Publishing, £6.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments