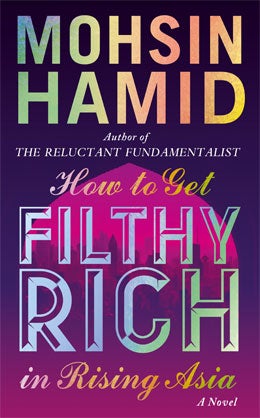

How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia, By Mohsin Hamid

A DIY guide for a budding slumdog millionaire

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mohsin Hamid’s third novel is a classic rags-to-riches story told in experimental form.

An Asian boy hailing from the harsh terrain of village life pulls himself up by his bootstraps to become a hotshot water industrialist in the city. Embedded within this tale of smooth self-invention is a not-so-smooth love story: a pretty girl and sometime lover is just out of his reach and the desire to win her over is partly what motivates his upward climb. To this end, she could be Daisy to his Jay Gatsby: the yearning for wealth and position is caught up in a yearning for her.

If the story is slightly overfamiliar, the way it is told is most certainly not. Like Hamid’s previous novels, this too is narratively unconventional. Written as a self-help book, he addresses his protagonist as ‘you’. The ‘you’ is not named. Neither is the country or city he lives in nor his wife or son, who are all referred to in generic terms – his lover is always “the pretty girl” no matter how old she grows.

It is this daringly original narrative conceit that simultaneously launches us into the drama and distances us emotionally from its characters. The langauge is lean, witty, and begins by hitting just the right note of breezy pastiche. Gradually the self-help concept begins to jar, and the omniscient tone sounds increasingly grating. Hamid persists is reminding us of the fact that this is a self-help book and that he is its tongue-in-cheek writer in almost every chapter, lest we forget. “As my writer’s fingers key and your readers eyes flick, you [the character] stand at the cusp of the eighth decade of your life...”

Paradoxically, though its form seems designed to distance us from characters’ inner lives, it still manages to draw us in at times. The death of the main character’s mother from cancer – protracted because treatment is unaffordable – is quietly devastating. So is the everyday tragedy of ageing that the book captures so well. Its many ellipses mean lives jump ahead, sometimes by decades, and we find out that the main character has now married, now had a son, and got struck down by illness, so drawing our eye to both the sudden turns and predictable events that occur in a lifespan.

Wealth – its accumulation and its loss – clearly preoccupies Hamid. Past protagonists have been men who initially embody the middle-class dream to work hard, to become somebody of consequence, before this ambition is interrogated and derailed. Hamid’s debut, Moth Smoke, was a story of a banker in Lahore who lost his job and faced a sharp decline in fortunes. His second celebrated novel, The Reluctant Fundamentalist, which has just been beautifully adapted for film by Mira Nair, featured a thrusting young man who chased after America’s ‘corporate world’ dream until he was stopped in his tracks by 11th September.

How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia breaks away from this pattern of ‘stalled’ ambitions. This boy from the village succeeds in what he sets out to do. He makes it big, turning himself from a penniless nobody into an affluent somebody, though the narrator suggests this comes with its own moral compromise.

As page-turning as Hamid’s book is, in the end its effect is remarkably similar to that of a self-help book – glib in tone, forgotten soon after it is put down.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments