How the Blitz shaped Britain's future: A new country arose from destruction caused by the aerial assault launched 75 years ago

Seventy-five years ago this week, the Blitz began: eight months of terror that tested Britain to the limits. But as Joshua Levine reveals, on this broken ground the first faltering steps were taken towards building a better country

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ida Rodway was an ordinary, law-abiding woman in her late sixties from east London. In early October 1940, she went to fetch her blind husband, Joseph, his morning cup of tea. But as the water boiled, Ida changed her mind. She picked up an axe and a carving knife instead. Returning to her husband, she attacked him with the axe.

Ida was a devoted wife. Joseph's brother never remembered the couple sharing a harsh word. But they were as much victims of the Blitz as anybody killed by an aerial mine or a high explosive bomb. In September, they had been bombed out of their Hackney home and, after several days in hospital, had begun sleeping on Ida's sister's floor. Joseph's mental state was deteriorating and he rarely knew where he was. They were about to lose their labour money and Ida had no idea how or where they were going to live, or what to do about the bombed house that still contained all their possessions.

Hopeless, helpless and overwhelmed, she did what she considered to be the kindest thing for her husband. Charged with murder, she was found unfit to plead at the Old Bailey, and committed to Broadmoor, where she died a few years later.

Ida Rodway's story offers a dark window onto the Blitz, a period as shocking to the authorities as it was to the ordinary people who found themselves on the front line. As the bombing began, the government was unable to cope with the chaos and misery caused. It had anticipated hundreds of thousands of deaths – but this nightmare had not materialised. Instead, it was faced with large numbers of homeless people with nowhere to stay, no money, clothes or possessions, and no idea about what to do about any of these things. In their suffering, the Rodways were not alone.

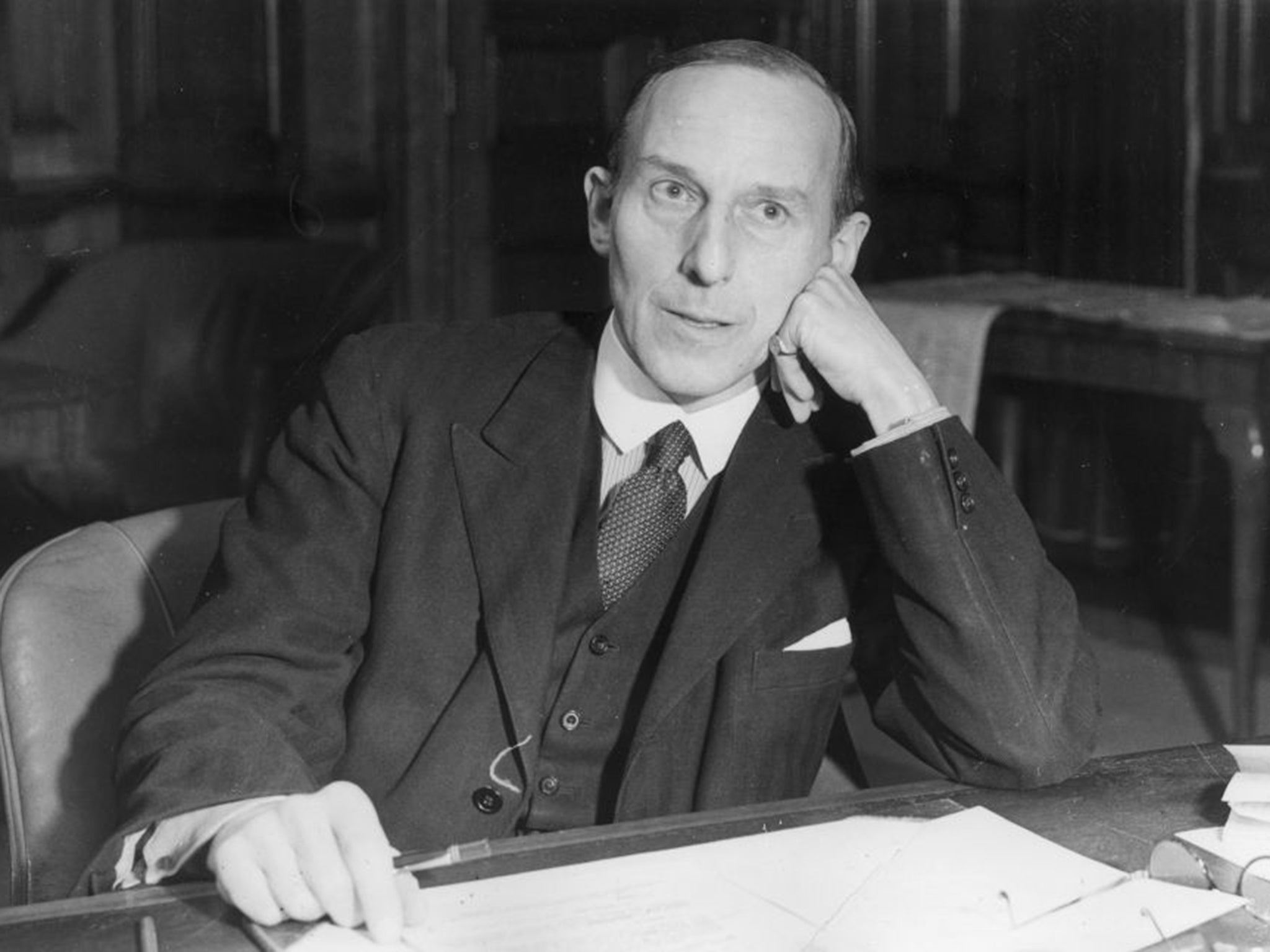

The government's reaction in October was to appoint a long-forgotten hero named Henry Willink – a Conservative Member of Parliament – to overhaul the structure of London along progressive lines. Willink, a Great War artillery officer who understood the concept of a front line, started to make replacement housing available. He organised large-scale repairs. He removed the "poor law" stigma that was making claimants feel more like Dickensian beggars than victims of strategic bombing. He introduced benefits and information centres where the dispossessed could receive assistance in a single, well-publicised location.

With the help of swiftly trained social workers, these measures were effectively introduced and, while they came too late to help Ida and Joseph Rodway, they transformed the experience of countless others and brought an end to London's crisis.

These reforms can be seen as the early stirrings of the welfare state, an acknowledgment that the vulnerable were to be protected rather than judged. With suffering now shared among the population, a sense of collective responsibility began to emerge. And while the Blitz was certainly a time of terror and misery (nearly 100,000 were killed or seriously injured by enemy action over eight-and-a-half months of enemy action) the rarely acknowledged fact is that modern Britain owes a great debt to the period. Much that we take for granted today emerged like the phoenix from the flames.

The Blitz, after all, changed the attitudes and expectations of the nation's citizens. Lives were lived in the shadow of death and invasion. People did not know how or whether they would cope, and they surprised themselves with their actions. They pulled together and helped strangers. They spoke to each other for the first time. They found common ground amidst the chaos where none had existed before.

Joan Varley was a young woman who spent her evenings studying at the London School of Economics. One night she boarded a bus, climbed to the top deck and sat at the back. There was only one other person up there, a man sitting at the front. As the bus drove through Westminster, Joan heard a bomb falling. Evidently, the bus driver heard it, too: he made a sharp right turn. He weaved through unscheduled streets, and the bomb exploded elsewhere. But as it descended, the man at the front had walked down the bus, sat next to Joan and taken her hand. "Neither of us spoke a word," she remembers, "and once we were through the bomb area, he moved back to the front seat without a word being said."

Blitz Spirit, it is clear, was no myth – and Joan Varley experienced it in a pure, distilled form. But just as the Blitz brought people together, so it caused them to break rules and to exploit each other. And sometimes it did them all at the same time.

Wally Thompson was a career criminal who described the Blitz as a golden time for lawbreakers. Thompson became an air raid warden – mainly in order to wear the uniform. (As an ARP man, he could move around London carrying large items without suspicion.) One night, during a heavy raid, he parked a stolen van outside a warehouse in London Bridge. With him was his gang of three accomplices – Batesey, Bob and "Spider" – and together, they planned to steal a safe from the office. At the appointed time, they broke in, and began manhandling the safe through the front door – when a bomb fell nearby. "The ground heaved towards us like an uppercut," remembers Thompson.

Choked and blinded by dust, the burglars were thrown into the air, but all were unharmed, and three of them began to run.

Spider, however, had other ideas.

A cat burglar by trade, he was adept at scaling walls. Spotting a young girl trapped in an upper window, he struggled up the wall to reach her. By the time he had her in his arms, a fire engine had arrived to bring them both down safely. A policeman was so impressed by Spider's courage that he asked him for his name and address. He wanted to recommend him for an award. Spider declined and left the scene quickly. The last thing he needed was public recognition.

This story is a useful metaphor for the strangeness of the Blitz: in the flash of a bomb, a criminal gang went from stealing a safe to saving a life. Many ordinary, law-abiding citizens were turned into outlaws by the myriad new regulations that made everyday activities (turning on lights, driving a light-blue car, making profits) into punishable crimes. And even when danger was not immediately present, the nation's temperature was raised by the period's steady brutality.

Take the case of George Hobbs, a 43-year-old mortuary assistant found guilty of stealing items from the bodies of air raid victims. The sentencing judge described these actions as "horrible and disgusting", and while it is difficult to disagree, Hobbs's plea in mitigation is revealing. Nobody, he protested, could possibly imagine the sight of bodies recovered from bombed premises. Combined with the ever-present dread that the same would happen to him, Hobbs said his mind and behaviour had been turned. It is customary in the legal profession to treat pleas in mitigation with scepticism – but here was a first-time offender whose world had twisted out of all recognition. Blitz Spirit is often (rightly) celebrated. Actions such as Hobbs's are rarely admitted. Yet they stand together as twin symptoms with a common cause.

And as the Blitz was pushing citizens towards extreme behaviour, it was having the same effect on the country itself. Great Britain, constant in her traditions and practices, was forced to take risks and find new ways of existing. It is barely remembered nowadays, but Sherwood Forest was turned into the hub of an inshore oil industry that provided British aircraft with the high-grade crude they needed to resist the Luftwaffe. To the amazement of experts, the oil proved to be of higher quality than Iranian crude, but Britain lacked the equipment and men to drill for it effectively. And so a band of rough-and-ready drillers from Oklahoma and Texas was shipped across the Atlantic to tackle the problem.

This story demonstrates more than just international co-operation. It represents an extraordinary shift in the nation's conduct and expectations. The oilfield would never have been attempted at any other time. This was a period of misrule when strange rituals were adopted. People may have been taking risks and behaving unexpectedly, but the same was true of the country – of the land – itself.

It would be a mistake, however, to think of the Blitz as a brutal anomaly in Britain's story; a time apart from ordinary life. The oilfields persisted into the 1960s and were only finally made redundant by the discovery of North Sea gas and oil. The Blitz's social and political changes continue to influence us today. And though it is customary to compare modern Britain unfavourably with the stoic, uncomplaining nation of the war years, there are surprising parallels to be found.

In 1940, Cecil Hughes, an electrician in Oxford, arrived at the home of a Mrs Bates in Divinity Road. As he worked, he suggested that Ribbentrop would be made king when the Nazis arrived and remarked that the country would probably be as well off under the Germans. Considering this "a queer way for a British subject to talk", Mrs Bates telephoned the police, and Hughes duly found himself charged with the new crime of making a statement likely to cause alarm or despondency.

In 2010, Paul Chambers, a 28-year-old accountant, posted a message on Twitter expressing his desire to blow up Nottingham Airport after his flight was cancelled. He, too, was charged with a newly created offence: sending a menacing message.

The fact is that both Hughes and Chambers were joking. Hughes's conversational style may not have appealed to Mrs Bates, but as he told magistrates at Oxford Police Court, his words were meant to be "jocular" and that he had "light-heartedly" been suggesting that things in Britain "were not up to scratch". Seventy years on, Chambers' tweet was also a joke. The staff at the airport designated it a non-credible threat, which might almost be the technical definition of a joke. It was a bad joke, sure, but not very different from countless other weak stabs at humour posted daily on social media. Yet both Hughes and Chambers were found guilty.

Another parallel between the Blitz and the present day was ignored by Prime Minister David Cameron in the wake of the 2011 summer riots. Speaking in the House of Commons, Mr Cameron said: "The truth is that the police have been facing a new and unique challenge with different people doing the same thing – basically looting – in different places all at the same time."

In fact, this challenge was neither new nor unique. Looting was widespread throughout the Blitz. Seventy-one years later, Mr Cameron blamed the latest outbreak on a lack of discipline in schools, the modern absence of morals, and an over-generous benefits system. Yet it had taken place before the creation of the welfare state, at a time when caning was common in schools and the courts were ordering the birching of juveniles and flogging of adults.

The simple fact, shorn of political hot air, was that looting was a reaction to opportunity. In 1940 and 1941, people acted on the spur of the moment in extraordinary circumstances. The same was true in 2011. Seventy-five years after the start of the Blitz, as living memory gives way to neat historians' theories, the time has come to acknowledge the nuanced reality of a formative period for Britain in which danger, misery and the breaking down of certainties caused people to behave both well and badly; to interact meaningfully; to see the world from other viewpoints. And as expectations changed, so the fight against Nazism became entwined with the fight for a better future.

This reaction can be seen in the response to Coventry's destruction by the Luftwaffe in November 1940. Within weeks, the city's misery was being viewed as an opportunity for progress. A contemporary BBC radio programme recorded the hopes of local people. They wanted clean, modern houses with indoor toilets, built-in cupboards and gardens. They wanted decent schools, shopping centres and opportunities for adult education. But above all, they wanted an indication that society cared about them.

Henry Willink's re-ordering of London can be seen as the first signal, in the midst of war, that the future might be different from the past. As the months passed, other progressive seeds were sown. In February 1941, the Ministry of Health began drawing up plans for a post-war National Health Service. Shortly afterwards, the President of the Board of Education, Rab Butler, laid the groundwork for his education reforms, which would make free secondary schooling available to all.

At the heart of these shifts in thinking were the horror and shared values of the Blitz.

This was not a time for ideology or party politics, but one when necessity and pragmatism guided the country. Henry Willink and Rab Butler were both Conservative politicians – as were most members of the Cabinet War Aims Committee which, in 1940, advocated an end to a society based on privilege. In future, argued these old Tories, a reasonable standard of life would have to be secured for the whole population.

Ordinary men and women built armaments, they served in the forces and they bore the bombing patiently. The Blitz may have been a time of misery for many, but it was also a time when the sacrifices made by British people began to tilt the balance of society in their favour. Compensations would be offered, and the People's War would become the People's Peace. Yet today, many of the measures and institutions that arose out of the Blitz appear under threat. It will be very sad if the true legacies of Blitz Spirit are allowed to erode – because we fail to remember how hard they were won.

The Secret History of the Blitz by Joshua Levine (Simon &Schuster, £16.99) is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments