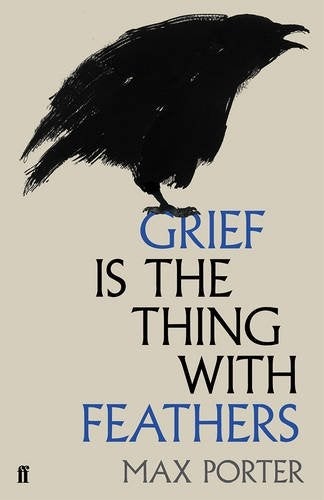

Grief is the Thing with Feathers, by Max Porter - book review: In Hughes’ shadow

Faber & Faber - £10

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Some writers would content themselves with one linguistic form for a debut novel. But perhaps as a consequence of his day job as senior editor for Granta, Max Porter couldn’t restrict himself to a straightforward narrative. Instead, he chose none at all. Grief Is The Thing With Feathers is billed as “part novella, part polyphonic fable, part essay on grief”. It is a cacophonous snapshot of the trauma felt by a family after the sudden death of their mother, told alternately by “Dad”, the “Boys” – and “Crow”. Porter’s conceit is to turn the emotion of grief into a black bird, who swoops into the bereaved family’s life in “a rich smell of decay, a sweet furry stink of just-beyond-edible food, and moss, and leather, and yeast”.

This deluge of sensation is typical of Porter’s description throughout the book, particularly in Crow’s sections. It is sometimes a slog to trawl through paragraphs in which Porter appears to have been unable to cut a single superfluous adjective. And having to break off continually to Google Ted Hughes doesn’t help. For the “crow as grief” conceit is not Porter’s invention. After Sylvia Plath’s suicide, Hughes stopped writing. Crow: From The Life and Songs of Crow, a collection of poetry composed 1966-69, was his means of working through his grief. Unfortunately Porter relies a little too much on the reader’s knowledge of this. “Fourteen months to finish the book for Parenthesis Press; Ted Hughes’ Crow on the Couch: A Wild Analysis ... Parenthesis hope my book might appeal to everyone sick of Ted & Sylvia archaeology,” writes Dad. Suddenly, every abstract turn of phrase that had before simply alienated seems decipherable – given a good working knowledge of mid-20th century modernist/post-modernist poetry.

Then there’s that title. Those unversed in modernist poetry might presume it a line from Hughes’s Crow. In fact, it is a riff on a poem by Emily Dickinson, “Hope” is the thing with feathers. In Dickinson’s poem, hope in the form of a bird is omnipresent and self-sustaining. Porter’s appropriation of the metaphor darkens Dickinson’s positive little poem. Grief, once suffered, will never leave entirely – but it can gradually morph into something more bearable. It is just a pity that the guiding metaphor “Crow” is so obviously used to make this point: at worse an annoying distraction from an otherwise touchingly simple expression of human grief.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments