Dylan Goes Electric! by Elijah Wald, book review: The times really were a-changin'

An absorbing account of the moment when the voice of a generation irked the folk scene and plugged in his guitar

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

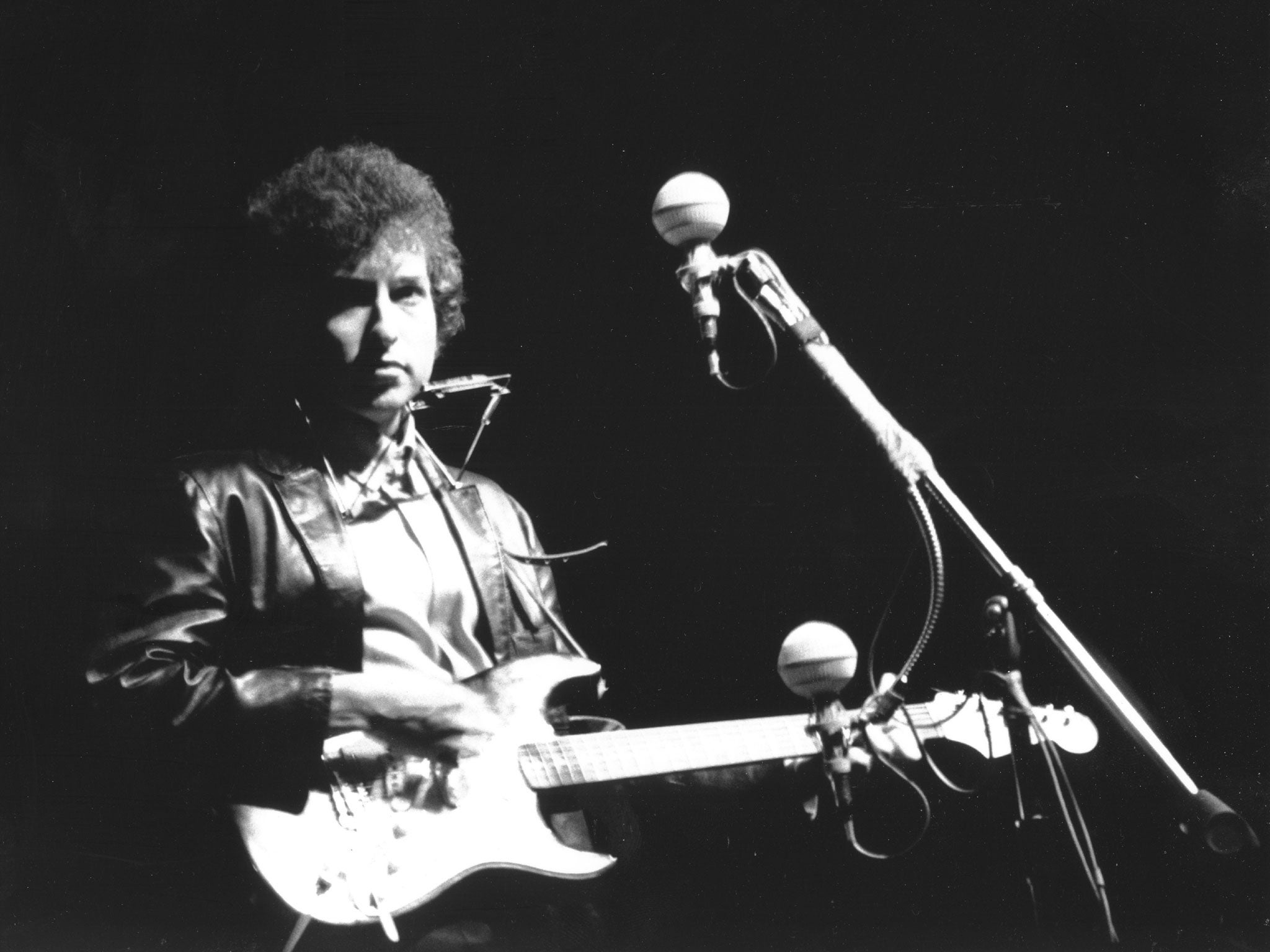

Your support makes all the difference.These days, it's rare for a performance by a single artist to have such cultural resonance that it becomes emblematic of an era. One thinks of Elvis, and then the Beatles, on The Ed Sullivan Show. But Bob Dylan's epochal appearance at the 1965 Newport Folk festival backed by an electric blues band is of a different order, thanks partly to the antipathy it roused. It lasted just three songs, but became one of the moments around which music history pivots.

As the legend has it, an outraged old guard personified by folk's elder statesman Pete Seeger strove to stop the show – Seeger supposedly attempting to chop through the power cables with an axe – while fans erupted in a conflicted cacophony of boos, cheers and protests against the sheer volume of the performance, as much as what it signified. But it was not simply that Dylan had transgressed the festival's acoustic bias: the intemperate reception was in part a protest that the folk scene's unrivalled laureate had turned his back on the "duty" to protest, in a style of singalong simplicity, in favour of more personal themes, tackled in a more personal language. It was a moment of fracture between artistic modes: as Elijah Wald notes in this absorbing, detailed overview of the event, "the instrumentation connected [Dylan] to Elvis and the Beatles, but the booing connected him to Stravinsky".

Wald sets this brief, climactic moment in the context of the folk scene in general, going back to its roots in the hootenanny spirit of the Forties and Fifties, when first the Almanac Singers and then the Weavers (both featuring Seeger) developed the topical-song style into a commercially viable strain, which the Kingston Trio would take to the top of the charts.

But the folk scene of the Fifties and Sixties was as notoriously riven by internecine disputes as the Judean liberation struggle in Life of Brian, with traditionalists, purists, topicalists, modernists and collectivists engaged in a constant battle for the soul of the movement, and any kind of success was inevitably condemned by purists as a dilution of the music's authenticity, and denigrated as "folkum" and "fakelore".

It was a battle which Seeger was uniquely placed to referee, and during the early years of the Newport Folk Festival, he sustained a fractious truce between the various interests. But when he, like the folk world en masse, embraced the young Dylan as the reborn spirit of Woody Guthrie, he unwittingly took a viper to his bosom, in the person of Dylan's manager Albert Grossman, "the snake in the folk scene garden", whose business acumen and shrewd manoeuvring helped build the singer's reputation (even Dylan's old crony Bob Neuwirth concedes that Grossman "invented" Dylan). But equally important was Grossman's coup in horse-trading the popularity of his other act, Peter, Paul & Mary, to secure Dylan a headlining slot at the 1963 festival, which effectively cemented his charge's position as the folk scene's inspirational auteur.

By the following year's festival, Dylan was being introduced on stage with the presumptuous claim, "You know him, he's yours!". But he was no such thing. Even as his protest anthems washed torrentially over youth culture, the singer himself had swiftly wearied of being the left's pet protest poet. Shortly before the release of The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan in 1963, he observed in an interview with Studs Terkel that the present situation lacked the certainties that spurred Woody Guthrie, that "there's more than two sides, y'know? It's not black and white anymore".

And it had only grown greyer by the 1965 festival, as confirmed by the Rashômon-like recollections of the occasion, depending on which position the observers held.

Wald examines the entire three-day festival in forensic detail, placing the headline historical event in a thorough context, which shows more clearly the burgeoning divide between the old guard's weakening hold, as the more traditional acts played to diminishing crowds, and the immense power wielded by Dylan, whose new fans overwhelmed the occasion.

What's not in doubt is that Dylan's set was not the weekend's first "electric" performance – the Paul Butterfield Blues Band (from which came the bulk of Dylan's backing band) played the day before Dylan (prompting a fist-fight between folk archivist Alan Lomax and their manager Grossman, an amusingly symbolic struggle between conservator and commercialiser). Nor was it a surprising shift, artistically: he had already released his first "electric" album, Bringing It All Back Home, and the current "Like a Rolling Stone" was his third rock single of that year. But symbolically, it was momentous, a line in the sand drawn between the past and the future, collectivism and individualism, naturalism and abstraction, simplicity and complexity. And, some felt, between hope and nihilism.

History, however, can be a capricious mistress. That same weekend, president Lyndon B Johnson committed the US to a ground war in Vietnam, a truly momentous event overlooked by all but one of the performers at the festival.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments