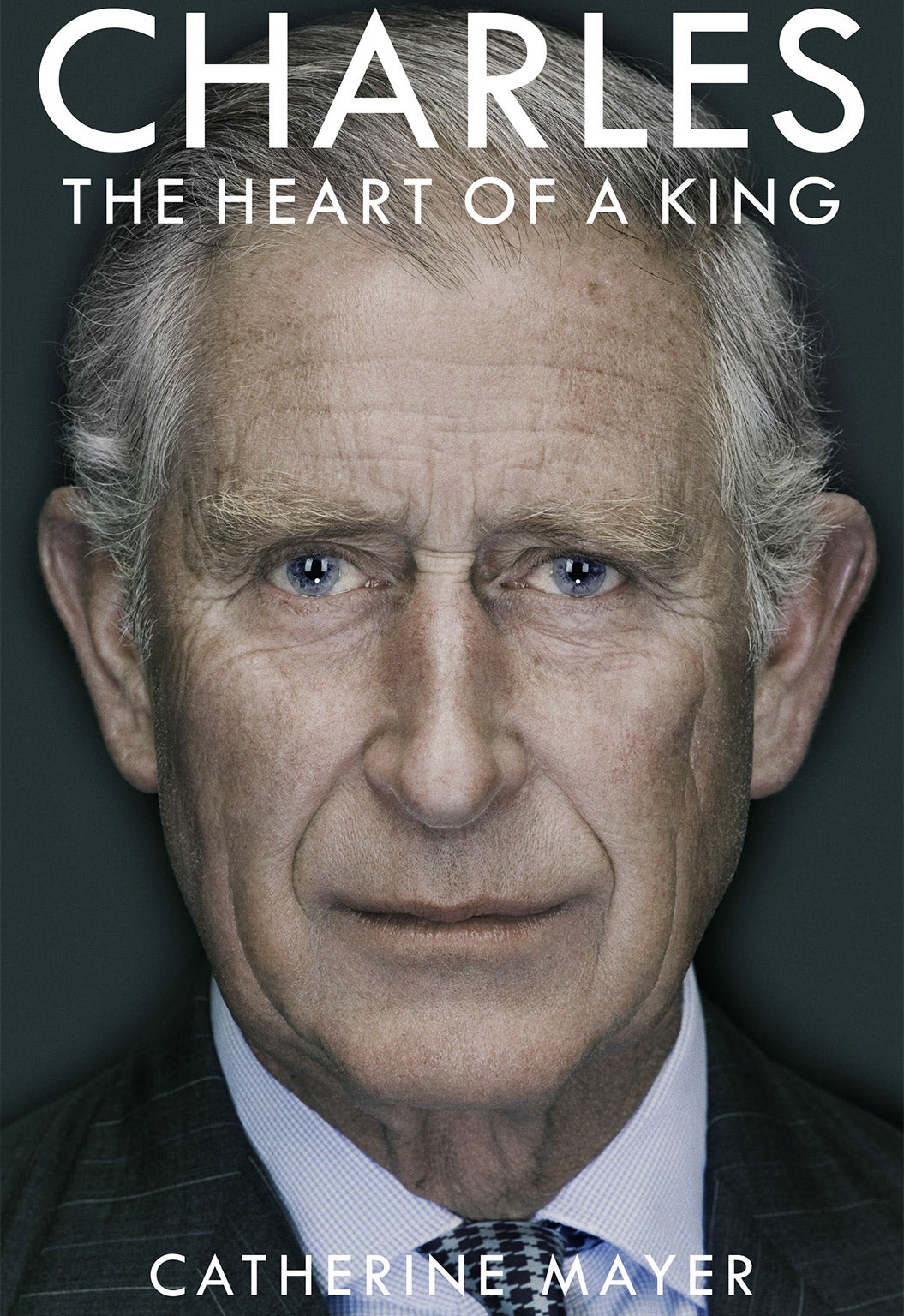

Charles: The Heart of a King by Catherine Mayer, book review: New biography strives for balance but exposes weaknesses

Mayer's book is respectful, sympathetic and surprisingly positive but does not omit uncomfortable facts or polite criticisms

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There could be no better advertisement for this biography of the Prince of Wales than the brickbats hurled at it from Clarence House. Royal aides have stressed that the book is unauthorised, and that Catherine Mayer only had one brief interview with the Prince and limited access to his friends, which explains its misconceptions. But Mayer herself acknowledges that she was kept at arm's length and found it hard to penetrate the wall of silence surrounding Charles.

And her account of his life actually strives hugely to achieve balance. A sustained piece of higher journalism based on diligent research, it is respectful, sympathetic and surprisingly positive. But it does not omit uncomfortable facts or polite criticisms.

However, too much has been made in the press of the book's so-called revelations. It contains little that is new, though one is glad to learn that Charles sees himself as Baldrick in the television series Blackadder. Reams have been written about Prince Philip's impatience with his eldest son, whom he tried to toughen up by brutal educational means and still subjects to more kicks than ha'pence. We have long known that both Charles and Diana were desperate to pull out of their wedding but thought that they had to fulfil public expectations – her face was on the tea-towels.

It's amusing to hear that an inmate of Clarence House nicknamed the place Wolf Hall but it is hardly news that the Prince's court has been a hotbed of intrigue, vendetta and sleaze. In a book which Mayer does not cite, an equerry of the late Queen Mother, Colin Burgess, painted a vivid picture of the Tudor-style infighting. He recounted how Charles's valet, Michael Fawcett, who shouted and screamed at other members of staff and was "an absolute bloody nightmare to work for… somehow managed, with the trust and full knowledge and cooperation of the Prince, to build up a huge power base which threatened the whole employee structure within St James's Palace".

Mayer, who is Editor at Large on Time magazine, does not provide a chronological narrative of Charles's life. She covers it discursively, even diffusely, with detours into related subjects such as the phone-hacking saga and the Parliamentary expenses scandal. An oft-told tale certainly emerges: the unhappy childhood, the Goon-ish adolescence, the flings with Charlie's angels, the search for a purpose, the disastrous marriage, the Camillagate tapes, the controversial causes, and the settling into uxorious middle age. But Mayer, who followed the Prince round, observing him on tour in Wales and Canada, concentrates on his work and his opinions.

She dilates on his unique prestige as a British ambassador, particularly in the Arab world, while recording his dislike of being used to market weapons to the Gulf States. She is full of admiration for charities such as the Prince's Trust, while acknowledging they are run in an amateurish fashion. His architectural crusades, with their talk of monstrous carbuncles and steel dustbins, come in for more stick. Not only have they damaged the careers of architects such as Lord Rogers but they are based on "timeless" principles which are unsatisfactory in practice. But Mayer thinks there is something to be said for Poundbury, the Prince's pastiche Georgian village near Dorchester, though she doesn't mention that locals call it Charlieville.

She does note that all his campaigns, especially those for holistic medicine and organic gardening, have been informed by a quasi-religious desire to realise an "invisible grammar of harmony". In fact, Mayer pays Charles the extravagant compliment of taking his ideas seriously. She describes as a "philosophy" what might better be characterised as a mish-mash of mumbo-jumbo – the Prince stresses how important it is to recognise the "beingness of things". Still Mayer does admit that Charles was easily duped by charlatans such as his mystical mentor Laurens van der Post (as well as monsters like Jimmy Savile). And she quotes Will Hutton's astute comment that Charles is really arguing that hereditary monarchy is an implicit "part of the natural order".

Charles divides where his mother unites and he intervenes in politics in a way that many see as unconstitutional. Republicans regard him as their king of trumps, reckoning that Queen Elizabeth's death will provide the best opportunity for promoting an elected head of state. Mayer endorses this assessment, which is highly dubious given the surge of royalist emotions that will inevitably be generated by the funeral and the coronation. However, as a monarchist herself, she concludes by advising Charles about how to keep the throne: embrace transparency, especially in financial matters; renounce special privileges, such as the Prince of Wales's extraordinary right to veto proposed legislation affecting his own interests; and find cheaper ways to project majesty.

Prince Charles will reign in a different fashion from his mother, Mayer predicts, since he feels so passionately about his causes. For better rather than worse, she thinks, he "will never be neutral". It's a rash aspiration, last canvassed by Edward VIII. Above all it ignores Walter Bagehot's ominous warning about the danger of having, "upon a constitutional throne, an active and meddling fool".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments