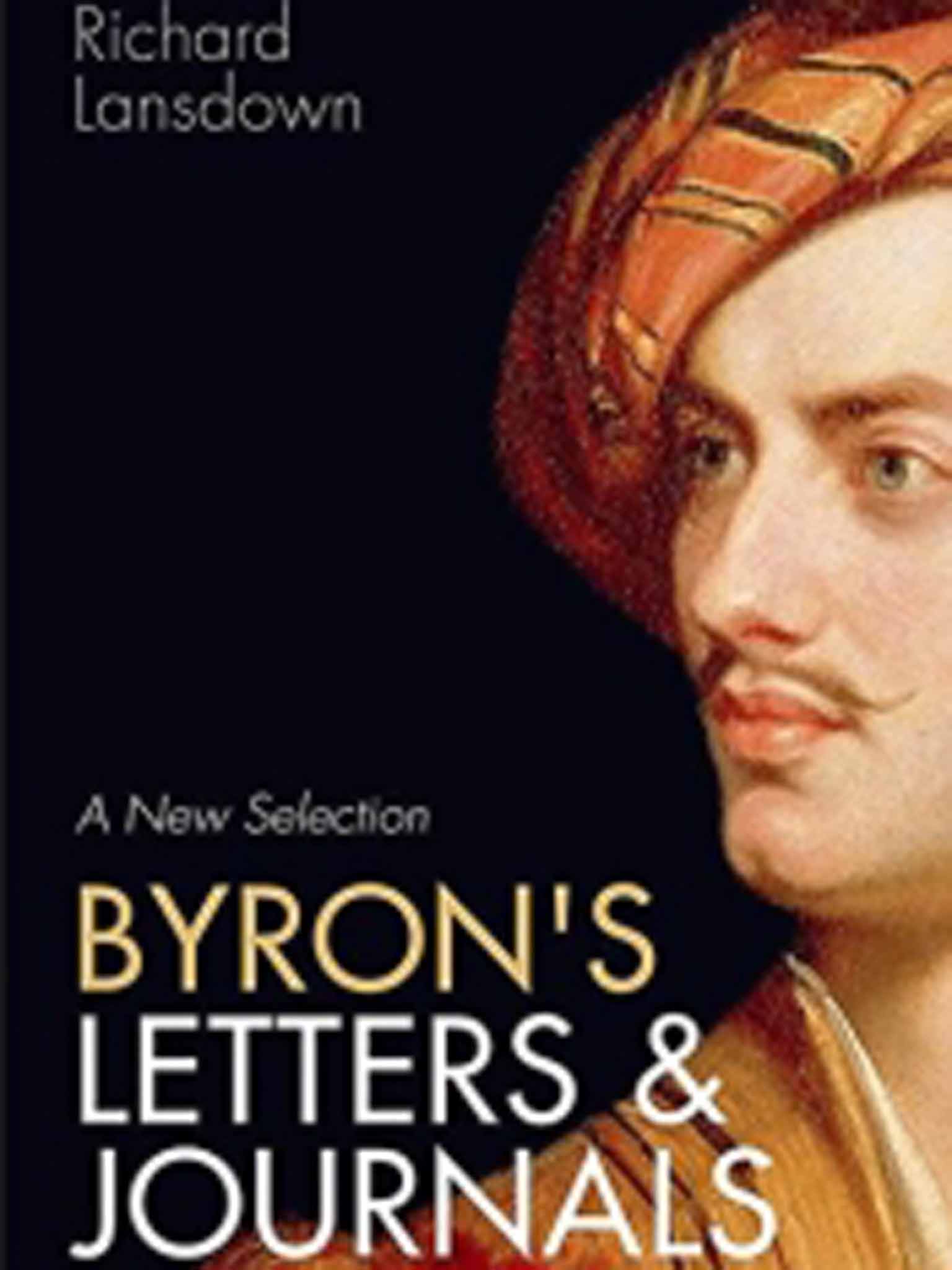

Byron's Letters and Journals, a New Selection edited by Richard Lansdown - book review: What's not to like about this selection? Just its author …

The 500-odd footnoted pages Lansdown has selected are aimed not at scholars and students but at intelligent readers of literary prose

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Of all genres, letters and journals are surely the most informed by their author's own character. Virginia Woolf's Diaries are full of a brilliantly captured sensibility, while Dylan Thomas's Letters are by turns seductive, sentimental and full of serious writerly concerns. We claim to read these intimate forms for their prose style. But of course they also feed the proprietorial sense we have of our favourite writers.

A century earlier than Woolf, another "roaring boy" raced, like Thomas, toward an early death. With his friend Percy Bysshe Shelley (and John Keats, whom he despised) Lord Byron was a second-generation Romantic poet, forced into European exile. The epic sentimental educations of his Childe Harold (1812-18) and Don Juan (1819-24), set largely on that continent, created the archetype of the rebellious, charismatic "Byronic hero" that today saturates popular culture. The 13-volume complete Letters and Journals is out of print. So Richard Lansdown's New Selection of Byron's informal writings seems both attractive and overdue.

Unfortunately, it is very hard to like Byron. Profligacy, sex addiction, callousness about the dying Keats, the way he separated one of his illegitimate children, Allegra, from her mother and, when tired of her, committed her to the institution where she died: these are familiar facts. What shocks is how he addresses them. "I have written you the vilest and most Egotistical letter that was ever scribbled," as he deprecates, in a moment of false modesty, to Lady Melbourne in September 1812.

The 500-odd footnoted pages Lansdown has selected are aimed not at scholars and students but at intelligent readers of literary prose. He argues that they constitute high literary achievement because they are full of life, and "the works of an everyman". It's certainly true that Byron's life rushes through them. The effect is of haste and thoughtlessness. This is the singularly unconflicted expression of privilege: a psyche for whom everyone else is merely instrumental.

Relentless sexual boasting, including to his mother, dismisses conquests including those we'd regard as underage, servants, prostitutes, and others in no position to say no to an English lord. In the biographical summaries which introduce each section Lansdown is, naturally, a Byron apologist. Yet on the page, as in life, Byron resists his friends' best attempts to sanitise him. Was he "an everyman"? We can only hope not.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments