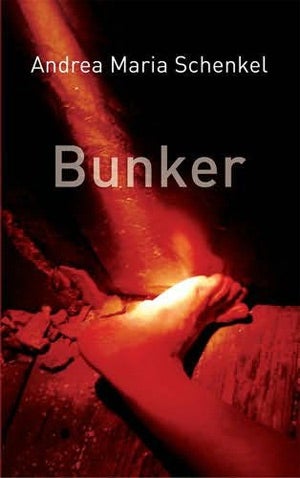

Bunker, By Andrea Maria Schenkel, trans. Anthea Bell

Reality bites in this dark, vivid thriller

Andrea Maria Schenkel specialises in nerve-shatteringly realistic fiction. In this book we're nose-to-nose with psychopath and victim alternately. Monika has the nightmarish experience of being bundled into a car and taken to an old mill hidden in a forest. Here she is trapped first in an attic then, after attempting to escape, kept underground.

Her captor is a monster, and she is totally innocent. But as the narrative intercuts between the two, the reader realises that there is a history here. Both characters draw on their childhoods: she on the murder of her brother and the trial at which her evidence convicted the accused; her attacker on the vicious cruelty with which he and his mother were treated. Were their pasts intertwined?

The exploration reaches deeper, back to the bunker in the mill cellar, built by the captor's father. He claimed to have been half-buried underground during the war, and later created an underground refuge. Only much later does his son realise that the wartime experience must have been a total fabrication; that what his father sought was a hiding-place from retribution for his own crimes. His capture of Monika is a psychological regression.

But Monika is a courageous woman, engaged in a constant struggle against her captivity. At first she conducts a physical battle in which she manages to injure her hands so badly that she needs the care of her captor and the drug he pumps into her to relieve pain. There follows a bizarre relationship, retold from both sides in interlocking dual versions of events.

Monika begins a process of psychological manipulation. She proposes a plan which will involve them both as they entice someone else to the mill: an outsider to the strange relationship growing between the two. But that plan goes awry too, and we learn the brutal final twists of the captor's boyhood struggle against his father.

The screw is further turned by occasional glimpses of an autopsy in which the pathologist is coolly recording the progress of a forensic investigation. But we have no clue as to whether the body is that of the prisoner or the captor. This slender novel works as powerfully as Bernhard Schlink's The Reader as an extraordinary paradigm of the effects of war on the German psyche, and is as intense an experience.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks