Book of the week: Chavs: the demonization of the working class by Owen Jones

A war against the poor

The most important public document of the last century was arguably the 1909 Minority Report of the Royal Commission into the operation of the Poor Law. It was a landmark in the abolition of the workhouse; a cornerstone of the future welfare state. The authors - including Beatrice Webb and future Labour Party leader George Lansbury - refused to accept the notion of the "undeserving poor"; of a feckless, lazy mob. The evils of poverty were deemed to be socially determined; not simply the product of personal idleness.

Since this extraordinary document, a fundamental political tussle has periodically occurred. At moments of economic crisis, the poor are reintroduced as degenerate, so as to strip back the hard-fought safety nets secured by previous generations. We focus on an underclass as if to obscure more fundamental economic issues: a "kiss up, kick down" politics.

Parts of both left and right trip into eugenics. Today, the poor pay for the bankers' crisis, while everyday being demonised across the media world. Somewhere along the line, we join the dots and the single mother on welfare, with a handful of kids from various long-gone blokes, is culpable for the economic crisis. Occasionally, an intervention seeks to buck the trend and defend the seemingly indefensible. I had been tipped off about Chavs, and was keen to have a read, having had the book pitched to me as an attempt to help rehabilitate a modern class politics. It does stand as a bold attempt to rewind political orthodoxies; to reintroduce class as a political variable.

The book exposes class hatred in modern Britain. In the public domain of news and culture, within the arc of some 30 years, a once-proud working class has been residualised into a violent, degenerate, workless mob. Think Hillsborough. Chavs charts the political demonisation of this once-noble group through the material transformations of the early 1980s and the collapse of manufacturing work. Think Thatcher.

I got nervous for the first couple of pages. Owen Jones responds to some pretty mild class stereotyping at a left-wing London dinner party by resolving to discover more about this intensifying hatred. Alarm bells start to ring at the prospect of what might be heading our way: a couple of hundred pages of class tourism, with a bit of Orwell and Toynbee Hall thrown in. To his great credit, he resists this and drills right into the subject.

Jones focuses on the case of Shannon Matthews, the child who disappeared in February 2008, to expose the way the rich and the powerful define the nature of contemporary working-class existence. Scores of Dewsbury Moor residents raised money, volunteered and searched for the young girl before she was discovered on 14 March, drugged and hidden in a divan bed at the home of a relative. From this moment, the community itself was seen through the prism of Shannon's mother Karen. Their efforts were ignored as a picture was painted of a lawless, morally corrupt, workless nation. The press and politicians used the case to shine a light on a politically expedient, dystopian vision of "Broken Britain", dominated by a feral underclass. Valiantly, Jones unpacks this caricature step by step, posing the appropriate questions as to why the people are being so demonised. Cui bono?

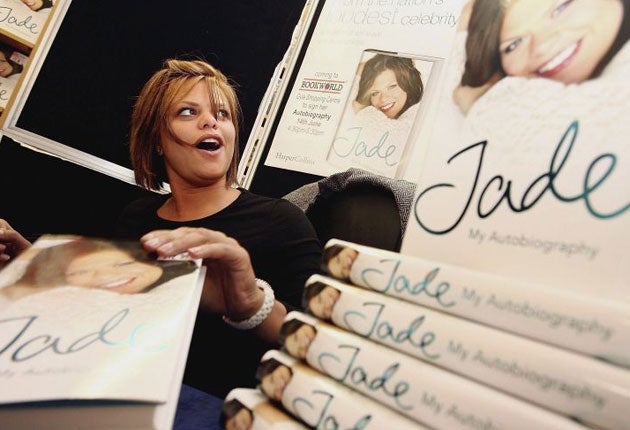

The case of Shannon Matthews gives him his route into a wider discussion of day-to-day chav bashing and class hatred: Little Britain and Jeremy Kyle; gym classes sold as "chav fighting; the promotion of "chav-free holidays"; Harry Enfield and Shameless; the Little Book of Chavs, Wife Swap and the website Chav Scum. The list culminates in the appalling treatment of Jade Goody, possibly the high point in the text. The book is very easy to read; it moves in and out of postwar British history with great agility, weaving together complex questions of class, culture and identity with a lightness of touch. Jones torches the political class to great effect. Conservative class conflict masquerading as liberalism; New Labour's desiccated notion of aspiration; what we stylise as "Middle England"; the class composition of the commentariat and government: all are pretty easy targets, but the points are well made. Especially strong is his critique of liberal multiculturalism, whereby without the currency of class grievance we balkanise politics through identity and, sure enough, the BNP or English Defence League flourish.

Jones tours the country, but not as the political tourist we feared after the dinner party piss-takes. Rather, he gives voice to a working class disenfranchised by neoliberalism and electoral calculus. As an aside, I would like to know his views on electoral reform. He does not patronise. He gives voice to aching economic and cultural loss and pain; to a profound sense of abandonment, and a need for hope and belonging.

All roads are leading us to a different type of politics: less liberal and materialistic, communitarian and ordinary, class-based, anchored in everyday experience. Dylan Thomas once said that the Labour movement at its best was both "parochial" and yet "magical".

So we end up with the politics. Apart from a fleeting aside about the minimum wage and public-services investment, there appears no redeeming element to 13 years of Labour rule. There is no notion here of a contested terrain within government; or of battles for influence or ideas; or of the political possibilities with Blair and Brown (so as to better understand the failures); or of political nuance and the creative possibilities we might attach to capitalism, not just its destructive capacity. Answers lie in these spaces. Yet here Labour people are either authentically bad: "right-wing", "Blairite", "maverick" etc, or authentically good: "left-wing", "union-sponsored", "radical" and the like. The simple task is to recapture Labour's working-class voters, lost through its embrace of neoliberalism.

Yet you cannot have it both ways. Put simply, the working class has been smashed economically. Its culture is being destroyed and its families are literally disintegrating. There is no simple political on/off switch here. This book details these wretched processes and gives voice and renewed dignity to some of the victims. But this is tough stuff.

The policy proposals are actually strong: on housing, manufacturing and labour law, for example. But the crisis for the left will not be solved by simple policy. It is a crisis of character and identity. The trouble for Owen Jones is that he appears unable to escape a reductive factionalism; of an absolutist politics that inhabit his remedies. I might well be doing him a disservice, but where are the coalitions to fight this commodification and destruction?

Currently, in and around Labour, the fight appears to be between a progressive cosmopolitanism and the neoliberal remains of what became of Blair and Brown. The solution lies in rebuilding an alliance of these parts with one grounded in the complex, everyday, parochial experiences of working people; one built around the dignity of the human being, and a modern sense of solidarity and compassion. This book is a very important part of that political movement - if the author wishes it to be.

Jon Cruddas is the Labour MP for Dagenham and Rainham

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks