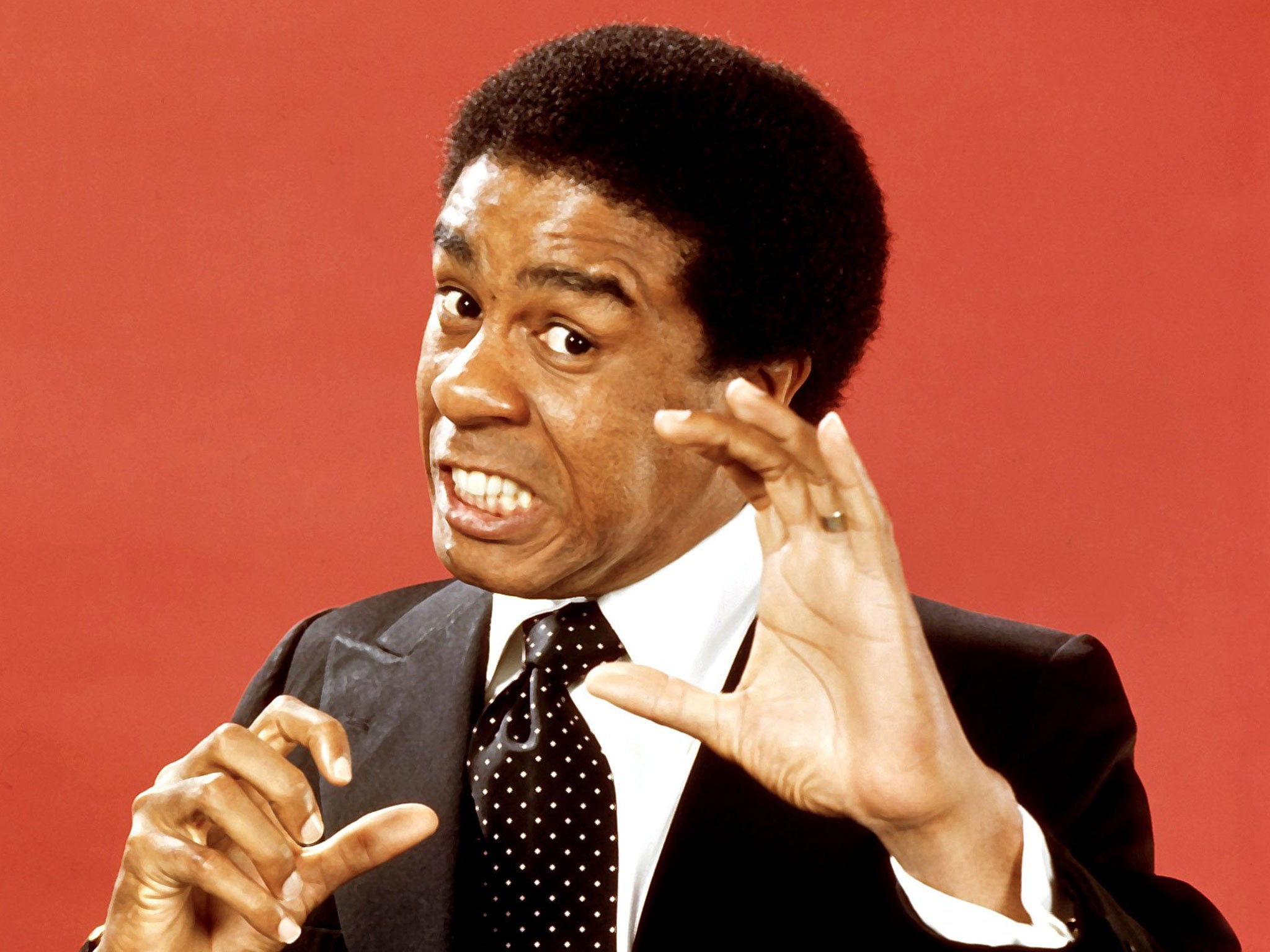

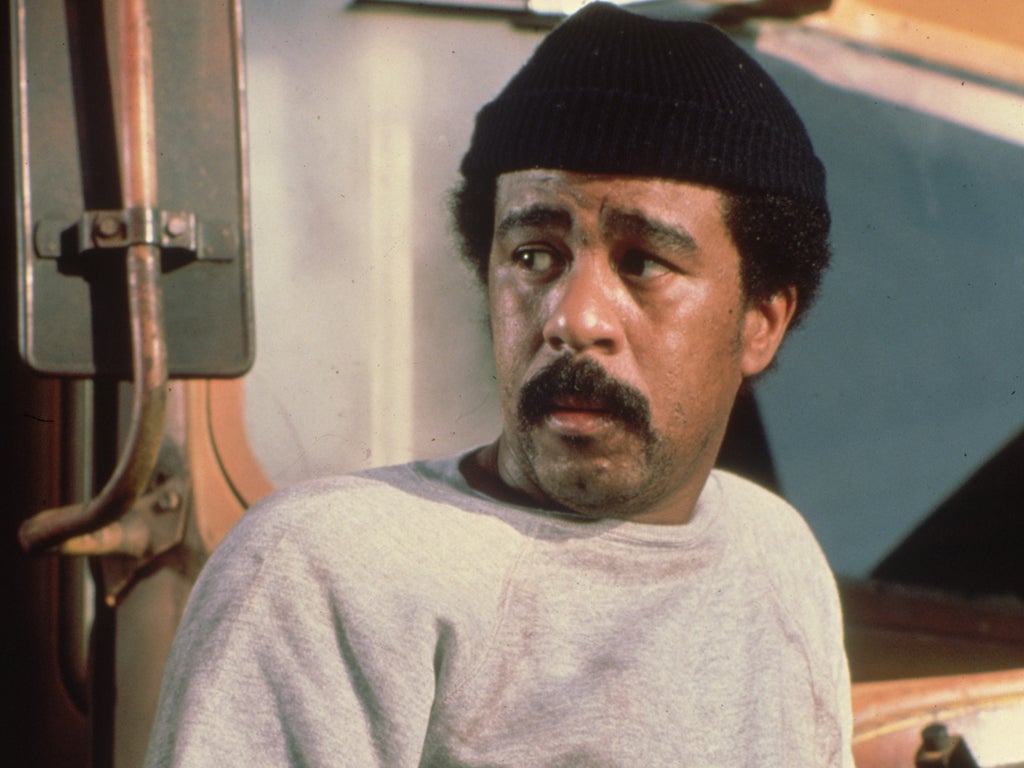

Becoming Richard Pryor by Scott Saul, book review: Magisterial biography of a comic genius

Brilliantly reveals the glorious highs and lows of Pryor’s life

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At one point towards the end of this magisterial biography/ paean/mea culpa for Richard Pryor, the author Scott Saul refers to Pryor as “flirting with oblivion”.

A great phrase and the actual subtitle of this almost 200,000-word opus which dissects, and puts under the microscope one of the great comic geniuses of the 20th century.Saul begins the story of this African-American monstre sacré with his grandmother, Marie. A strapping woman of almost six feet, Pryor created her later in life, as some soul food-cooking black mid-western version of Betty Crocker.

Later in his career, after he had become a superstar, Richard would bring her on to one of America’s most popular afternoon shows, where he was a regular guest. There she would demonstrate her cooking prowess and crack jokes, accompanied by smiles all around.

She had been, in fact, a successful madam, the denizen of a whorehouse which she ran with ruthless efficiency and where Pryor grew up. His own propensity for beating up the women who loved him, stripping them naked and running them into the street, must have come from Granny Marie. She was not averse to beating, in full public view, the women who worked for her.

Pryor’s father, Buck – grandma’s son – worked for her and so did Richard’s mother. Surrounded by pimps , sex workers, their white customers; and assorted flotsam and jetsam of a deeply sordid existence, Pryor sought refuge in cartoons and his own brilliant imagination and courage. He believed in himself and his ability to transcend the kind of childhood that could have created a murderer.

Late in life, he created a tale of himself as one of 11 children, when in truth, those 11 personalities all lived inside of him. His genius lay in the fact that he loved them all: the winos; the pimps; the jack-leg preachers; the truth-tellers like his masterpiece “Mudbone” who encompassed the entire breadth and depth of the African-American experience in one routine.

Pryor, in and out of school, was “discovered” by a young black teacher he always referred to as “Miss Whittaker” who saw his gifts, knew his heart, and gave him a chance at the local youth centre.

He fled his hometown of Peoria, Illinois – on the outside a fairly non-descript town not far from Chicago, but in the 1940s and ’50s a veritable Sodom and Gomorrah of vice – to the US Army in Germany where he thought he might find freedom.

Unfortunately, unlike Colin Powell who was stationed in Germany at the same time, Richard wound up in a part of the country controlled by Southern whites, who had turned it into a kind of Mississippi.

To avoid getting himself dishonourably discharged for various infractions, Pryor left, and decided to make himself what he dreamt of being: an actor. And a star.

Saul ably dissects the New York comedy scene of the early 1960s as it emerged from the era of the so-called sick comics such as Lenny Bruce into an era that embraced improvisation and the avant garde in clubs such as The Improv.

Richard could follow a character he created all the way to its natural conclusion and beyond. His childhood movie idol, the cowboy star Lash LaRue who dressed all in black, complete with black horse and black hat; could jostle with his other idol Jerry Lewis; and the denizens of his grandmother’s brothel, mixed in with the child that Richard still was inside, and who never ceased staring out at the world, wondering who he was.

Pryor’s great rival and great friend, Bill Cosby, emerges as another revolution in comedy, but the counter to Richard’s. Cosby never brought his colour onstage; he always presented himself with a supreme confidence and it is against him that Pryor set himself. Cosby was jazz: smooth and confident. Pryor was the blues: erratic; tragic; full of magic and the unspoken, searing with rage and a hidden tenderness. Richard wanted to bring blackness onstage; the inner life of the ordinary black man faced with the reality of racism, poverty and fear.

The “N-word” became for Pryor both a badge of honour; an accolade even given to white people he thought “got it”; and a provocation to be hurled out from the most respectable settings.

One of the funniest things I have ever seen on television was one of the many afternoon shows that Pryor guested on in an effort to become a household name, and therefore have the freedom, the money and the revenge against the white man that he craved. The daredevil Evel Kneivel walked onstage with an elaborate cane, a beautiful piece of work. The audience listened in rapt silence as Kneivel described how he would drive his motorcycle over the top of 10 trucks and down a ramp.

After he finished, Pryor asked him: “If you don’t make it, can I have that cane?” The laughter was raucous and embarrassed because once again he had nailed the truth of human nature. It wasn’t about the heroics of the daredevil against all odds. The audience wanted to know what would happen with the cane. The cane was about survival.

Becoming Richard Pryor delves into Pryor’s need for fame, money, authenticity, truth, sex, drugs and his own personal rock ’n’ roll. And he went all the way to the edge.

For example: in his short-lived television show, he assured viewers that he had given “nothing away to NBC” in exchange for complete artistic control. As he smiled reassuringly into the camera, the camera panned down to show his genital area “erased”. And this on American primetime television.

He co-wrote half of the ground-breaking Blazing Saddles film, which launched the new genre of the spoof movie. He brought to television the techniques of the New York comedy clubs that helped to launch Saturday Night Live. And he got through industrial amounts of cocaine and cognac to make it all happen.

On the edges of this quest for the self are the children Richard never quite parents; the white women he sometimes marries; and always beats up and discards; the white men he challenges and yet – with some of them – he harbours a deep affection; and the “brothers” whose lives, voices, and experience he feels that he has almost a religious duty to explore, and reveal.

And, at the base of all this, lie his very own Addams Family, the people he was born to and who raised him, ensconced in a house of horrors, in fact, and in Richard’s mind, too. The Pryors were people who, somehow, Richard managed to both expose for who they were. And ennoble.

The book ends with the beginning of Pryor’s masterpiece: Richard Pryor Live In Concert in which he breaks new ground not only in comedy, and the African-American experience, but in himself. It is then, that Becoming Richard Pryor reveals itself to be not simply a biography, but the compassionate map of a terra incognita.

Bonnie Greer’s new memoir, ‘A Parallel Life’, is published by Arcadia Books

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments