Battling the Gods: Atheism in the Ancient World by Tim Whitmarsh, book review

Tim Whitmarsh salutes the ancient sceptics who cocked a snook at organised religion

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Nicknamed "the Atheist", Diagoras of Melos was the Christopher Hitchens of ancient Athens. By 423BC, he had attracted enough renown as an anti-religious contrarian for Aristophanes to lampoon him in his comedy Clouds.

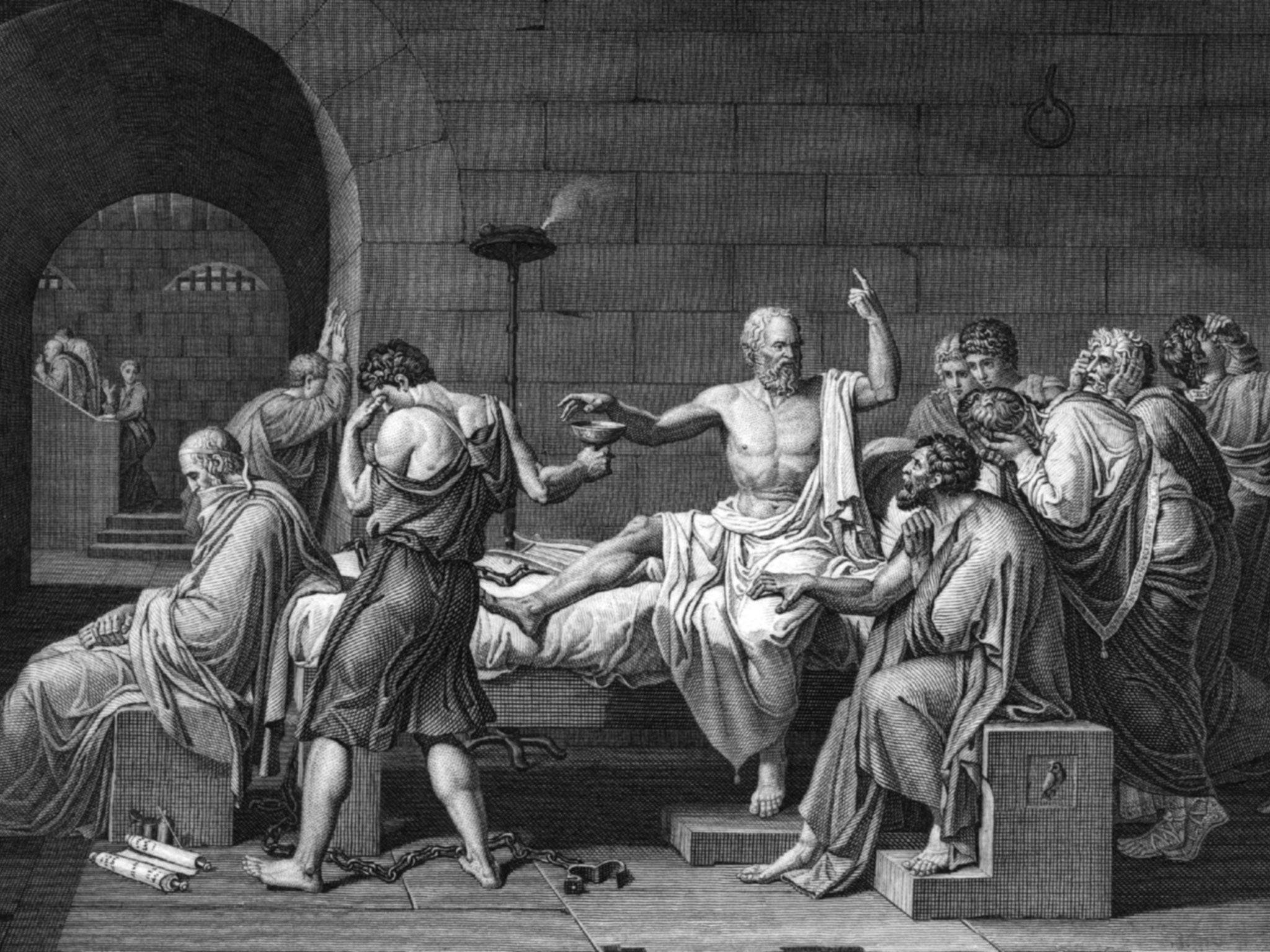

A few years later, the city – strife-ridden after catastrophic wars – began for the first time to persecute subversive spirits. Socrates, also accused of heresy, would become the star victim of this harder line. But long before he downed the hemlock, Athenians erected a bronze inscription offering one talent in silver to anyone who killed Diagoras: a fatwa flung at an impious freethinker. Undaunted, Diagoras revelled in this notoriety.

Tim Whitmarsh wonders if we should call him "the first person in history to self-identify in a positive way as an atheist". Or the first that we know about? As this illuminating book makes plain, the victors write history – and organised believers triumphed in the West. Even our terms for those who reject monotheistic deities – pagan, polytheist, or "atheist", which originally meant "god-forsaken" – "stack the deck in favour of a Christian world-view". The Greeks, however, followed by the Romans, wrote copiously about outsiders and mavericks on the fringes of respectability. Among them were "eccentrics, deviants, miscreants and sceptics".

So we know a lot about the scientific materialists, satirical scoffers, philosophical questioners and out-and-out secularists who punctuate the history of Greece and Rome. Whitmarsh, who now fills the big shoes of historian Paul Cartledge as Leventis professor of Greek culture at Cambridge University, restores them to life in this lively, learned and cliche-busting book. In a work of openly committed scholarship, he aims to rescue ancient doubt and disbelief from a long tradition of slander and opprobrium. And he has an eye-opening story to tell.

If we accept that the Israelites in Jerusalem dumped all other gods in favour of the jealous, unique Yahweh sometime after 539BC, then by that period Xenophanes of Colophon had already recorded his scepticism. In other words, atheism may be "at least as old as the monotheistic religions of Abraham". Let no one brand a non-believer as some post-Enlightenment freak, or atheists as modern weirdos who are "incomplete in their humanity".

From the defiant human heroes who fought the gods in Greek myth to the experimental rationalists of Miletus; from the pre-Socratic pioneers of atomic theory to the fury against faith staged in Athens by Euripides, Whitmarsh tracks doubters over eight centuries, across the Mediterranean world. Much of the evidence comes from hostile sources. In Laws, Plato takes aim at these "clever modern types". By the era of celebrity non-believers such Sextus the Doctor and Aetius, in the second century AD, atheism in the strict modern sense "had acquired full legitimacy as a philosophical idea".

If Whitmarsh's case has a flaw, it is that he too brusquely enfolds older notions of agnosticism and philosophical doubt into the atheist hypothesis. Greece and Rome had plenty of discreet thinkers who could see the social point of faith, but had no use for dogma. Several eloquent witnesses belong in this camp. As Pliny the Elder wrote, "God is one mortal helping another".

Not that the Christians who took control of the Roman Empire cared about the nuances of doubt. In the fifth century AD, our wars of faith began. They have not finished yet.

Faber & Faber, £25. Order at £21.50 inc. p&p from the Independent Bookshop

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments