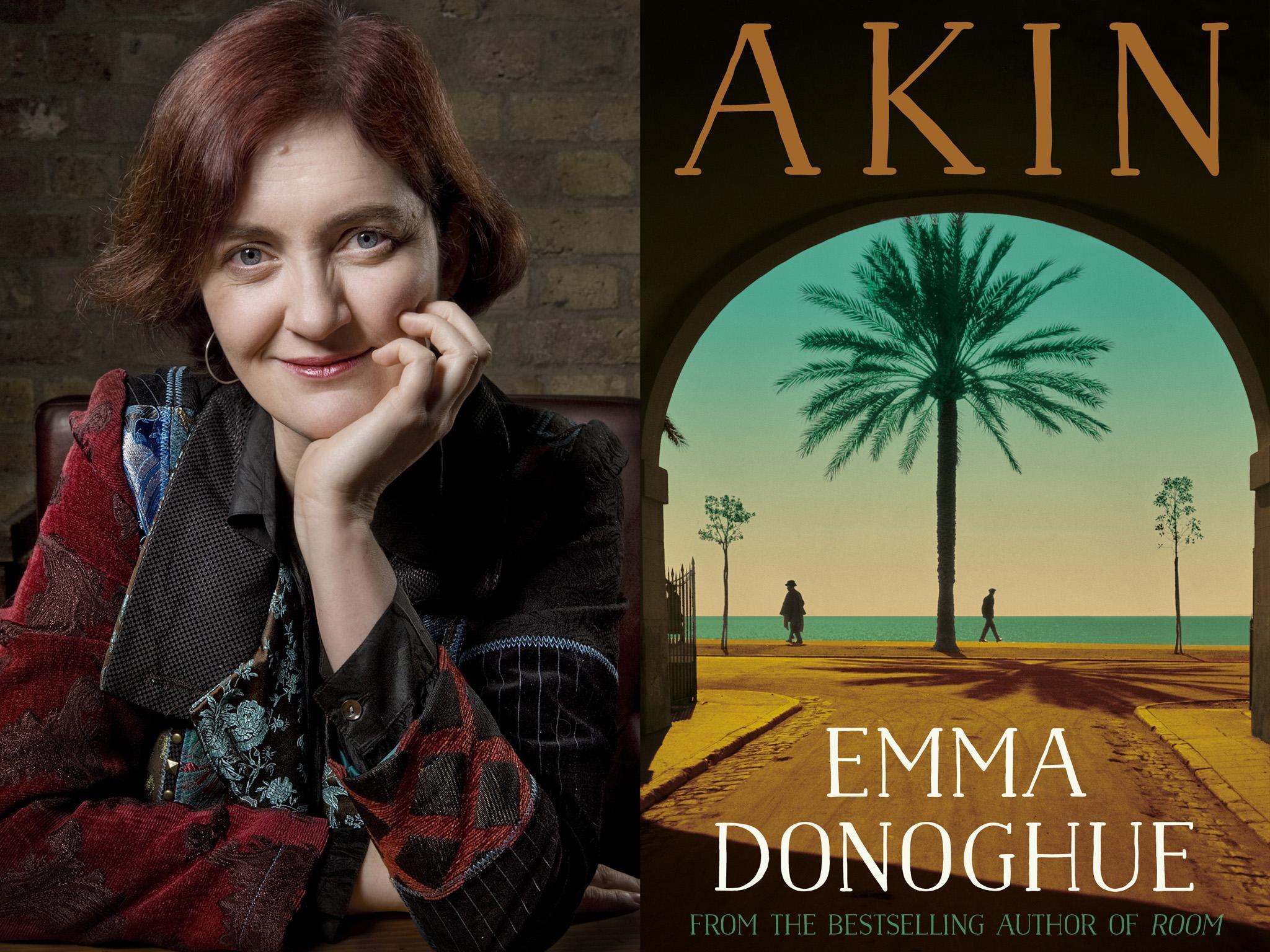

Akin by Emma Donoghue, review: A keenly observed novel about family that is a complete departure from Room

The Irish-Canadian author’s first contemporary novel for adults since ‘Room’, which was a finalist for the Booker Prize in 2010, is a profoundly human portrayal of a life disrupted by the opioid crisis

If you found Emma Donoghue through Room, the 2010 bestselling novel that landed her on the Man Booker Prize shortlist, then you should know that Akin, her first contemporary novel for adults since Room, is very different in tone, style and substance. This isn’t in any way an indictment on either novel – if anything, the differences between the two only highlight Donoghue’s range – but knowing this might enable you to appreciate Akin for what it is: a touching, keenly observed novel (if less suspenseful than Room, told from the persepective of a boy held captive with his kidnapped mother), examining the complex dynamics of family.

It all begins when Noah (or Noé, as he was known during his childhood in France) meets Michael, his great-nephew, who’s in need of a new caretaker. Michael’s father, Victor (Noah’s nephew) died a year and a half prior, his veins “full of heroin and fentanyl”. His mother, Amber, is behind bars after the police “found crack cocaine, meth, and oxycodone in her car”. His grandmother Ella, who had been entrusted with his care, has just died. This all means that Noah, who has never even met his great-nephew, must now act as a temporary guardian for the 11-year-old boy. Neither Noah nor Michael is particularly pleased with this arrangement, though Noah – an almost 80-year-old, retired, widowed professor who’s never had children of his own – feels a pull of duty towards his relative.

Noah, as it happens, was just about to fly from New York City, where he occupies a tastefully decorated apartment on the Upper West Side, to Nice, the city of his childhood, where he was hoping to reconnect with his roots (and possibly elucidate the mystery of nine enigmatic photos found in a box of his late wife’s belongings). One expedited passport request (for Michael) later, the 11-year-old joins his great-uncle on his transatlantic flight – leaving the beauty of their mismatched pairing to unfold from here on out.

Worlds collide as soon as Michael, who’s from “one of the last pockets of Brooklyn resistant to gentrification”, enters Noah’s prim flat on the Upper West Side. Worlds most definitely keep colliding as Noah tries to enjoy the fine delicacies France has to offer – while Michael, who’s never left the US (and possibly New York City) before, understandably struggles to adapt to his new surroundings.

Akin, in many ways, is built upon everything that sets Noah and Michael apart. Noah’s relatively cushy background (he’s a wealthy academic and the descendant of a famous photographer, but there’s no forgetting that his mother sent him away from France to the US while Italy, then Germany, invaded his native country during the Second World War) contrasts with Michael’s life in poverty, where his menus depend on what’s left at the food pantry, his most prized possession is a pair of Nike sneakers his grandmother bought for him on layaway, and the opioid crisis that snatched both of his parents from him.

And yet, for all the brilliance in Donoghue’s mismatched pair (every time we might be tempted to find Michael slightly annoying, she’s a master at showing us, and reminding us, that he’s just a child raised with virtually no stability due to forces far beyond his control), the novel is at its strongest when it highlights the resemblances that unite Michael and Noah. These go from the relatively mundane (Michael, much like Noah’s ancestor, seems to have a knack for photography, except he chooses to explore it through his smartphone rather than an old camera) to the more profound (both are wrestling with the uncertainties of their families’ lives). There’s strength in their pairing, too, as Noah might know a lot, technically, about the world and its history, but Michael is in many ways better versed than him when it comes to understanding the contemporary way of things.

Through the mysteries of Michael and Noah’s respective upbringings (Noah wrestles with the possibility that his mother might have collaborated with the Nazis, while discovering that Victor and Amber’s plight might be more complex than expected), Donoghue delivers a profound reflection on family secrets and the way they shape our current identities. Her profoundly human portrayal of Michael elicits a crucial form of empathy for the lives disrupted by the opioid crisis and raises questions on its impact on generations to come. All this makes Akin an important, touching novel that stays with you long after you’re done reading it.

‘Akin’ is published on 3 October by Pan Macmillan in the UK (£16.99) and is out on Little, Brown in the US ($28)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks