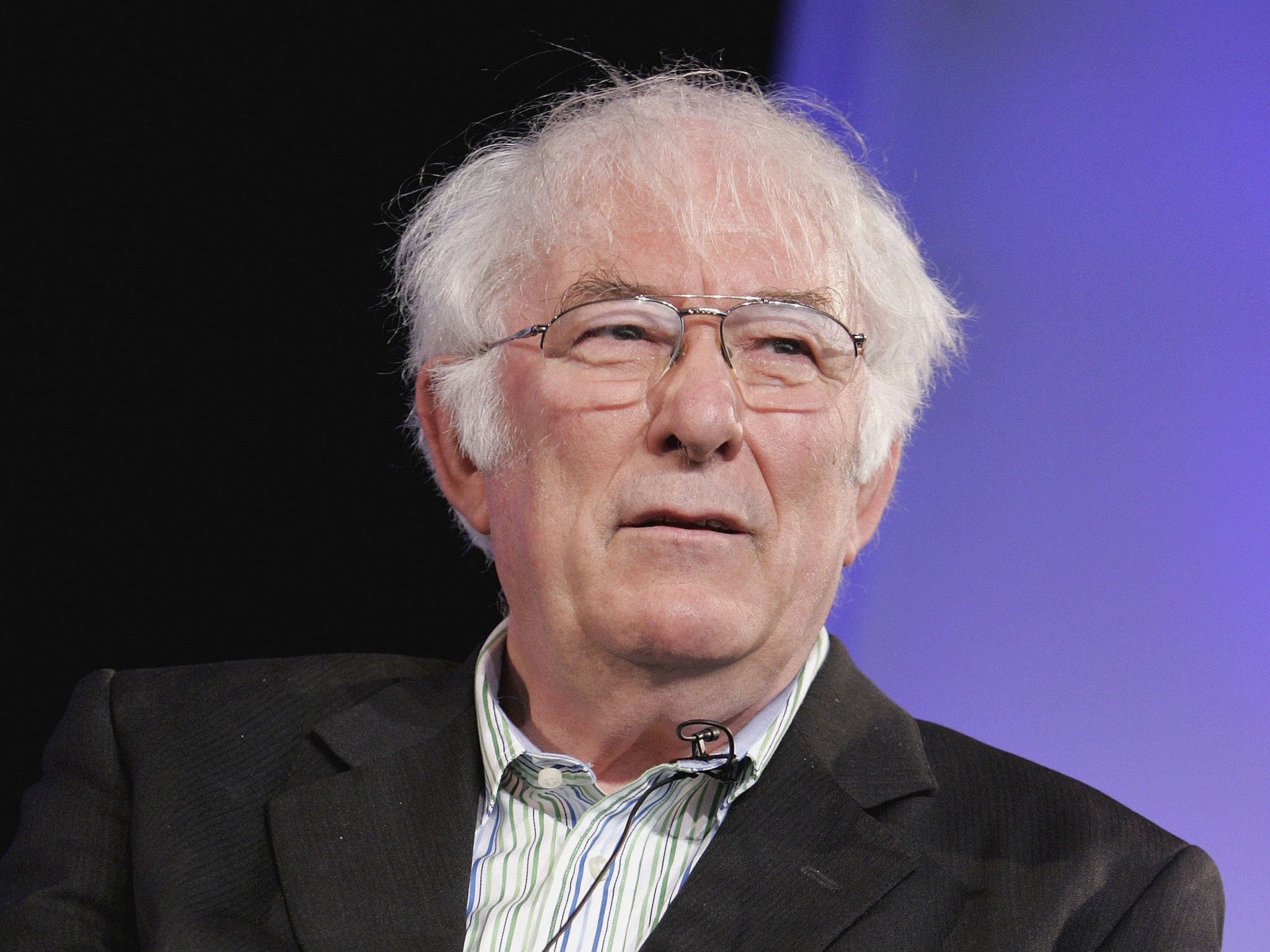

Aeneid Book VI by Seamus Heaney, book review: Powers of the underworld

Seamus Heaney left a final gift to readers - Aeneas's account of his travels in the land of the dead from Virgil's epic

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In poetry, the word "translation" covers a range of approaches. They include prose cribs designed to convey basic sense; then attempts at faithful renderings in verse, often made by scholars rather than poets, often stronger on virtue than interest; next, imaginative recreations of the original, in which the English Renaissance is particularly notable; and finally what are called "versions", often made by poets who don't know the original language but work through intermediary prose texts and discussion, where the resulting poem may have undergone a considerable degree of transformation. Of course, each case is individual.

By and large, all these methods are ways of doing honour to the original, though some poets find it harder than others to submerge themselves and submit to a prior claim. Robert Lowell's Imitations (1961) was a case in point. At the time Lowell occupied the kind of eminence later accorded to the late Seamus Heaney. Heaney told a story of visiting Lowell in 1976 during one of the American poet's spells in a psychiatric hospital. He found Lowell lying on a bed reading Latin verse in the original. Lowell declaimed some lines and challenged Heaney to translate them extempore. Heaney professed himself unfitted for the challenge.

But Heaney, like his classically educated Northern Irish contemporary Michael Longley, did know his stuff. He had studied Book X of the Aeneid for A-level Latin at school. His note to this posthumous translation of Book VI of Virgil's epic explains that it is "neither a 'version' nor a crib – more like classics homework," done to honour the memory of his teacher at St Columb's Academy, Fr Michael McGlinchey.

A passage from Aeneid VI appeared in Heaney's 1996 collection Seeing Things. The death of his father in 1996 and the birth of a grandchild in 2007 kept the project current, and at his death in 2013 he left a complete revised text which, though perhaps not his last intended word on the matter, is a rich addition to his body of work. And the subject of Book VI, the underworld, the powers and meanings under the earth, has much in common with the downward questing of many of his poems.

A well on a farm in Northern Ireland, of the kind that fascinated Heaney as a child, could easily be the entrance to Avernus. As Virgil says, "I unveil things profoundly beyond us, / Mysteries and truths buried under the earth."

With this translation, a circle is being completed, a return made to a point of origin. It parallels the movement away and back which is recorded in Heaney's great poem "Alphabets", where the globe in a classroom window becomes the mature poet's vision of the planet. Heaney did not forget where he came from: his version of Aeneid VI is an act of service to the poem and the literary culture of which it is a centrepiece.

Heaney is not tempted to try to improve on the original; instead he renders it with tact and humility, less concerned with spectacular local effects than with an accumulating gravity, though the torments of the damned can be clearly heard: "the savage / Application of the lash, the fling and scringe and drag/ Of iron chains".

Aeneas has escaped the destruction of his native Troy: landed in Italy, he is to discover the full reason for this – that his descendants will be the founders of Rome. Virgil was acutely aware of political necessity: the Emperor Augustus had a short way with poets who offended him, such as Ovid, and the Aeneid operates as a retrofitted prophecy of imperial greatness. As Heaney points out, by the closing passages "the translator is likely to have moved from inspiration to grim determination".

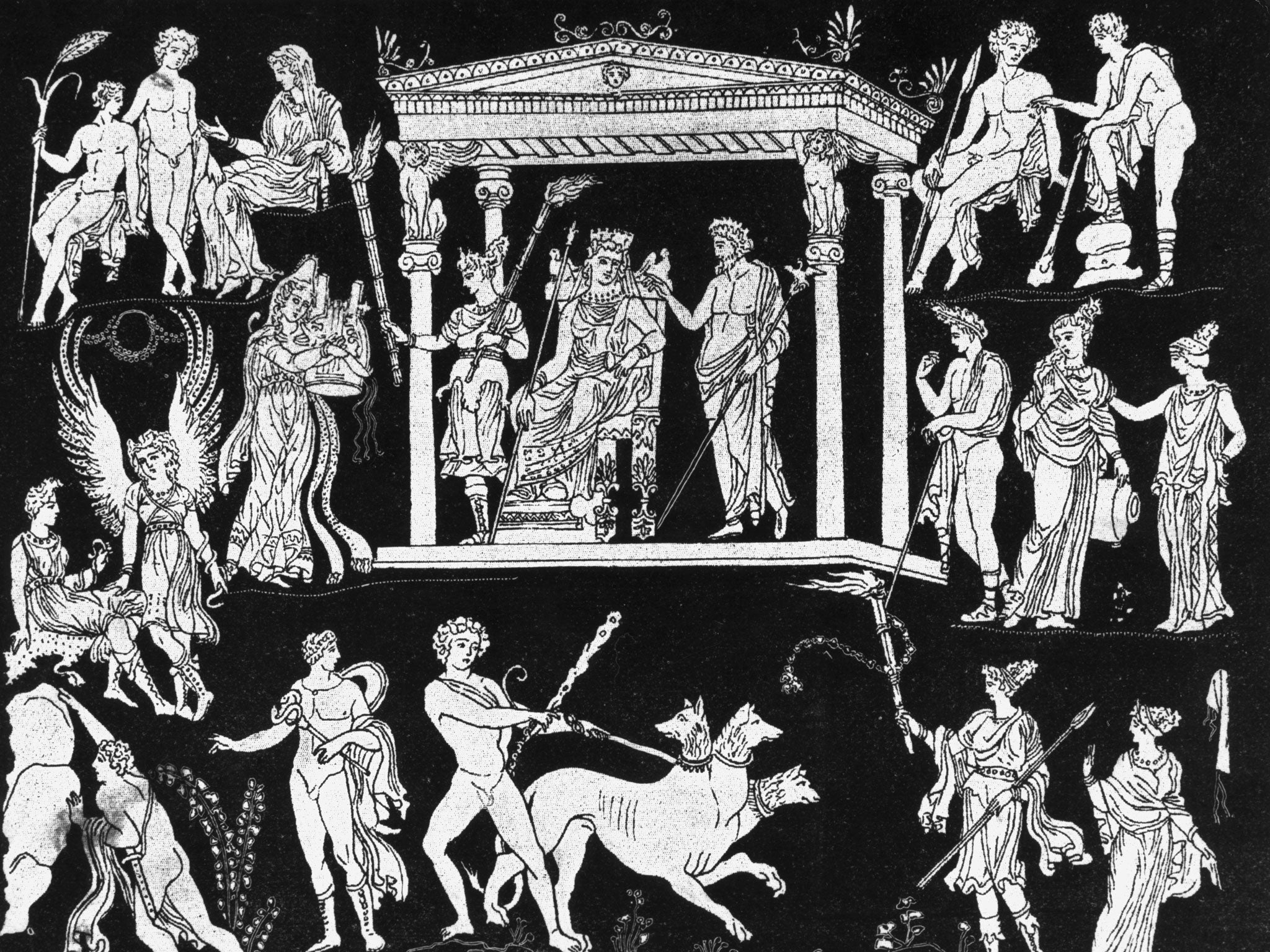

The life of the poem is really to be found in the land of the dead, where Aeneas walks through "a nowhere of deserted dwellings, / Dim phantasmal reaches where Pluto is king – / Like following a forest path by the hovering light / Of a moon that clouds and unclouds at Jupiter's whim, / While the colours of the world pall in the gloom." Dante was to pass this way in the Inferno, guided by Virgil, and would adapt classical mythology to fit a Christian vision, though it is perhaps less the rationale and mechanisms of damnation that compel the contemporary reader than the encounters with individuals in the landscapes of Hell.

One of Dante's greatest portraits is of the Greek hero Ulysses. Here the Trojan warrior Deiphobus bitterly recounts his death and mutilation at the hands of Ulysses and others during the sack of Troy. The brutality of the episode serves to highlight the pathos of Aeneas's meeting with his father, Anchises: "seeing Aeneas come wading through the grass / Towards him he reached his two hands out / In eager joy, his eyes filled up with tears / And he gave a cry: 'At last! Are you here at last? /…/ And am I now allowed to see your face, / My son, and hear you talk, and talk to you myself?"

That far from simple directness and wholeheartedness is hard-won by the poet, and there can be no softening of the blow when "Three times [Aeneas] tried to reach arms round that neck. / Three times the form, reached for in vain, escaped / Like a breeze between his hands, a dream on wings."

The book carries a quotation from Heaney: "The great mythical stories of the afterworld are stories which stay with you and which ease you towards the end, towards a destination and a transition." The"afterworld" looks like home ground, meadows, streams and marshes.

In "Quitting Time", from Heaney's 2006 collection District and Circle, a farmer who might be Heaney's father finishes work in the yard and finds "More and more this last look at the wet / Shine of the place is what means most to him." Amen to that.

Faber & Faber, £14.99. Order at the discounted price of £12.99 inc. p&p from the Independent Bookshop

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments