33 Revolutions per Minute: A History of Protest Songs, By Dorian Lynskey

Why pop stars and politicians don't sing from the same hymn sheet

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The risk of taking their subject too seriously is always high for historians of popular music.

Yet if they don't bother, who will? Dorian Lynskey neatly sidesteps the trap by covering seven decades of tunes already intended as meaningful statements. Despite odd moments of levity, his history of the protest song is generally a grim, often unedifying journey. "Most of these stories end in division, disillusionment, despair, even death," the author admits, with some relish. His definition – "a song which addresses a political issue in a way which aligns itself with the underdog" – and structure are neatly resolved. Each of the book's 33 chapters is hung around a single song, and investigates the wider cultural milieu that produced it.

Somehow it's less surprising to learn that the FBI placed the radical proto-rappers, the Last Poets, under surveillance, than to discover that their independently distributed 1970 debut album actually made the US Top 30. But the 1980s sees a nuclear dread so widespread that Frankie Goes to Hollywood's bizarre "Two Tribes" spent nine weeks atop the charts.

By the 1990s, the naive US feminist students behind Riot Grrrl, a scene better known for manifestos than music, are amazed when a passingly curious press misrepresents their message. Over here, the nascent Manic Street Preachers knew how to impress eager music journalists, but the wider media simply ignored them. As an alternative, there is the bleating millionaire Thom Yorke, more interested in how issues affect him than how he can affect issues. No one does harmless middle-class alienation like the Brits. Ask Pink Floyd or Pete Townshend.

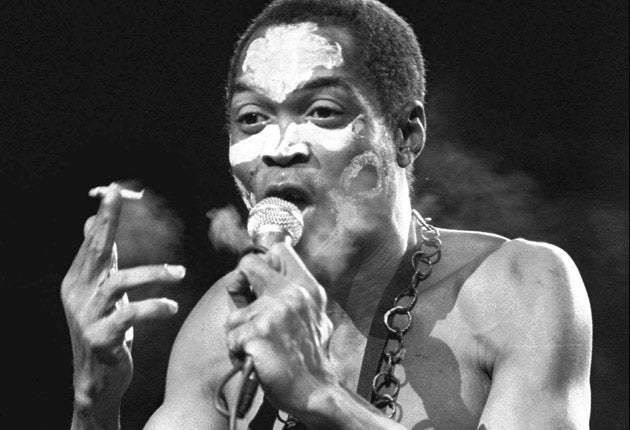

Yorke is as safe as his music. For others, however, protest proved downright dangerous, even fatal. Fela Kuti, delightfully described as "part Huey Newton, part Hugh Hefner", was radicalised by the disproportionate response of the Nigerian military to his high living. Elsewhere, as his beliefs grew unfashionable, Phil Ochs, once Dylan's match, became suicidal, while Chilean singer-songwriter, Victor Jara, was martyred by Pinochet's thugs.

All chose to stand for something. Others were less comfortable with responsibility. Even as millions marched, and writers and actors happily expressed their disgust, Damon Albarn and Massive Attack's Robert Del Naja couldn't find any musicians of similar status to oppose Blair's Gulf War.

Some of Lynskey's omissions grate. The Smiths, underdog friendly, avowedly republican and militantly vegetarian, barely register. Heaven 17's witty attempts at satirising consumerism are absent too, although their daft classic "(We Don't Need) This Fascist Groove Thang" appears in the appendix, one of 100 songs overlooked owing to space considerations.

The best protest music is essentially teenage, and often more exciting than coherent. The virtues we desire in a politician, such as consistency, honesty and compassion, are not valued in a performer – which leaves Billy Bragg scuppered. Maybe as a society we just don't care enough about music. Kanye West is more famous for his unguarded post-Katrina remark – "George Bush doesn't care about black people" – than his records. Gang of Four's post-punk anti-consumerist critique "Natural's Not in It" now soundtracks a Microsoft ad. Unsurprisingly, Lynskey struggles to justify the continued validity of the form. From Middle East to middle England, protests continue, but no one's singing anymore.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments