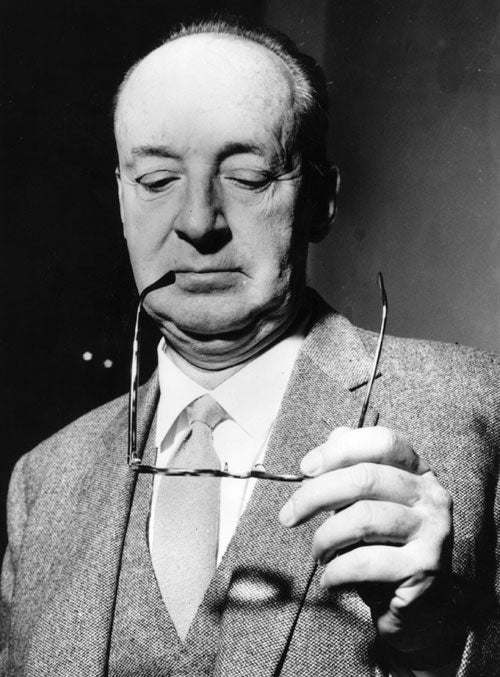

Vladimir Nabokov's unpublished love letters are released

Though he and his wife, Vera, were rarely apart, the author wrote to her for more than 50 years

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Over half a century's worth of love letters from the novelist Vladimir Nabokov to his wife, Vera, reveal a new side to one of the 20th century's best-loved authors. More than 300 letters have been collected by the Nabokovs' son, Dmitry, and are to be published in English next year. A selection of the letters appeared last week, in their original Russian, in the Russian magazine Snob.

The letters span the romance between Nabokov and Vera Slonim, later Vera Nabokov, from their meeting in Berlin in 1923, up until just before the author's death in Montreux, Switzerland, in 1977.

Nabokov devoted most of his published works to his wife, who was also his editor and translator, and the couple rarely separated for any length of time. Nevertheless, their only son discovered more than 300 letters in his mother's archive. She had destroyed her letters to her husband.

Nabokov met Vera at a charity ball in Berlin, and the earlier letters are wildly passionate. "How can I explain to you, my joy, my golden one, my heavenly happiness, just how much I am fully yours – with all of my memories, my poems, impulses and inner tremors?" writes Nabokov shortly after meeting her. "Explain to you that I can't... recall the most insignificant incident without regret – such painful regret! – that we did not go through it together... – do you understand, my joy?"

Born into an aristocratic family in St Petersburg in 1899, Nabokov spent his childhood in Russia. When the Bolshevik revolution came in 1917, the family fled and he enrolled at Trinity College, Cambridge, to study languages. After graduating he settled in Berlin, home to a large community of Russian emigrés, and began his writing career. His earlier books were written in Russian, whereas later novels, including the masterpiece Lolita, were written in English.

"The letters are very recognisably written in Nabokov's style," says Sergey Nikolayevich, deputy editor-in-chief of Snob magazine. "They can't be compared to anything else in the culture of letters; they are part of the heritage of a great poet and writer."

The letters include musings on various themes. "Heavenly paradise, probably, is rather boring, and there's so much fluffy Seraphic eiderdown there that smoking is banned," writes the author in one: "... mind you, sometimes the angels smoke, hiding it with their sleeves, and when the archangel comes, they throw the cigarettes away: that's when you get shooting stars."

During the 1940s and 1950s when Nabokov lived in the US, the letters often contain descriptions of journeys that bear remarkable similarity to the road trip in Lolita, where Humbert Humbert takes the underage girl he loves from motel to motel. "We begin to see where the ideas for Lolita came from," says Mr Nikolayevich.

The later letters, though written with feeling, tend to be devoted to more prosaic matters – how he likes his eggs cooked and the price of milk.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments