The Hobbit at 80: What were JRR Tolkien's inspirations behind his first fantasy tale of Middle Earth?

George Allen & Unwin published the Oxford academic's beloved book exactly 80 years ago today

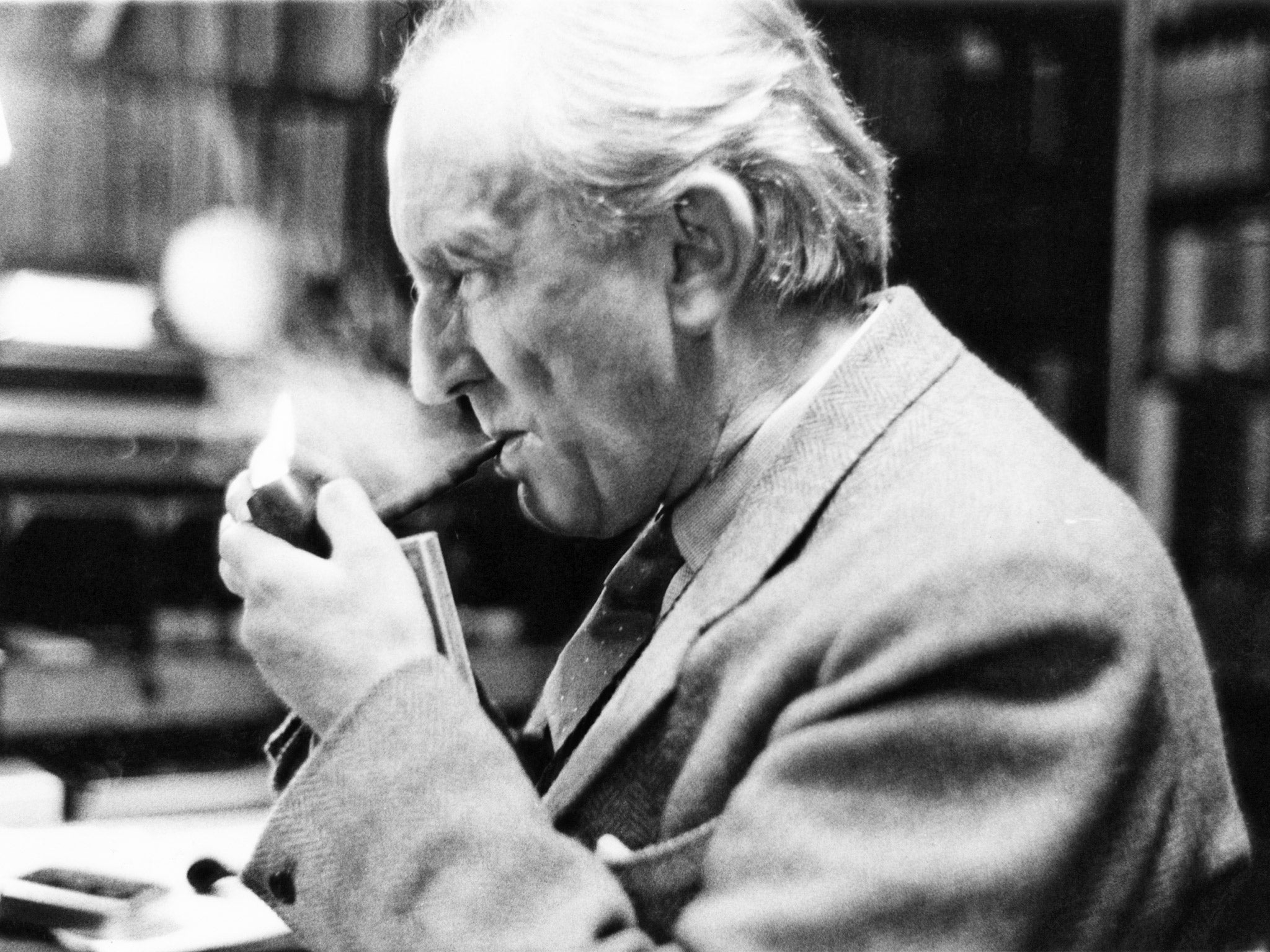

Today marks the 80th anniversary of the publication of JRR Tolkien’s classic fantasy novel The Hobbit, or There and Back Again. This literary institution was born when the Oxford don (1892-1973) had grown bored of marking students’ coursework in his study one evening and reached instead for a blank sheet of paper, idly jotting down a sentence that would become the book's famous opening line: “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit."

From this simple starting point, Tolkien spun the epic tale of Bilbo Baggins’ unexpected journey to the Lonely Mountain in pursuit of treasure, completing the work in 1932 and presenting a draft to a number of his eminent colleagues for inspection.

One of these was CS Lewis, whose own Chronicles of Narnia (1950-56) would likewise cast its innocent protagonists into a fight between the forces of good and evil in a magical realm and share Tolkien’s deeply felt Christian sentiments. The men were close friends and fellow members of the exclusive Inklings club, a group known to meet at the Eagle and Child pub in St Giles every Tuesday during term-time to discuss literary matters.

Tolkien had also presented a copy of his manuscript to one of his students, Elaine Griffiths, who in turn showed it to Susan Dagnall, a friend then working for publishers George Allen & Unwin. Dagnall tipped off her boss, Stanley Unwin, who decided to go ahead and print the novel on 21 September 1937 after rave reviews from his young son. The Hobbit has never been out of print since.

Tolkien’s story and its sequel The Lord of the Rings (1954-55) have delighted children and adults of all ages for eight decades now, their popularity only growing with the turn of the millennium thanks to Peter Jackson’s three-film adaptations of both books, The Hobbit cycle filmed more recently (2012-14) and starring Martin Freeman, Ian McKellen and Richard Armitage.

The academic drew on his extensive knowledge of European pagan and pre-Christian folklore, myths and fairy tales for inspiration. As Oxford’s Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon between 1925 and 1945, Tolkien amused himself by writing narrative poems on fantastical themes and inventing Elvish runic languages from scratch.

The Hobbit’s character and place names are derived from Icelandic linguistic traditions and echo those given in Old Norse sagas such as the Poetic Edda and Prose Edda. The cunning dragon Smaug has been compared to that in the Old English legend of Beowulf (by way of William Morris), a text Tolkien lectured on during his tenure at Pembroke College, while Thorin Okenshield's battalion of dwarves have been likened to those described by the Brothers Grimm.

The writer also borrowed from Victorian genre fiction, developing ideas first proffered in such works as Jules Verne's Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1862), The Princess and the Goblin (1872) by George MacDonald and Samuel Rutherford Crockett's The Black Douglas (1899).

Gollum's gold ring enchanted with a corrupting curse appears to stem from an anecdote Tolkien was regaled with during a visit to an archaeological dig in Gloucestershire in 1929 about the discovery of just such a relic in 1785 in a field once home to a Roman temple.

Although staunchly resistant to interpretative or allegorical readings of his work, JRR Tolkien's memories of his childhood in Sarehole near Birmingham provided the basis for Bilbo's verdant homeland of The Shire by his own admission. A rural idyll where the hobbits live a parochial life of leisure shielded from the dark ambitions of Middle Earth, The Shire is often regarded as an idealised vision of a pre-industrial (and thus, in Tolkien's eyes, prelapsarian) England. Tolkien himself told his publishers his depiction was "more or less a Warwickshire village of about the period of Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee [1897]."

Other locations in both The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings were inspired by real places the author had visited: Rohan and Gondor by the Malvern Hills and their ties to the ancient kingdom of Mercia; Rivendell by a holiday the young Tolkien took to the Swiss Alps in 1911; and the Two Towers by Perrett's Folly and the Waterworks Tower in Edgbaston.

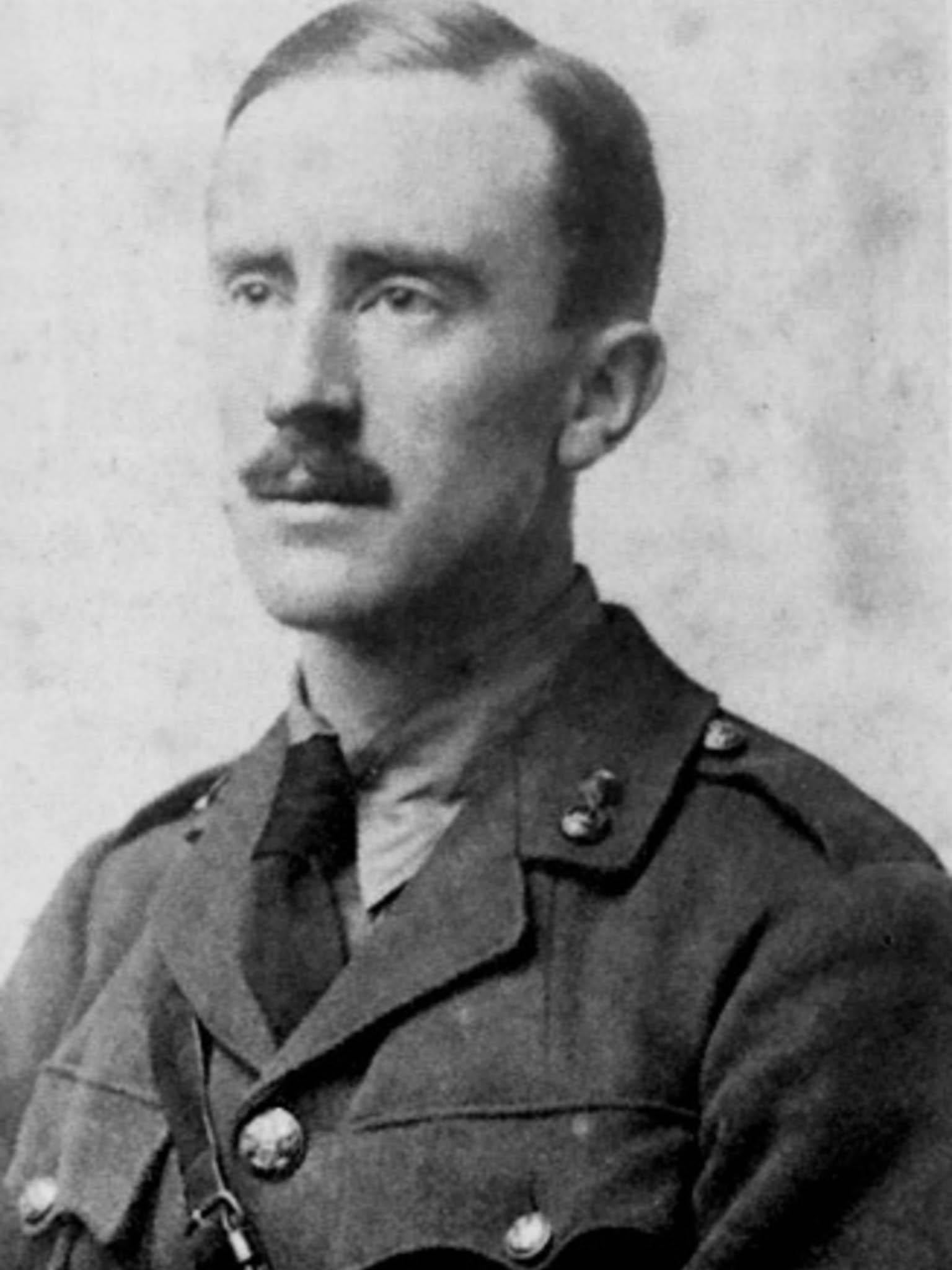

The Hobbit's climactic Battle of the Five Armies meanwhile is said to stem from Tolkien’s experiences during the Great War (see also the Dead Marshes and Black Gate of Mordor in Lord of the Rings).

Initially reluctant to serve with the British Army, describing himself as "a young man with too much imagination and little physical courage", Tolkien relented and joined the Lancashire Fusilliers as a second lieutenant in July 1915, dispatched to face the horrors of the Somme a year later. Operating behind the lines at Bouzincourt, he participated in the assaults on the Schwaben Redoubt and the Leipzig Salient before succumbing to trench fever. His illness no doubt saved him sharing the cruel fate of so many of the brave young men he fought alongside and expressed his affinity for.

Though he denied it, Tolkien's first-hand experience of bloody conflict and brutal slaughter in France must surely have informed the camaraderie displayed by his heroes as they descend into battle, prepared to sacrifice their lives for a cause they believe in.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks