Samuel Johnson: Who was he, and why is he so important to the English language?

Today's Google Doodle celebrates a colossus of English literature

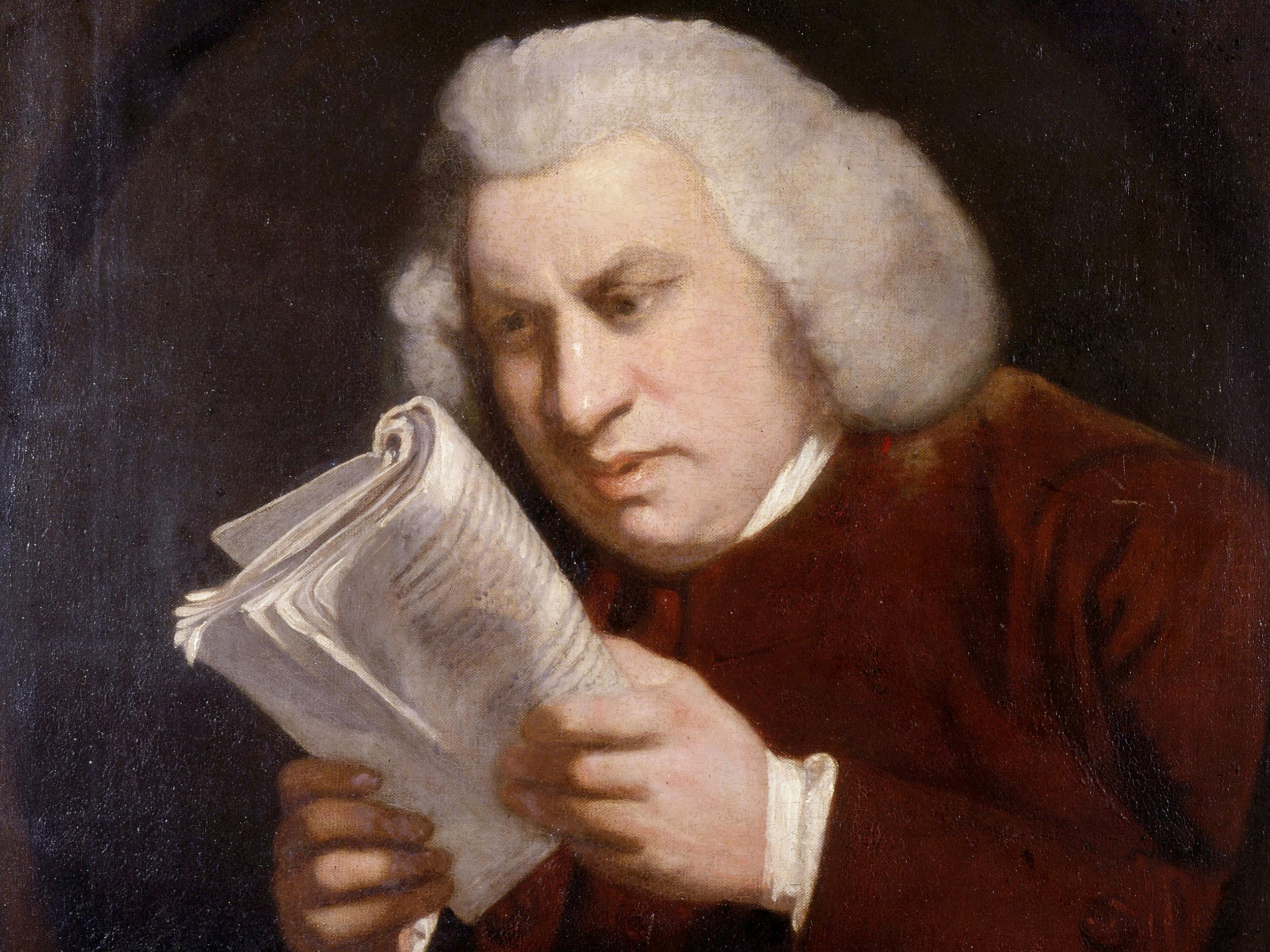

Today’s Google Doodle pays tribute to Dr Samuel Johnson (1709-1784), English wit and author of the Dictionary of the English Language, on the 308th anniversary of his birth.

Johnson’s dictionary appeared in 1755 and remains a landmark achievement of English prose, an extraordinary individual undertaking that included over 42,000 entries and took its writer nine long years to assemble.

But who was Johnson? What else was he known for and why has his legacy endured beyond that of his many illustrious eighteenth century peers?

Samuel Johnson was born in Lichfield, Staffordshire, the son of a bookseller. He attended Prembroke College, Oxford, in his late teens but struggled to afford the fees, complained of the intellectual idleness of his contemporaries and felt humiliated when a fellow student took pity on him and presented him with a replacement pair of shoes as a gift.

The great man left university without completing his degree and launched himself into the coffeehouses and print shops of literary London, living a life of genteel poverty, forever under threat from his creditors. His earliest works included the long-form poems ‘London’ and ‘The Vanity of Human Wishes’ and the periodicals The Rambler and The Idler.

Having completed the mammoth task of assembling the dictionary, a commission for which he was handsomely reimbursed, Johnson wrote an analysis of Shakespeare and a biography of his friend Richard Savage, a poet convicted of murder.

A rare foray into fiction, The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia (1759), followed and proved a commercial success. The novella was an exotic philosophical fable that told the story of a wayward young royal’s decision to leave behind his isolated homeland, the Happy Valley, in search of true contentment in the wider world.

The primary reason for Johnson’s enduring appeal though, outside of his own remarkable achievements in print, is surely the ongoing popularity of James Boswell’s fantastically detailed Life of Samuel Johnson (1791). The book recounts the many wise, comic and vitriolic sayings its subject produced when “talking for victory” late into the night with his peers and clubmates. That circle included such great figures of the age as portrait painter and Royal Academy founder Joshua Reynolds, actor David Garrick, politician Edmund Burke and playwright Oliver Goldsmith.

Boswell recalls such delightful comic incidents as Johnson good-naturedly dismissing Burke as “a vile Whig”, rebuking Goldsmith for being “loose in his principles” and declining a repeat visit backstage to visit Garrick at the theatre because, “the silk stockings and white bosoms of your actresses excite my amorous propensities.” His opinions on everything from remarriage ("the triumph of hope over experience") to women vicars and the merits of Alexander Pope are preserved for the ages in a work whose value cannot be overstated.

Boswell would also document Johnson’s tour of Scotland in his company, while his life was recorded in a separate biography by another friend, the socialite Mrs Hester Thrale, who published her own reminiscences of their time together in 1786.

Today, a statue of Johnson looks out over his former stomping ground of Fleet Street while his name has lived on in the title of a leading prize for non-fiction writing (lately rechristened the Baillie-Gifford), the most recent recipient of which was Philippe Sands.

Modern audiences will no doubt remember Robbie Coltrane’s performance as “the Great Cham” in the BBC sitcom Blackadder The Third (1987) while fans of his famous barbed tongue include stand-up comedian Frank Skinner, who became president of the Dr Johnson Society in 2010.

The good doctor’s namesake, Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson, is another admirer, including him in his 2011 book Johnson’s Life of London and devoting an episode of BBC Radio 4’s Great Lives to his memory.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks