Now for my side of the story: Myerson's son hits back

First his parents banished him because of his drug abuse. Then his mother decided to write about it in her new book. Jerome Taylor reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Two days ago he was portrayed by his Booker Prize-nominated mother as a skunk-smoking degenerate who had to be thrown out of home aged 17.

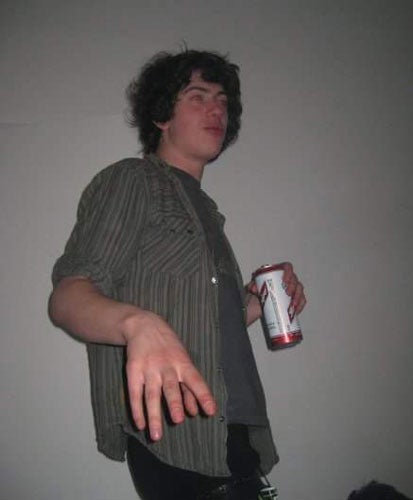

Yesterday, Jake Myerson, the son of the author Julie Myerson and the inspiration for her forthcoming bare-all book, said his parents were "insane" and "naïve" and had led him to live in a squat.

His expulsion from their south London house – he walked up the path to find the locks changed – would have remained a tale little-known outside the circle of friends and family were it not for Myerson's decision to expose the family's struggles with her son's drug use in her latest tome.

She and her husband, the playwright and journalist Jonathan Myerson, were worried that his erratic behaviour and cannabis use were adversely affecting his younger siblings. She describes kicking him out, after he ignored their ultimatums, as "the most traumatic thing that has ever happened to us".

But yesterday, Jake Myerson, now 20, hit back at his mother and her claim that he gave permission for her to publish The Lost Child, out in May.

"Basically, my parents are very naïve and got caught up in the whole US anti-drugs thing," he said. "There is a very big difference between smoking a spliff and being a drug addict. They are very naïve people and slightly insane. They overreacted. They are very emotional people and I refuse to have anything to do with them."

His mother, who rose to fame in 1994 with her semi-autobiographical novel Sleepwalking, claimed in an interview with The Bookseller that her son read a manuscript and was generous enough to understand her need to write about the trauma. But Jake Myerson yesterday insisted he had told his mother that he didn't want the book published.

He told The Independent: "My mother seems to have suggested that I somehow agreed to this book which isn't really correct. The book contains some poetry that I wrote when I was about 15 or 16 and I remember getting a call from my mother saying she'd pay

me £1,000 if she could use it. I was scrabbling around for money at the time so of course I took it but that doesn't mean I wanted it to be published."

Mr Myerson, who lived in a squat after he was thrown out and has since moved to Camberwell, south London, admitted smoking cannabis but questioned whether his behaviour and drug use was all that unusual.

"I am a very changed character who is a lot different to what I was three years ago. I have a completely different lifestyle. But I still maintain that what I was doing at that age wasn't in anyway different from what 40 per cent of teenagers are up to."

He expressed discomfort at the fact that his mother has frequently talked about him in her work. "This book is simply an extension of her maternal journalism. My mother has been writing about me for the past 16 years."

Myerson initially intended for The Lost Child to be about Mary Yelloly, a girl who died of tuberculosis in the 1820s, leaving behind an astonishing collection of watercolours. But the erratic and allegedly violent behaviour of her son while she was writing the book meant it became increasingly autobiographical.

Myerson claims that her eldest son, who was not directly named in the book, went from being a "bright, sweet, good-humoured boy" to a cannabis addict in a matter of months and would propel his family into daily chaos. After refusing to change his behaviour, the Myersons say they had to change the locks and throw him out.

"This thing just came and hit us, almost out of nowhere," she said in an interview last month. "If someone had told us years ago that we would be in that position, it would be unthinkable." Explaining why she decided to make her family's difficulties public, Myerson said: "People need to know this happens to families like ours. We were very smug, we loved having young children and as they got older we thought we were going to be very good parents."

Yesterday, she issued a statement through her publisher, pleading: "Julie hopes people will refrain from making any judgements until they have read the book, from which they will see she loves her son very much."

Mr Myerson began acting erratically while his mother was writing her previous novel, Out of Breath. One of the main characters is a 15-year-old boy called Sam who goes off the rails, to the horror of his younger sister.

The Myersons' concerns about cannabis use among their children reflects a wider debate on whether Britain has become comfortable with turning a blind eye to the potential mental health problems that long-term cannabis abuse can cause.

Politicians and health officials are increasingly concerned about the amount of cannabis abuse in Britain, particularly given the strength of the average bag of hash has increased.

In 1997, about 1,700 people were being treated for cannabis addiction. Today, about 22,000 people are "addicted", almost half of them aged under 18.

Medical researchers say widespread teenage use of the stronger cannabis variant, skunk, is a mental timebomb.

It is grown to yield a high amount of tetrahydrocannabidinol (THC) – a psycho-active compound that disrupts brain activity and provides a more hallucinogenic high. Experts believe that a joint made with the kind of skunk found readily in Britain today contains 10 to 20 times more THC than the average joint from the 1970s.

In January, ministers reclassified cannabis as a class B drug.

Parental battles: Washing dirty linen in public

*David Helfgott

An autobiographical film about the concert pianist's long struggle with schizophrenia upset some members of his family, who claimed it unfairly portrayed Helfgott's father as an overbearing and abusive tyrant. Helfgott was a major contributor to the film, Shine, and described years of abuse by his father, who felt his child could not conquer the notoriously difficult works of Rachmaninov.

*Gayle Sanders

In January, the publishers Hodder and Stoughton had to pay £5,000 damages to 68-year-old Thomas Sanders over a misery memoir that his daughter Gayle had written. The memoir, Mummy's Witness, sold more than 38,000 copies but it had to be withdrawn from sale after Mr Sanders took successful legal action against his daughter, who had accused him of being violent and abusive.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments