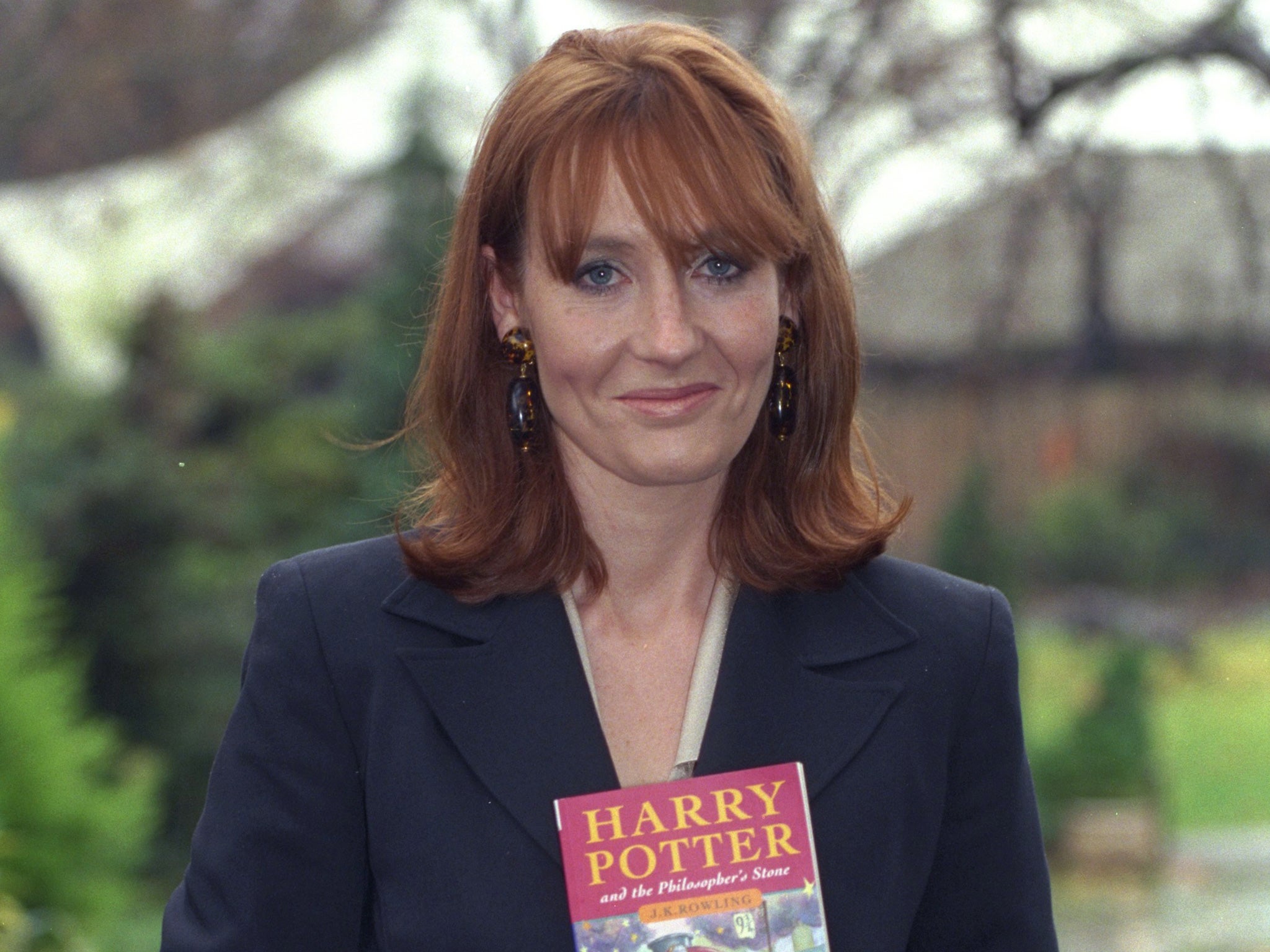

Rude rejection letters could cost you the next JK Rowling or George Orwell, publishers warned

There are countless tales of writerly brilliance being turned away from publishers with a snooty dismissal

JK Rowling was advised not to quit her day job, George Orwell was informed there was “no market” for animal stories and Rudyard Kipling was told he clearly did not understand the English language.

There are countless such tales of writerly brilliance being turned away with a snooty dismissal. But in an age when it is increasingly easy to self-publish, whether online or in print, one publishing house has warned others to think again before sending rude rejection letters, for the sake of future profits.

September Publishing founder Hannah MacDonald said the industry should be more constructive with its criticism and rebuffs, as there is a danger that potential stars might abandon their dreams. “The publishing industry has always been hugely selective,” she told The Independent. “Getting your book published is notoriously difficult. We need to reach out and nurture talent. Publishers could do more to help writers.

“There is nothing wrong with self-publishing and it has helped a lot of authors. But there is a risk of driving people away.”

Self-publishing is not new – Marcel Proust opted to pay for the print run of Remembrance of Things Past himself.

Ms MacDonald raised her concerns at the FutureBook conference last week, saying editors should be given more time by the industry to provide authors with feedback.

“It is very difficult now for agents and editors to find time to reject constructively, and if we can’t communicate with the authors of the future, then they will abandon the industry and become self-publishing authors,” she said, speaking on a panel titled Writing the future: author-centric publishing.

She describes her firm as “author-centric”, with a focus on fostering new writers and working with them to produce books that appeal to readers. She encouraged the industry not to present itself as a “closed fortress” and to be more inclusive. There is also a need to diversify, she added. “We need to appeal to the next generation of writers – to appeal to more cultures, ages, and readerships.”

A rejection is still a rejection, even when it is polite. Had a friendlier approach been adopted in the time of William Golding, winner of the 1983 Nobel Prize in Literature, his allegorical novel Lord of the Flies might still have suffered 20 refusals before becoming one of the defining books of his time. Perhaps James Joyce would still have been knocked back 22 times for Dubliners.

However, the American novelist Louisa May Alcott certainly wouldn’t have been told to “stick to teaching” following her submission of Little Women.

Salt Publishing director Chris Hamilton-Emery agrees with Ms MacDonald. His indie set-up receives about 60 manuscripts a month and puts out only 24 new books a year, but he believes that today’s smaller publishers, in particular, have a duty to writers.

“It is better for writers to have the industry supporting them. You need as many people around you as possible,” he said. “We can’t publish every book and it’s not always possible to give everyone a lot of time. But we don’t have to sweepingly turn writers away. We must nurture them and help them if we can.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks