Fifty years on, Alan Garner concludes Weirdstone trilogy

Professor Colin Whisterfield, now a deeply troubled astrophysicist at the nearby Jodrell Bank radio telescope observatory, combs the cosmos looking for Susan, who disappeared at the end of "The Moon of Gomrath".

With no memory of Susan's disappearance or indeed of anything before he was 13, Colin visits a psychiatrist, Meg, who tries to help him uncover his lost secrets.

The modern story is intertwined with that of The Watcher, a mysterious pre-historic man, who must find "the woman" to prevent the world from ending.

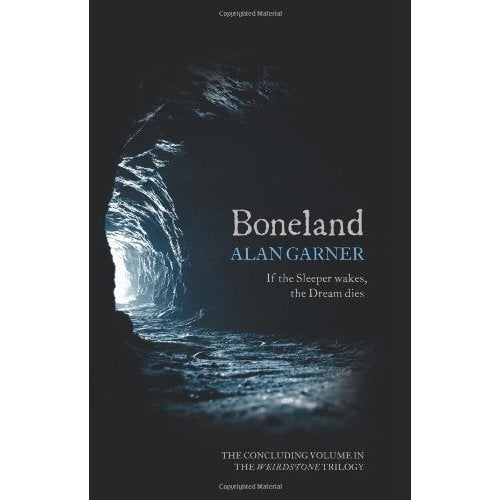

"Boneland" is described as a novel for adults, though magic is in the air. It is published in the UK 30 August by Fourth Estate.

Alan Garner, 77, answered questions about the conclusion to his Weirdstone trilogy, which has taken 50 years to complete, via email:

Q. Why have you decided to return to the Colin and Susan characters after almost 50 years?

A. I never "decide". Nor do I consciously go looking for stories. It feels as though they come looking for me.

Q. Had you always planned to write a third book in the Weirdstone series?

A. I considered it, after "The Weirdstone of Brisingamen", because there was so much interesting research material unused, but by the time I finished "The Moon of Gomrath", in 1962, I couldn't face spending any more years with Colin and Susan. I'd begun in 1956 and had moved on. They hadn't.

Q. How did the story evolve to the point you wanted to complete the trilogy?

A. In 1996, with the publication of "Strandloper", I met adults that had grown up with the first two books who said that they felt that there was a third book "missing". But I was entangled with "Thursbitch" at the time, and it was 2003 before I was ready to formulate the questions: what happened to Colin and Susan, and where would they be now? It seemed worthwhile to find out.

Q. Myth is an important element in "Boneland". What draws you to myths and what place do they have in the modern world?

A. Myth is essential to humanity, not just to "Boneland". Myth is, at all times, unencumbered Truth. Myth has been integral to me throughout my life, and is the only subject I find worth writing about.

Q. What inspiration do you draw from the country around you?

A. Along with many of the world's cultures, I feel a symbiosis with the land. "We" are the same and inseparable. This sense has been lost where the Industrial Revolution caused the dispersal of communities into cities and political, religious or materialistic pressures brought about mass emigration across the seas. Today it is hard for people to live and work where they and their ancestors were born. The severance leads to alienation. I was fortunate in not having to experience that.

Q. Although many of your earlier books are read by children, adults also enjoy them. Had you always intended to target both children and adults?

A. I never "target". I write the story as it comes, for its own sake, no other. Who reads it is beyond my control.

Q. How do you approach planning and writing a novel?

A. I don't plan. Images appear, unbidden, which suggest areas of research. The research develops its own pattern, and when there's no more research to be done I "soak and wait", as Arthur Koestler expressed it. Then, subjectively, the story starts of its own accord, and I write as it unfolds. But it's probably complete in my unconscious, as a result of the soaking and the waiting, before I can be aware of what's happening. This could explain why I get the last sentence or paragraph of the book before I know what the story is. The history of creativity is littered with examples of the artist, or scientist, or mathematician "seeing" the answer and then having to spend years in discovering the question.

Q. What was the focus of your research for Boneland?

A. The universal myth of The Sleeping Hero.

Q. Do you write every day?

A. No. I can't force words to come. They have to gestate. When they are full term, they appear.

Q. Can you say anything about your next project?

A. No, except that it's there.

Q. What fiction excites you at the moment?

A. I don't read fiction.

Q. Do you read e-books?

A. Not yet.

Q. How do you feel about your own work being made available in e-book format?

A. In principle, I have no objection. But whereas an e-book is simply the text and nothing more, to hold a physical book, the product of many skills, is a complex experience, involving touch and smell and memory. I value the fact that there are books in my library that have passed through other hands, been read by other eyes, spanning more than 400 years; and they still work. I can't imagine a reader being able to form a personal relationship with an e-book.

Reuters

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments