Children's picture books 'have lost the plot'

As sales fall by £3m, their first drop in a decade, publishers and bookshops want to play it safe with tried-and-trusted classics

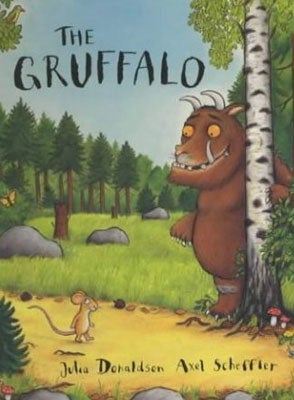

Once upon a time, picture books made publishers very happy. They inspired and delighted millions of children around the world to love books long before they could actually read them. But now they are under threat. From Kate Greenaway's delicate 19th-century watercolours of children in smocks to Julia Donaldson's Gruffalo, Britain's reputation as a market leader for these elaborately illustrated creations is in peril.

Sales of picture books fell for the first time in almost a decade last year, by £3m, about 8 per cent on the figure for 2006, according to market research firm Nielsen. And soaring costs to produce the frequently lavish, hard-back books led to some 500,000 fewer books being produced. Authors and illustrators are now warning of publishers' growing reluctance to take a chance on new talent.

So worrying is the situation that the national reading charity Booktrust has launched a campaign to promote picture books and illustrators to new audiences, as well as to celebrate emerging illustrators.

Helen Mackenzie Smith, the editorial director for picture books at Random House, sad she became a steering committee member of the campaign because she was worried about the "classics of the future" after glancing down the bestseller lists and still seeing such perennials as Where the Wild Things Are and The Very Hungry Caterpillar at the top.

"I wondered what this list will look like in 50 years' time. We'll be in trouble if we don't start encouraging and nurturing new talent now," she said.

Caroline Horn, children's news editor at The Bookseller, said she lists Emily Gravett, Oliver Jeffers, Neal Layton and Mini Grey as among the emerging talent readers might expect to enjoy. "If you speak to authors and illustrators, things are tough for them because it is often only the big names that are stocked in any sort of quantity by major retailers like Waterstones. Also, UK consumers will buy only paperbacks, and publishers need hardback sales to offset the costs of production."

Marc Lambert, chief executive of the Scottish Book Trust, said high costs and staying safe were having a big impact on publishing picture books. "There are lots of economic reasons why retail outlets only stock the top-range picture books. We know that Julia Donaldson is going to sell a shed-load of books, so why would we give up the space to buy her books as against a lesser-known title?" he said.

Michael Rosen, the children's laureate, believes it's not just the publishers who are to blame but the Government too, and parents have a big part to play in any revival. "There is a national anxiety about reading, which is fostered by the Government, which is quite happy to spend large amounts of time, money and effort on the teaching of synthetic phonics and yet not match that with a similar amount time, money and effort in supporting the reading of books," he said.

"There has to be a whole-school approach to reading and enjoyment of books which must include parents. We must find ways in which parents can enjoy books with children. It must be as much a part of the education process as doing science or history."

Not everyone is quite so gloomy about the market, however. Ann-Janine Murtagh of HarperCollins is about to publish in the UK the Fancy Nancy picture book series that has proved popular in the US. She said: "We all need to look out for what is going to be the next big picture book – all it takes is one phenomenon to reinvent the category."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks