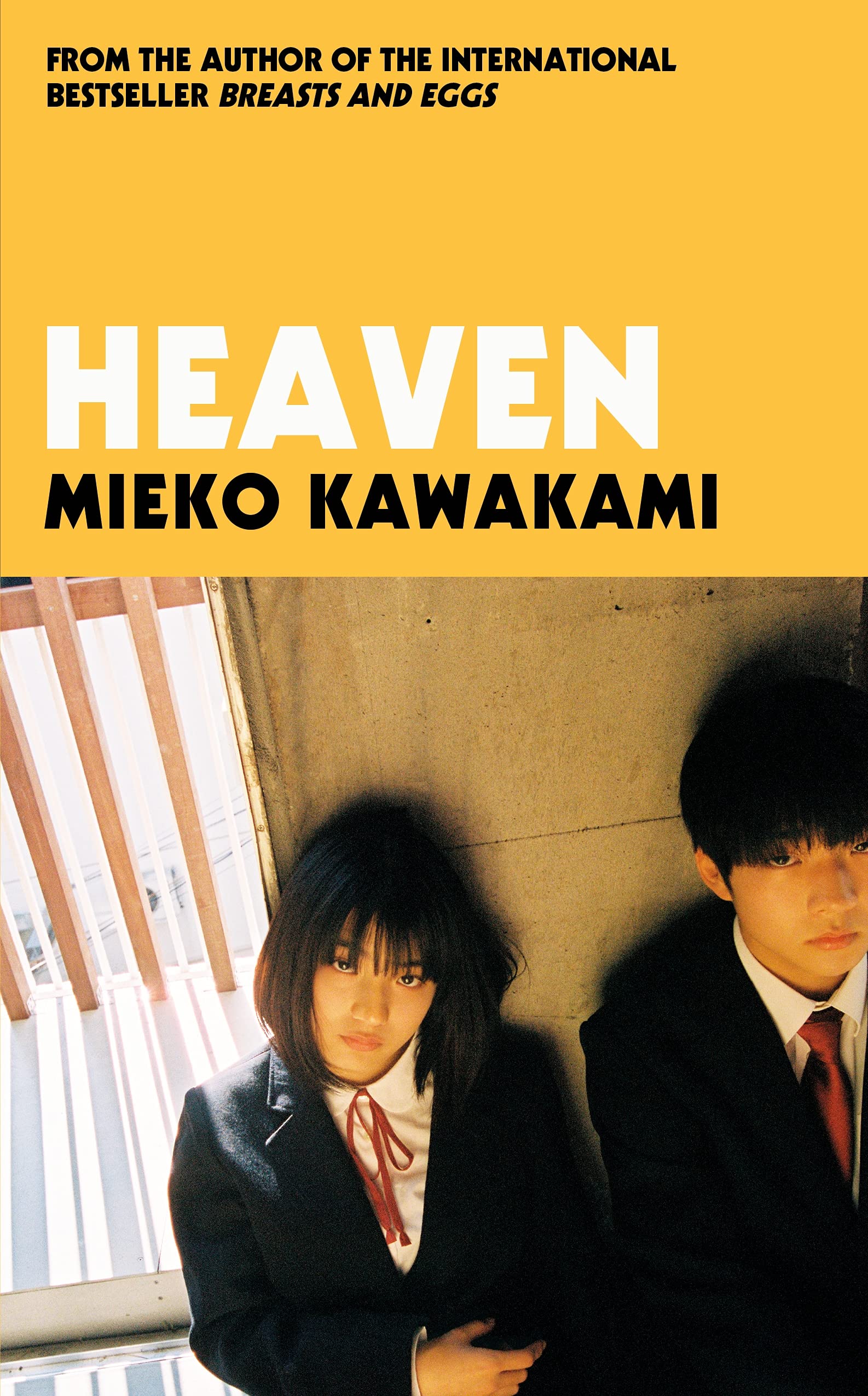

Mieko Kawakami’s Heaven - review: ‘an unrelenting horror film of one boy’s youth’

0Thu-Huong Ha rates Kawakami’s book, full of moments ‘brim with a painful tension’, follows a bullied boy searching for meaning

Mieko Kawakami’s new novel delivers a familiar moment: that scene in the film where the police are just about to rescue the innocents from the villains. “Hang on, help is on the way,” you plead to the screen. Maybe the cops get all the way to the front door, but then they’re led astray. Your heart sinks; deliverance may never come. To read Heaven, by the author of Breasts and Eggs, and newly translated into English from Japanese by Sam Bett and David Boyd, is to bear witness to an unrelenting horror film of one boy’s youth.

The 14-year-old unnamed narrator in Heaven is bullied by sadistic classmates, who make fun of his lazy eye. In the park one afternoon, he sees some sand-covered animal faeces and imagines being force-fed the clumps by his tormentors. The scene initially reads as gratuitous and cartoonish, but we quickly adapt to the narrator’s waking nightmare. By the end of the novel, his paranoia from the park is almost jejune compared to what’s in store for him.

The narrator’s dim days brighten when he starts exchanging letters with Kojima, a girl in his class who’s bullied for her clothes and poor hygiene. The friendless teens forge a secret bond. One day, they take a trip to an art museum to see a painting Kojima has renamed Heaven. The evocation of paradise lingers through their summer outing, which pulses with life, hope and feeling. But from the very beginning, foreboding looms over the friendship.

Back at school in autumn, the narrator receives his most brutal beating yet. Afterward, a chance encounter with Momose, one of his bullies, sets up the not-so-subtle central philosophical question of the novel. Through lengthy monologues, Kojima and Momose present different justifications for the narrator’s pain.

The evocation of paradise lingers through their summer outing, which pulses with life, hope and feeling

Kojima offers a kind of religious, moralistic view, saying that, by allowing the beatings to happen, their physical suffering has worth. “Weakness matters,” Kojima says. “There’s meaning in overcoming pain and suffering.” Momose, though, is nihilistic, telling the narrator, “The weak can’t handle reality. They can’t deal with the pain or sadness, let alone the obvious fact that nothing in life actually has any meaning.” For Momose, the bullying has neither meaningful motivations nor outcomes. Some people simply hurt others because they can, he says casually. And others simply don’t have the will to fight back.

The torture porn in the book, reminiscent of novels such as Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life, trap the reader, and even moments of tenderness between Kojima and the narrator brim with a painful tension. This makes reading Heaven feel like there’s a beautiful, cruel teenage boy sitting on your chest, carelessly tossing his perfect hair while you are slowly suffocated by your own helplessness. In this horror film, oblivious authority figures walk on by as you grope for breath, wondering what it even means to be alive and free. We fear it’s as Momose says: “If there’s a hell, we’re in it. And if there’s a heaven, we’re already there. This is it.”

Heaven by Mieko Kawakami; translated by Sam Bett and David Boyd. PanMacmillan £14.99. Out 10 June 2021

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks