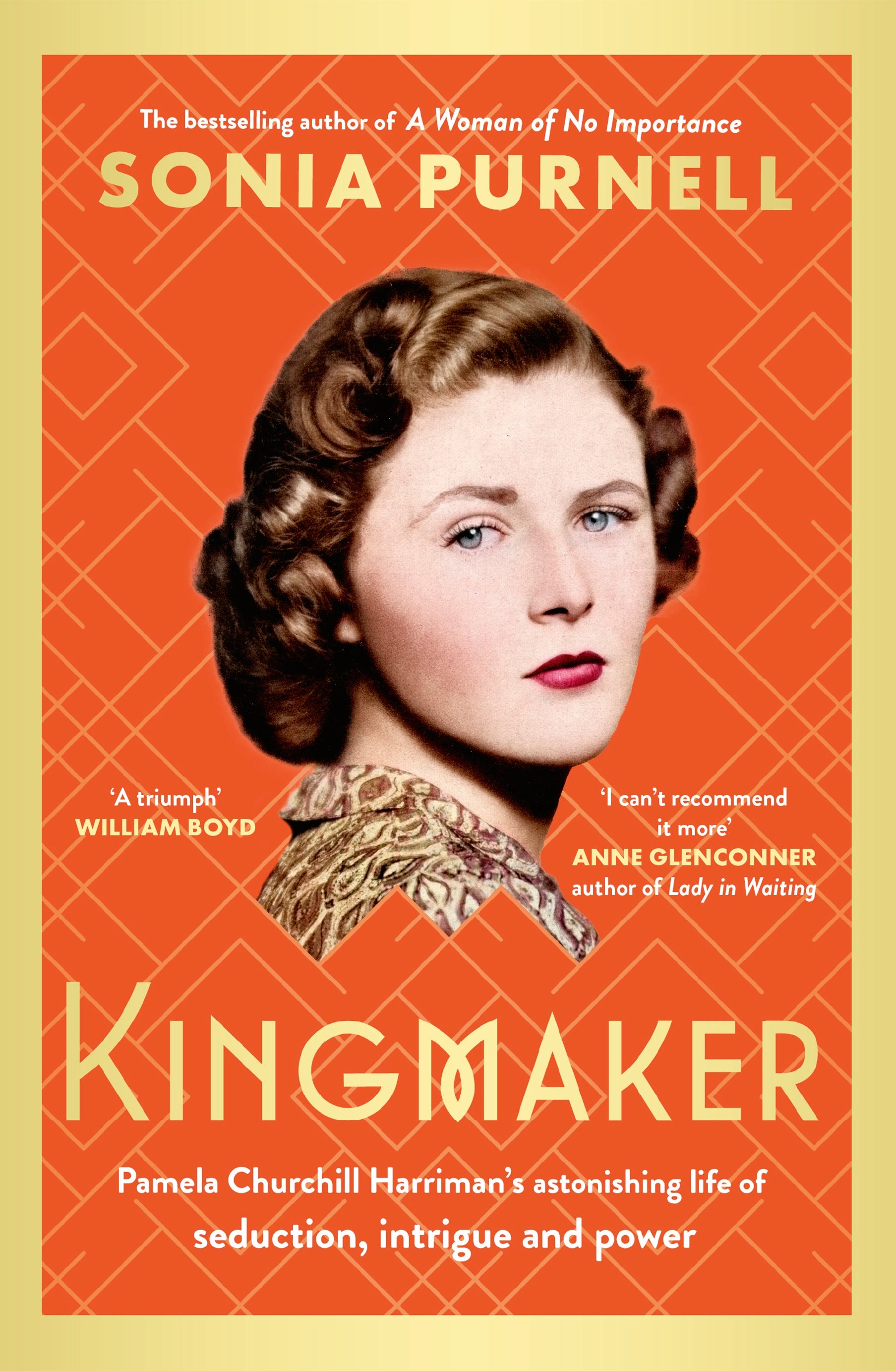

Pamela Harriman was the seductress of the century – from Churchill to Clinton – this is how she did it

Femme fatale Pamela Harriman changed the course of history by captivating leading figures in and out of the bedroom. The ‘kingmaking’ technique she used to devastating effect to lure some of the world’s most powerful men is explained by Sonia Purnell

Pamela Harriman was attending the glitzy White House Correspondents’ dinner in spring 1993 when Barbra Streisand sidled up to her and whispered the question on many women’s lips: just what is your secret? The Hollywood star was 22 years Harriman’s junior but she was as transfixed as any by the British aristocrat’s legendary seductive powers, even as a 73-year-old grandmother.

Pamela gave only a full-throttled laugh in response. She had not become kingmaker of the Democratic Party – credited by the newly elected US president Bill Clinton for his once improbable ascent to the White House – by giving too much away. Only now, more than a quarter of a century after her death and with the release of her private papers as well as fresh testimony from those who knew her, is it clear just how she had succeeded in becoming the legendary “seductress of the century”.

Harriman had been born Pamela Digby, the eldest daughter of a minor Dorsetshire peer and raised to marry another local lord and lead a quiet country life. Like many girls of her class and generation, she had been denied a formal education but she had a quick, intuitive brain. And so when she had a chance, at the age of 19 in 1939, to enter the world of politics and London society by marrying Winston Churchill’s son Randolph – having known him for only a fortnight – she grabbed it.

Although the marriage was unhappy, the thrill of them being invited to live in Downing Street at the nerve centre of a world war made her look radiant. During those dark days her red hair, bright blue eyes and translucent skin made an impact on everyone she met. Soon she was not only Churchill’s highly cherished confidante, but exulting in the admiration of bevies of other powerful, older men. Although never a classic beauty – and dismissed in her teens as fat and frumpy – she was now seen by the society diarist Henry “Chips” Channon as the “auburn, alluring ... crown princess of England”. Pamela was aware of her newfound smouldering sex appeal and quick to realise its strategic potential.

In search of excitement and purpose, she willingly agreed to provide a very special service for her country. So desperate was the British fight for survival in the Second World War that Churchill was prepared to privilege the national interest over the ruins of Pamela’s marriage to the bumptious Randolph. Her task, she was told, was to seduce key visiting Americans who might be able to persuade a hesitant President Roosevelt and the American people to support a beleaguered Britain in her darkest hour.

Roosevelt’s special envoy, a supremely wealthy but perennially dour Averell Harriman, was her first target. Her techniques would evolve, but her goal remained constant: to make her conquests feel like kings. Underneath Averell’s haughty exterior was a man who had suffered from a disciplinarian father as a child and more recently from a razor-tongued wife who thought him stuffy and dull.

Knowing this, Pamela fixed her large sapphire eyes on his, laughed at his attempts at repartee with her tongue pointed erotically behind her teeth and lightly stroked his forearm as he talked. Pamela’s friends dubbed this her “mating dance”, and Averell was captivated. During a ferocious air raid that night, he peeled off her carefully chosen figure-hugging gold lame dress in the Dorchester Hotel suite as the bombs crashed down on the streets around them. Averell had never found sex so thrilling, noting later that there was “nothing like the Blitz to get things going”.

Soon they were sharing pillow talk that Pamela passed back to Downing Street as vital intelligence for the war effort and, under her influence, Averell became a devoted supporter of Britain.

Pamela’s proximity to power – plus her gift for hunting down champagne and glorious food, even during the deprivations of the war – added to her obvious magnetism. So did her ability to discuss battle strategies with those running or covering the war. One by one, American generals, officials, media tycoons and correspondents fell for her until she had a strategic network of male admirers – and informants. One observer compared her to “honey drawing flies … Every man in London was attracted by her.” Bill Paley, the driving force behind the broadcasting company CBS, simply described her as the “courtesan of the century”.

After the war, and divorce from Randolph Churchill, she became an even more glamorous figure thanks to the decolletée and cinched-in waists of the new look fashions of Christian Dior as well as her insistence on retaining the revered Churchill name. After moving to Paris, she had a maid rinse her hair every day with camomile tea for extra shine, rarely rose before midday and fasted on water with lemon to give her eyes their renowned sparkle.

Pamela added new skills to her sexual repertoire after a fling with the playboy prince Aly Khan, who in his teens had been sent to Cairo by his father for a six-week course in an ancient Arabian sexual technique. Schooled by Khan on how to give and receive maximum pleasure for hours at a time, Pamela went on to practise on dozens of fortunate men.

She knew the effect of enthusiasm but also learned what to do, for instance, with ice cubes, and the sensational results (according to at least one beneficiary) of a woman trained to exercise her inner “Egyptian wave”.

Favourite of her conquests was Gianni Agnelli, the handsome billionaire heir to Italy’s largest corporation, Fiat. Agnelli was accustomed to female attention, but he could not resist Pamela’s magnificent figure and her ostentatiously sexy walk. His envious friends, including those on a superyacht who never forgot her lounging on deck dressed in nothing bar a huge set of diamonds.

She made Agnelli feel like a king, arranging his houses to perfection but also coaching him on how to operate as an equal with world leaders. She was the only woman who was not only sensational in bed but who could connect him with key figures in Washington and London.

She had a way with senators. She did a strokey, strokey of their forearm, saying, ‘I’d love it if you could do...’ and they all promised to do it and came away feeling terrific

Even when they parted after four years, the eternally grateful Agnelli called her every morning at seven for the rest of her life. Her next lover, Elie de Rothschild, was enraptured by the trademark mating dance. But her winning move was sending him a silver Cartier cigarette case engraved with a message that their first night together had been the most exciting of her life. He did not know, of course, that she had paid the same compliment to many others.

In the late 1950s, she moved on to America where she met and married Broadway producer Leland Hayward, who had brought The Sound of Music into the world. Beset by self-doubts as his later career began to tank, he revelled in the luxurious home she made for him in a duplex Manhattan apartment – where his every whim was catered for. The revelation that Leland referred to his wife (rather disrespectfully) as La Bouche spread like wildfire in the men’s clubs of New York. “She has,” he boasted, “the best mouth on either side of the Atlantic.”

When Leland died in 1971, Pamela was more desperate than ever for a return to the political game, even if now in her adopted homeland of America, and set her sights on the newly widowed Averell Harriman. Not long afterwards, a friend discovered her in flagrante with the delighted 89-year-old elder statesman, her lipstick smeared all over his white shirt. Shortly afterwards he became her third husband and introduced her to Democratic Party leaders.

Now happily married, she was no longer in the business of physical conquest but nevertheless knew how to marshal her skills as a seductress to persuade politicians to do her bidding. “She had this way with the senators,” recalled Sven Erik Holmes, her one-time chief of staff. “She did a strokey, strokey of their forearm, saying, ‘I’d love it if you could do...’ and they all promised to do it and came away feeling terrific.”

Later, after Averell also died, Pamela took several younger men as lovers and enchanted many more. A legendary face-lift took years off her and by wearing diamond earrings she added luminescence to her skin. When Clinton appointed her the first female American ambassador to Paris shortly after her encounter with Streisand, Paris Match marked her arrival in the city of love by celebrating how she had “turned the scandal of her past into an ornament”.

The president was thrilled with how she helped to reverse years of Franco-American distrust with her personal brand of diplomacy. Although now in her seventies, soon Paris was awash with rumours about her love life. Even the happily married Antony Beevor, little more than half her age, found himself transfixed by her eyes while sharing a sofa at a Paris dinner party. The Newsweek bureau chief, also in his forties, sat next to her at another dinner and was given the full king treatment. Afterwards, he remarked that “the idea of her as a courtesan made sense that evening. Younger men fell for her all the time.”

Of course, Pamela was strategic in her targets and recruiting an influential journalist to her fan club was hardly accidental. She also enchanted many of his French counterparts with her special technique. One, Bernard-Henri Lévy, recalled “her habit of staring at men, then looking down modestly, the sign of an accomplished seductress”. Apparently, it worked every time.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments