Notting Hill Editions essay competition: Five Ways of Being a Painting

‘Being a painting can make you strange,’ writes William Max Nelson, ‘to yourself and to others. It has long been a means of exploring who we are and how we differ’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.William Max Nelson is a writer and historian born in California and raised in Maryland. He now lives in Canada where he is a professor at the University of Toronto. He has published numerous academic works on the intellectual history of the Enlightenment and the development of early modern globalisation.

Five Ways of Being a Painting

Five ways of being a painting. Only two of them common.

Reflecting on his childhood in Berlin at the turn of the century, Walter Benjamin wrote that he feared being exiled in things. He often felt trapped in objects that absorbed his being. No longer a boy, he was blue and white Chinese porcelain, the bright pigments of a watercolor set, a fluttering white curtain, or a soap bubble floating through a room. Repeatedly, he lost himself.

Benjamin did not only get enveloped in matter and trapped in objects. When looking at photographs and paintings, he often found himself displaced into the picture.

Being a painting can make you strange, to yourself and to others. It has long been a means of exploring who we are and how we differ. Being a painting gives you an existence in both the inverted world and the familiar one. It displaces you through alienation and renewed attention.

It can be used to reveal one person from another, one culture from another. But it also has other functions that draw on the almost occult power of what Benjamin called ‘opaque resemblance’.

At dusk on the dock in La Rochelle, two objects draw me in. A stack of lumber and a pile of goods unloaded from an absent ship.

Men are cutting rough planks out of tree trunks. They stack the planks in a large square pattern that reaches twice their own height. On every other level of the stack, one plank protrudes. Together these protruding ends make a stairway spiralling around the pile, allowing the men to place a portable metal roof on top each night.

The evening light falling on the men is too good. It is light that does not really exist until we call it crepuscular and sublime and idealize it in a painting.

Closer to the water, next to an empty ship berth, goods are stacked, waiting to be moved to a warehouse. There are six large white sacks that would look sublime in their plainness if it were not for the number thirty-one drawn on the side of one of them.

These sacks and the sawyers in La Rochelle are the objects in a painting by Claude-Joseph Vernet completed in 1762 and displayed at the Paris Salon of 1763. Although it is too small to see in most reproductions of this painting of the port, a large Chinese character is written on one of the sacks.

Berlin Childhood around 1900 is one of Benjamin’s small masterpieces. It grew out of notes he took in the early 1930s when he began to fear that he would have to flee into exile in the near future.

The notes became a manuscript that he took with him when he left Germany for the last time in 1933.

In his written account of the Paris Salon of 1767, which effectively inaugurated modern art criticism, Denis Diderot flirted with absorption while describing Vernet’s painting of La Rochelle. He showed readers a way to get lost in Vernet’s work. If one were to view the painting through a looking glass, taking in most of the image while avoiding the borders, one could easily forget that it was a view of a painting.

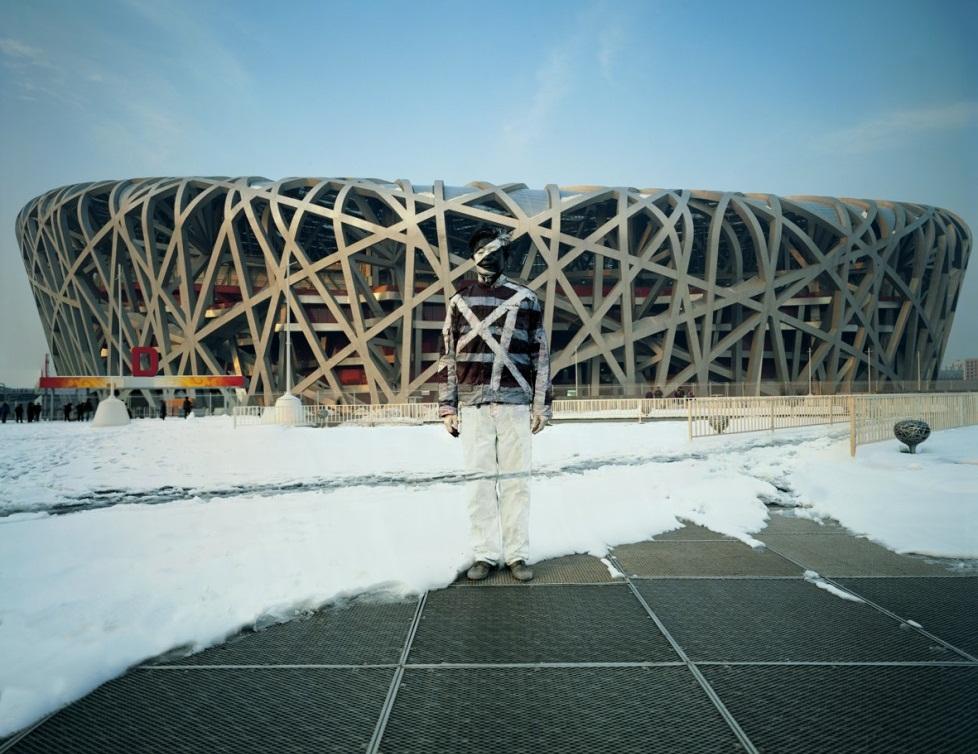

Liu Bolin says that he first painted himself into a landscape in 2005 when the Chinese government demolished an artists’ colony in which he worked. He painted himself to resemble the background scenery with the help of assistants and had them photograph him in front of the wreckage.

Many of his works have an overt political message. They are acts of political estrangement and political commentary. But they are also a special type of present absence. Through a blend of painting and photography, the absence of the artist colony is unconcealed by the presence of the camouflaged Bolin. We are made to see things hiding.

The bourgeois home of Benjamin’s childhood was full of knick-knacks and decorative objects. His favorite object to get lost in was the Chinese porcelain. It was only of export quality, thick and clumsy, but he liked the colors and the texture of the mottled surface.

In the early draft of Berlin Childhood where he mentions this, Benjamin also tells the story of a Chinese painter inviting friends over to his house to view his newest painting. Letting themselves into his house, the friends cannot find the painter, though they see the painting. It depicts a stream and a path running through a park toward a tree-shrouded cottage. They find the painter walking along the path to the cottage, turning and smiling at them before disappearing through the doorway.

Another way of being a painting: being photographed into one.

As a child, Benjamin felt so distorted by similarity to those things that surrounded him that he found it odd to be asked to resemble himself. This challenge was particularly acute when his mother brought him to a photography studio that resembled a mixture of a boudoir and a torture chamber. Put into a costume and posed in front of a painted backdrop, Benjamin did not feel like himself.

For Bolin, being a painting is a way of being himself.

As children, my sister and I were photographed in front of many painted backdrops. Or more accurately, we were photographed in front of many reproductions of photographs of paintings. My mother regularly took us to a photo studio for portraits.

Now, as an adult, I can displace myself into Vernet’s picture of La Rochelle more easily than I can into pictures from my childhood.

Six years after the first mission of French Jesuits arrived in China, the emperor sent one of them, Joachim Bouvet, back to France as his representative tasked with developing relations with the King of France and bringing back artists. In 1698, Bouvet led seven Jesuits, the sculptor and lay brother Charles de Belleville, and the lay painter Giovanni Gherardini to China, departing from La Rochelle.

Benjamin was fascinated by Brecht’s revolutionary theatre. He wrote an essay analyzing and explaining the unusual techniques intended to alienate the audiences, keeping them from becoming too absorbed in the drama. Brecht wanted to cultivate critical thought. He tried to create various theatrical devices to make viewers reflect on what was unfolding around them, not just on stage, but in the wider world. When he wrote his own essay explaining his alienation effects, he used the example of the techniques of classical Chinese acting.

In 1782, the seventy-one-year-old Emperor Qianlong of China reflected on a portrait of himself as a young man. It was a portrait of him painted alongside his father by the Jesuit lay brother Giuseppe Castiglione, who lived in China for more than fifty years and became a favorite of Qianlong’s for the way that he drew on his European training and adapted it to the classical Chinese style.

Qianlong’s adult reflections on the painting became a part of the painting itself. In white characters on the empty blue space of the upper right of the painting, the emperor registered his appreciation of Castiglione’s ability to capture resemblance and his own lack of recognition of his younger self.

There are many ways to separate yourself from yourself. Whether intentional or not, this self-alienation creates the possibility of returning to yourself. Catching yourself being a painting, at least momentarily, is one route with five variations of return.

One.

Being caught photographed in front of a painted backdrop.

Two.

Brushing pigment on yourself, perhaps using the pigment to camouflage yourself within a landscape and then photographing the scene to heighten the strangeness.

Three.

Pulling a painting inside your mind and making the phantom landscape real, then imagining yourself into the scene inside your head.

Four.

Finding that a painting drew your attention and held you until you finally noticed yourself returning to your body outside the painting.

Five.

Most conventionally and strangely, finding yourself captured by pigment in a portrait.

…

The images from my childhood that most absorb me are not paintings or photographs, but films. My parents included a large catalogue of these films (converted to video) on the DVD that they gave to me. The movies are all of everyday moments, mostly sporting events that I participated in throughout my childhood, competitions that were meant to be heightened moments of existence, or at least nervous and charged times of focused attention. Watching the movies, I do seem focused, though the frequency of these events seems to have made me immune to their specialness. Swim team meets. Soccer games. Basketball tournaments. Track meets. I loved all of them and took them completely for granted. The only moments of strangeness that I see when watching them is when I rewind the video and see myself moving in reverse. This was not an experience available to earlier viewers of film, but sitting at my computer I am able to watch long stretches of my childhood soccer games moving backwards, everything moving with a new purpose, like sparks flying back to the source.

My childhood is like an exotic unreal place, like many of Europe’s early images of China. Often, I cannot enter into the picture. At best, through the layers of mediation, I can see my childhood in the way I see Liu Bolin – what I see is something concealed. What I see is not so much a presence, but a present absence, since the mediations obscure it while also allowing me to see it hiding.

Extract from Five Ways of Being a Painting and other essays published by Notting Hill Editions, £14.99. Quote INDY17 to buy the book at the special price of £12.00 from nottinghilleditions.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments