William Shakespeare at 400: Why the First Folio is the greatest single volume of work in English literature

This year marks 400 years since the first publication of Shakespeare’s plays. The ‘First Folio’ was a labour of love and a statement of intent, writes Robert McCrum – and yet, the Bard would express mystified pleasure at the fuss we’ve been making

William Shakespeare would have smiled at this 400th anniversary of his First Folio. He always revelled in the dramatic present. No fewer than three of his plays begin with “Now”. Imminence is his default position, and that’s Elizabethan: from sunrise to sunset, Shakespeare’s age lived in the present moment.

Such immediacy is a constant thread in the tapestry of thought and language that will become a hallmark of Shakespeare’s genius. And yet, paradoxically, for a writer so attuned to the present moment, he’s a tortoise as much as a hare. His literary afterlife is the triumph of the long game: scarcely a hint of celebrity in his own day, and more than a hundred years of neglect and obscurity after his death in 1616.

Authorship in Elizabethan times was not the phenomenon we know today. If Shakespeare had died of the plague before 1600, we’d remember him as a poet. In the celebrations surrounding the quarter-centenary of the First Folio, the greatest single volume in English literature, the most remarkable fact about this literary event would be the playwright’s bemused surprise, even mystified pleasure, at the fuss we’ve been making.

Throughout his career, Shakespeare worked night and day to appeal to the playhouse and gratify his royal patrons. But most of this was achieved below the radar; for much of the 1590s, the author of the box-office smash Titus Andronicus, or successful plays like Richard II, Richard III and Romeo and Juliet (published in quarto editions during 1597), was semi-invisible.

The title pages of these first printings identify the Lord Chamberlain’s Men as performers of the script, but make no reference to any dramatist. In 1598, things change: “Shake-speare” and his fortunes begin to look up. The circulation of his “sugared Sonnets” in court circles had brought his reputation to a tipping point.

In hindsight, the death of Christopher Marlowe is the turning point, and 1593, Shakespeare’s 30th year, a career milestone, with the publication of Venus and Adonis, a word-of-mouth sensation. Before the success of Hamlet, Shakespeare the playwright was renowned at court, but not a celebrity among the public. With widespread illiteracy, such fame was not yet possible. Despite this obscurity, as a poet, Shakespeare toyed with one classical obsession more than any other, the verdict of posterity. “Sonnet 71” playfully inverts this conceit with “Do not so much as my poor name rehearse”.

Then his own extinction loomed. After 1611, the year of The Tempest, life began catching up with art. In his prime, Shakespeare often played the ghost, using the stage direction “Exit Ghost” three times (in Julius Caesar, Hamlet and Macbeth). In As You Like It, he had anticipated this “last scene” of humanity’s “strange eventful history” as “second childishness, and mere oblivion”, in a famous summary of old age: “Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.”

Now the mind and imagination that had driven Shakespeare for years began to betray faint hints of old age. Approaching 50, Shakespeare was conscious of his end game. His own simple summary, in Hamlet, is pre-emptive: “If it be not now, yet it will come.”

Were there, in those final years, any conversations with “sweet Will” Shakespeare about posterity? Or tentative discussions about a “Collected Works”? It is tempting to imagine a visit to the house at New Place in Stratford by John Heminges and Henry Condell, his former fellow actors, with bundles of play scripts, but we’ll never know. Shakespeare sustains his lifelong enigma from beyond the grave. There is, however, one documentary certainty.

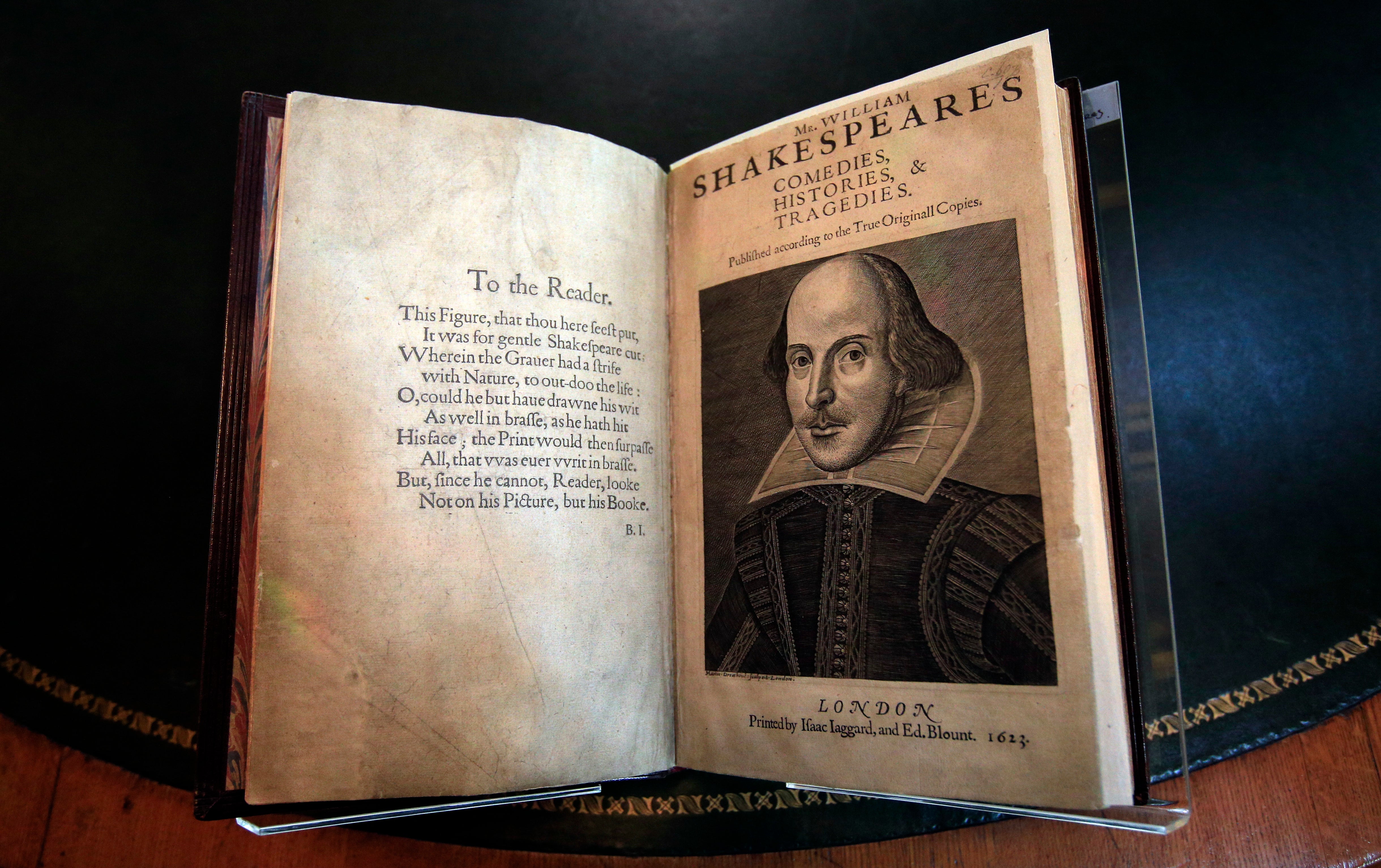

Towards the end of November 1623, the bookseller Edward Blount, who traded at the sign of the Black Bear near St Paul’s, finally held in his hands the text of the massive volume, some 885,000 words, for which, since executing the commission, he had been waiting: Mr William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories & Tragedies Published according to the True Originall Copies.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of the publication of the majestic book – shall we say icon? – known as the First Folio. In dedicating this volume to their patrons, the editors make it clear to posterity that they are in the artistic legacy business: “We have collected [the plays]….. only to keep the memory of so worthy a friend and fellow alive as was our SHAKESPEARE.”

The marmoreal 900-page outcome of whatever was – or was not – discussed between the playwright and his editors, is a labour of love, and a declaration of intent. This authoritative edition of his work established “Shakespeare” for all time, in two principal ways. First, it collected some 36 plays, including 18 scripts (especially Macbeth, Julius Caesar, As You Like It and The Tempest) that would have otherwise remained unknown.

Just as importantly, the First Folio connects Ben Jonson and many of the actors who had first performed these plays with the historical person, the playwright himself, a figure helpfully illustrated by a famous frontispiece, the engraving of the author (compared by some to “a self-satisfied pork butcher”) that’s become the logo for Shakespeare studies.

George Orwell says that, at 50, “everyone has the face he deserves”. The enigmatic Shakespeare has at least six disputed images in search of an author, but only one really matters: the frontispiece to the First Folio executed by Martin Droeshout, the Dutch engraver, who had known Shakespeare.

More than any competing image, this symbol of the playwright’s afterlife has three indisputable characteristics that must be taken seriously despite a fog of speculation. Notably, it comes down to posterity in three separate versions, indicating the care lavished on this likeness by the editors. Second, the Droeshout engraving is contemporary with many of those who had worked with Shakespeare at the Globe. Third, more crucially, this portrait is matched by an encomium to “Shakespeare” the playwright by his great rival, Jonson, expressed with all the swagger for which he was renowned, dominating the opening page of the First Folio.

Jonson had been Shakespeare’s chief competitor during the 1600s, a dramatist convinced of his own importance, and more than slightly obsessed with posterity (a familiar affliction). Garrulous, vain, argumentative, jealous, proud, and deeply committed to exposing hypocrisy and corruption, Jonson was never a man to kowtow to nobility or privilege. Now, without qualification, he announces his rival as “the soul of the age”.

And he goes much further. It is Jonson who declares that Shakespeare is “the applause, the delight, the wonder of our stage”, and then – a few lines later – that he is “not of an age, but for all time” and claims him, with affectionate certainty, as “My gentle Shakespeare….” Here, beyond question, is one literary great paying posthumous tribute to another. In a rational universe, Jonson’s lines would confound any conspiracy that says that “Shakespeare” is just an alias.

Next to the incalculable treasure of the work printed in the First Folio, it’s for Droeshout’s portrait that Shakespeare and his many admirers should be grateful.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks